Variation in provider identification of obesity by patient

advertisement

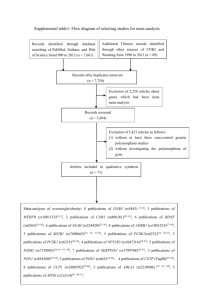

Variation in provider identification of obesity by patientpatient-level and neighborhoodneighborhoodlevel characteristics among an insured population Sara N. Bleich1 Jeanne M. Clark2,3 Suzanne M. Goodwin1 Mary Margaret Huizinga2,3 Jonathan P. Weiner1 1Department of Health Policy and Management, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health of Medicine, Division of General Internal Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine 3Welch Center for Prevention, Epidemiology, and Clinical Research, Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions 2Department Outline Background and Significance Research Objective, Data and Methods Results l Conclusions, Limitations and Policy Implications Background Obesity disproportionately affects minorities and low SES groups Significant racial and SES differences in receipt of health care services Cli i i Clinicians differentially diff i ll diagnose di andd treat obesity Prior studies on practice patterns of obesity care focus on patientpatient-level characteristics Rationale for focus neighborhood characteristics Place of residence matters (Living in low SES or minority neighborhoods associated with an increased likelihood of late--stage cancer diagnosis among Black and Hispanic late women, Barry B et al., l 2005) Individual characteristics insufficient to explain disparities in obesity diagnosis Social Ecological Theory – Individuals are nested within networks Neighborhood context may capture factors that impact obesity diagnosis Availability of resources Physician/nurse supply Health system infrastructure Cultural norms Higher coco-morbidity risk Receipt of appropriate obesity care matters for weight loss efforts Patients told byy their pphysician y that theyy are overweight g are more likely to try to lose weight (Kant et al, 2007) Patients counseled about their weight or weightweight-related behaviors are more likely to report working on those areas (Loureiro (Loureiro et al, al 2006) Patients advised byy their pphysician y to modify y their behavior are generally more confident and motivated to engage in lifestyle modifications ((Kreuter Kreuter et al, 2000) Outline Background and Significance Research Objective, Data and Methods Results l Conclusions, Limitations and Policy Implications Goal of study Objective Objective: j : Identifyy variation in pprovider identification of obesity by patientpatient-level and neighborhoodneighborhood-level characteristics among an insured population Research question: question: Do obese plan members living in minority or low SES communities receive an obesity diagnosis? Hypothesis Hypothesis: yp : Members livingg in lower SES neighborhoods g or neighborhoods with a higher percent of minority residents will have a lower likelihood of receiving an g from their pprovider. obesityy diagnosis Data Blue Cross Blue Shield (BCBS) claims data, data 2002--2005 (three plans) linked to: 2002 Health Risk Assessment (HRA) surveys Member height and weight (self(self-reported) ZIP code level neighborhood characteristics (2000 Census) Included plans covered weight loss medications, nutritional counseling and bariatric surgery during the study period Note: The zip code was based on the member ZIP code of enrollment. Key advantages of data Examination of a population not limited by financial barriers to health care access Largest and most current database that has b been usedd to examine i physician h i i practice i pattern of adult obesity care BCBS is the largest g insurer in the countryy Methods Research Design Cross--sectional analysis of BCBS enrollees Cross Exclusion criteria Enrolled less than 6 months in the year in which their HRA was completed Less than 18 years old or their data was missing Had a pregnancy and/or delivery claim during the study period Had a body mass index (BMI) less than 10 kg/m2 or greater than 100 kg/m2 Missing height or weight needed to calculate their BMI St d sample: Study l 16,151 16 151 obese b plan l members b based b d on self lf 2 reported BMI ≥ 30 kg/m Anal sis Analysis Logistic regression, adjusted for potential clustering of risk factors by neighborhood Outcome measure Obesity diagnosis The International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD (ICD--9) diagnostic codes: 259.9, 278.0, 280.1, 783.1, 783.6, V77.8, V85.0V85.0-V85.54 Covariates Neighborhood-level (zipNeighborhood(zip-code) Patient Patient--level Age Proportion of Black Gender residents Obesity Ob it class l Median household income, class I: BMI 30.0 30.0--34.9 kg/m2 class II: BMI 35.035.0-39.9 kg/m2 adjusted for inflation class III: BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2 