The Influence of Primary Care Practice Climate on Patient Trust Background

advertisement

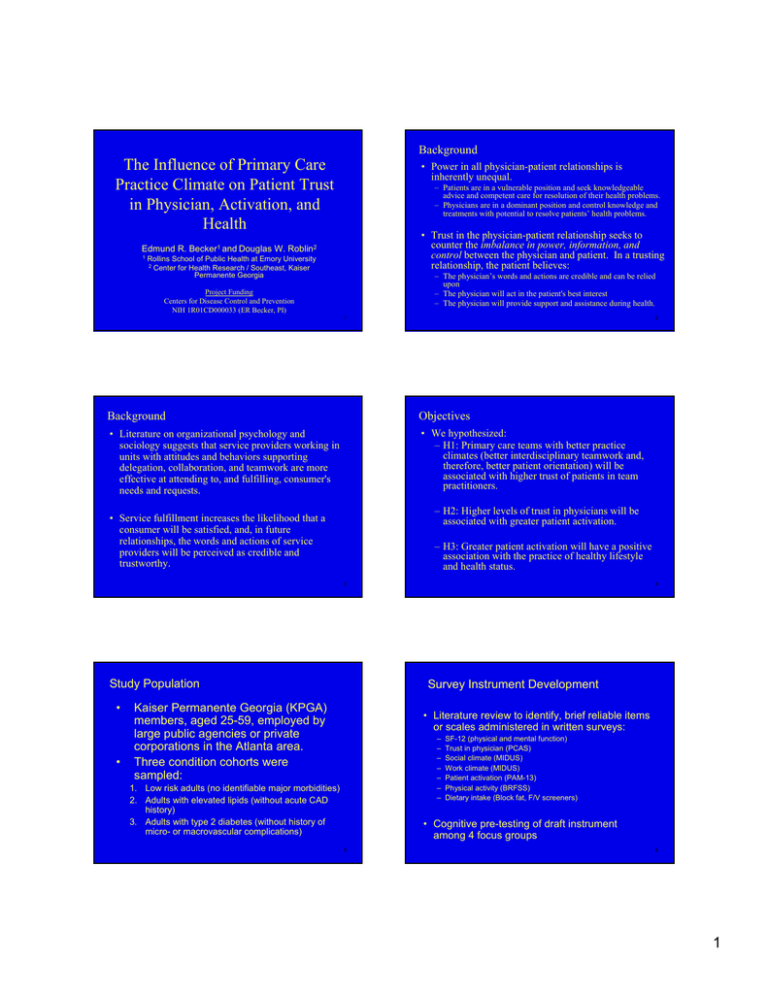

Background The Influence of Primary Care Practice Climate on Patient Trust in Physician, Activation, and Health • Power in all physician-patient relationships is inherently unequal. – Patients are in a vulnerable position and seek knowledgeable advice and competent care for resolution of their health problems. – Physicians are in a dominant position and control knowledge and treatments with potential to resolve patients’ health problems. • Trust in the physician-patient relationship seeks to counter the imbalance in power, information, and control between the physician and patient. In a trusting relationship, the patient believes: Edmund R. Becker1 and Douglas W. Roblin2 1 Rollins School of Public Health at Emory University 2 Center for Health Research / Southeast, Kaiser Permanente Georgia – The physician’s words and actions are credible and can be relied upon – The physician will act in the patient's best interest – The physician will provide support and assistance during health. Project Funding Centers for Disease Control and Prevention NIH 1R01CD000033 (ER Becker, PI) 1 2 Background Objectives • Literature on organizational psychology and sociology suggests that service providers working in units with attitudes and behaviors supporting delegation, collaboration, and teamwork are more effective at attending to, and fulfilling, consumer's needs and requests. • We hypothesized: – H1: Primary care teams with better practice climates (better interdisciplinary teamwork and, therefore, better patient orientation) will be associated with higher trust of patients in team practitioners. – H2: Higher levels of trust in physicians will be associated with greater patient activation. • Service fulfillment increases the likelihood that a consumer will be satisfied, and, in future relationships, the words and actions of service providers will be perceived as credible and trustworthy. – H3: Greater patient activation will have a positive association with the practice of healthy lifestyle and health status. 3 Study Population • • 4 Survey Instrument Development Kaiser Permanente Georgia (KPGA) members, aged 25-59, employed by large public agencies or private corporations in the Atlanta area. Three condition cohorts were sampled: • Literature review to identify, brief reliable items or scales administered in written surveys: – – – – – – – 1. Low risk adults (no identifiable major morbidities) 2. Adults with elevated lipids (without acute CAD history) 3. Adults with type 2 diabetes (without history of micro- or macrovascular complications) SF-12 (physical and mental function) Trust in physician (PCAS) Social climate (MIDUS) Work climate (MIDUS) Patient activation (PAM-13) Physical activity (BRFSS) Dietary intake (Block fat, F/V screeners) • Cognitive pre-testing of draft instrument among 4 focus groups 5 6 1 Survey Administration Practice Team Sample and Survey • Mixed mode survey (mail or Internet) conducted by a professional survey firm from 10/1/05 thru 12/31/05 • 2,224 respondents among 5,309 sampled (42% response rate) • Primary care practitioners and support staff affiliated with the 16 primary care teams in 2004 • Written survey administered during team meetings in June/July 2004 – Respondents more likely to be female, older – Diverse respondent sample: 60% female, 45% African American, 18% HS education or less, 31% household income < $50,000 – 35 items – 83 practitioners (MD, PA, NP) among 97 (86% response rate) – 158 support staff among 187 (85% response rate) • Psychometric properties of previously validated scales were similar between these survey respondents and respondents to surveys where scales were initially used. 7 8 H1: Practice Climate as an Antecedent of Trust H1: Practice Climate as an Antecedent of Trust • Dependent variable: Trust in physician (PCAS; Safran et al. 1998) measured at the patient-level • Patients empanelled to primary care teams with more favorable practice climates had significantly higher average trust in their primary care physicians than patients empanelled to teams with less favorable practice climates. – 9 item scale scored 0 (lowest) to 100 (highest) – Cronbach’s α = 0.90 • Independent variable: Overall practice climate measured at the team-level – Average of 7 subscales (e.g. autonomy, team ownership, role collaboration, task delegation) scored 0 (lowest) to 100 (highest) • Fixed effects hierarchical linear regression of patient (N=2,224) nested with primary care practice team (N=16) accountable for their care – Covariates: age, gender, condition cohort, race, martial status, and education – β = 0.11 point change in trust per point change in practice climate (p ≤ 0.05) • Patients empanelled to primary care teams with more favorable practice climates were significantly more likely to attribute “a lot” of influence on their exercise or diet than patients empanelled to teams with less favorable practice climates. 