Skills CFA Contact Centre Labour Market Information

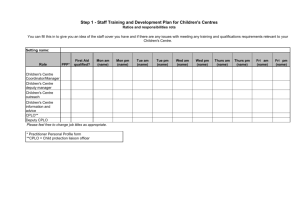

advertisement