Percentage off residents id with ih Co Co--morbidities a high school degree Type 2 diabetes Hypertension yp Percentage living in an Dyslipidemia urban area Number of unique providers seen Note: All patient-level variables were obtained from the claims data with the exception of body mass index. In the models, Census level variables were measured in tertiles. Outline Background and Significance Research Objective, Data and Methods Results l Conclusions, Limitations and Policy Implications Sample characteristics Individual-level SD Age g 48.4 yyears 12.7 Female 48.0% -- Hypertensive 29.2% -- T Type 2 Diabetes Di b t 10 3% 10.3% -- Dyslipidemia 26.8% -- Number of unique provider visits 8.2 9.9 Proportion black residents 5.3% 14.4 Median household income $46,759 $14, 202 High school graduates 70.5% 7.3 Proportion urban 81.7% 28.9 7.7% -- Zip code-level Ob it Diagnosis Obesity Di i Physician identification of obesity Morbidly obese BCBS enrollees more likely to receive i an obesity b i diagnosis di i BMI in obese study sample for persons with and without obesity claim diagnosis; mean BMIdiagnosed 38.4 kg/m2 vs. mean BMIun-diagnosed 34.5 kg/m2, p < 0.001) Patient-level characteristics influence Patientphysician h i i identification id ifi i off obesity b i OR (95% CI) Female 1.48† (1.29, 1.70) Age Age 44 and below 1 64† (1 1.64† (1.42, 42 1.90) 1 90) Age 45 and above 1.00 (reference) Hypertension 1.55† (1.32, 1.81) Type 2 Diabetes 0.98 (0.81, 1.19) Dyslipidemia 1.54† (1.32, 1.80) Obesity class Class III 4.08† (3.46, 4.82) Class II 2.05† (1.76, 2.39) Class I 1 00 (reference) 1.00 Number of unique providers visits in HRA year † Statistically significant at p<0.05 1.20† (1.16, 1.24) Neighborhood-level characteristics influence Neighborhoodphysician h i i identification id ifi i off obesity b i OR (95% CI) Proportion of Black residents Tertile 3 (highest) 0.75† (0.57, 0.98) Tertile 2 0.98 ((0.78,, 1.24)) Tertile 1 (lowest) 1.00 (reference) Median household income Tertile 3 0.94 (0.70, 1.26) Tertile 2 1.07 (0.87, 1.31) Tertile 1 1.00 (reference) ( ) Percent high school graduate Tertile 3 0.95 (0.74, 1.22) Tertile il 2 1.07 (0.87, ( 1.31)) Tertile 1 1.00 (reference) † Statistically significant at p<0.05; The model also controlled for percent urban; result non-significant. Outline Background and Significance Research Objective, Data and Methods Results l Conclusions, Limitations and Policy Implications Conclusions Consistent with national data,, pprovider identification of obesity was low and varied by patient characteristics Neighborhood characteristics (e.g., zip code with a higher concentration of blacks) were moderately important to provider diagnosis of obesity A keyy contribution of this paper p p is the examination of the relationship between neighborhood characteristics and obesity diagnosis, which has received little attention to date Limitations Cross--sectional data Cross Reliance on selfself-reported height and weight Differential member completion of HRA data Physician y obesity y coding g Mismatch between zip code of residence and location of care 2000 Census estimates Lack c of o membermember e be -level eve race ce data d Policy implications and next steps Considerable missed opportunities pp in the diagnosis g of obesity, particularly for members at higher risk and members living in neighborhoods with a higher concentration of blacks More precise measures needed to understand how neighborhood effects disparities in obesity diagnosis A better understanding of these influences may help better target federal efforts aimed at reducing obesity rates and eliminating health disparities Acknowledgements The data and inin-kind database development p support pp and guidance were provided by the BCBS Association, BCBS of Tennessee, BCBS of Hawaii, BCBS of Michigan, g , BCBS of North Carolina,, Highmark, g , Inc. (of ( Pennsylvania), Independence Blue Cross (of Pennsylvania), Wellmark BCBS of Iowa, and Wellmark BCBS of South Dakota Technical assistance with the claims data was provided by Thomas Richards, Richards Andrew Shore Shore, and Hsien Hsien--Yen Chang of Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Contact information Sara Bleich Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Health l h Policy li andd Management sbleich@jhsph.edu 410.502.6604 Appendix Diagnosis g Obesity Hypertension Type 2 Diabetes Dyslipidemia ICD-9 Code 278.0, 280.1, 783.1, 783.6, V77.8, or V85.0V85.54 401-405 250, 250.0, 250.00, 250.02, 250.1, 250.10, 250 12 250 250.12, 250.2, 2 250 250.20, 20 250 250.22, 22 250.3, 250 3 250.30, 250 30 250.32, 250.4, 250.40, 250.42, 250.5, 250.50, 250.52, 250.6, 250.60, 250.62, 250.7, 250.70, 250.72, 250.8, 250.80, 250.82, 250.9, 250.90, 250.92 272 2 – 272.9 272.2 272 9