9 H1: Practice Climate as an Antecedent of Trust 10 H1: Practice Climate as an Antecedent of Trust Primary Care Team Influence on Exercise ("A lot of Influence" - "No Influence") by Quartiles of Trust in Physician P redicted Trust in Physician and 95% C onfidence Intervals by Low est to Highest Team Practice C lim ate Scores 30 Difference in Percent of Respondents Stating "A lot" and Percent Stating "None" 68 67 65 64 63 62 st 15 he 25 20 15 10 5 0 LOWEST MID-LOW MID-HIGH HIGHEST -5 -10 -15 -20 -25 ig 14 13 12 11 9 10 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 w es t 61 H Lo Predicted Trust 66 -30 Team s (O rdered by Practice Clim a te S cores) Respondents Classified by Quartiles of Trust in Physician Predicted Trust Exercise 11 Diet 12 2 H2: Influence of Trust on Patient Activation H2: Influence of Trust on Patient Activation • Dependent variable: Patient activation measure, short-form (PAM-13; Hibbard et al. 2005) measured at the patient-level • Patient activation was significantly, positively associated with trust in physicians. – 13 item scale scored 0 (lowest) to 100 (highest) – Cronbach’s α = 0.95 – β = 0.20 point change in patient activation per point change in trust in physician (p ≤ 0.01) • Independent variable: Trust in physician (PCAS; Safran et al. 1998) measured at the patient-level – 9 item scale scored 0 (lowest) to 100 (highest) – Cronbach’s α = 0.90 • Patients in the upper quartile of trust in physician had significantly greater average activation than patients in the lower quartile of trust in physician. • Ordinary least-squares linear regression – Covariates: age, gender, condition cohort, race, martial status, and education 13 H3: Influence of Patient Activation on Lifestyle and Health H2: Influence of Trust on Patient Activation • Dependent variables: Predicted Activation and 95% Confidence Intervals by Quartiles of Trust in Physician – – – – 78 76 Predicted Activation 74 73.5 72 70 67.2 66 – 13 item scale scored 0 (lowest) to 100 (highest) – Cronbach’s α = 0.95 63.7 62 • Ordinary logistic or least-squares linear regression 60 LOW EST Recommended exercise level (BRFSS) Dietary intake (Block fat and F/V screeners) BMI HbA1c (diabetes cohort), lipids (diabetes and elevated lipids cohorts) • Independent variable: Patient activation measure, short-form (PAM-13; Hibbard et al. 2005) 69.6 68 64 14 MID-LOW MID-HIGH HIGHEST – Covariates: age, gender, condition cohort, race, martial status, and education Trust in Physician Quartiles Predicted Activation 15 H3: Influence of Patient Activation on Lifestyle and Health 16 H3: Influence of Patient Activation on Lifestyle and Health • Patients with higher activation were more likely (p<0.05) to report recommended exercise levels. • Patients with higher activation had better dietary intake: Predicted Probabilities and 95% Confidence Intervals for Achieving Recommended Exercise Levels by Quartiles of Activation 80% 75% 70% Predicted Probability 68.1% – lower fat intake (p<0.05) – higher F/V and fiber intake (all p<0.05). • Patients with higher activation had lower average BMI (p<0.05). • Adults with diabetes or elevated lipids had higher average HDL (p<0.05). 65% 60% 59.5% 55% 53.2% 50% 45% 44.1% 40% 35% Least Activated Mid-Low Mid-High Most Activated Activation Quartiles Predicted Probability 17 18 3 H3: Influence of Patient Activation on Lifestyle and Health Predicted P ercent Fat in D iet by Q uartiles of Activation 47 Predicted Percent Fat 46 46.0 45.0 45 44.4 44 Conclusions • Collaboration and teamwork among practitioners and support staff in primary care teams is one factor ultimately contributing to patient health. • Practice climate does not influence patients' lifestyles and health directly, but appears to be mediated by how practice climate influences patient trust and patient activation. 43.4 43 42 Le ast Activated M id-Lo w M id-H igh M ost Activated Activa tion Q uartile s P redicted P ct Fat 19 20 Conclusions • Understanding the role of these mediating factors is important. As Hibbard (HSR, 2005, p. 1919) summarizes the importance of patient activation: – “[W]hen clinicians encourage patient engagement in their care, they do so blinded to any information on the patient’s capabilities for taking on a self-management role. What often results is a “one size fits all” patient education approach. If, however, clinicians had information on their patients’ level of knowledge and skill to self-manage, they could target self-care education and support to individual patient needs and presumably be more effective in supporting patient’s self-management.” • A favorable practice climate supporting the ability of a practice team to better attend to patient needs and values, and tailor prescriptions to those needs and values, may be a key element for achieving effective care delivery and health outcomes. 21 4