Spillover Effects of State Mandated-Benefit Laws

advertisement

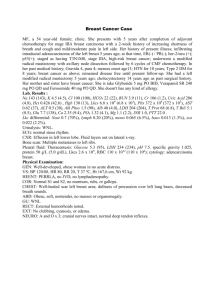

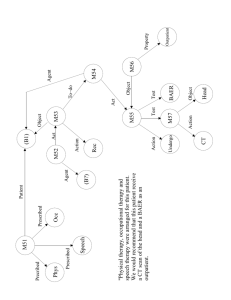

Spillover Effects of State Mandated-Benefit Laws The Case of Outpatient Breast Cancer Surgery June 5, 2007 John Bian, Ph.D., Atlanta VAMC, American Cancer Society Joseph Lipscomb, Ph.D., Emory Rollins School of Public Health Michelle M. Mello, J.D., Ph.D., Harvard School of Public Health Acknowledgement: The authors thank Jennifer Pomeranz for her assistance in a careful review of state mandated-benefit laws relating to breast cancer surgery. State Mandated-Benefit Laws States have been particularly active in passing laws relating to breast cancer treatment. – E.g., laws protecting patients from increasing popular practice of “drivethrough” mastectomy/breast-conserving surgery (BCS) with lymph node dissection (LND) (Case et al. 2001; Warren et al. 1998; NCI 2005). State laws formally affect only state-regulated insurers (e.g., not self-insured employer-sponsored plans, Medicaid, or Medicare). 2 congressional bills—Breast Cancer Patient Protection Act of 1997 and 2005—in part designed to expand coverage for populations exempted from the state regulation (e.g., ERISA preempts state regulation of HMOs). However, some evidence suggests indirect effects of state laws on populations exempted from the laws (Liu et al. 2004). Hypothesis: Spillover Effects of the Laws Physicians tend to treat all patients similarly regardless of insurance type. – Void costs of treatment differentiation (Glazer and McGuire 2002; Glied and Zivin 2002), – Lack sufficient information about exemption details of the laws (Liu et al. 2004). Data Sources Information on state breast cancer surgery laws in 12 states with SEER registries from 1991-2006. – LexisNexis legal research database: state statutes, bills, and administrative codes. – Follow up, if needed, with key informants in state legislatures and agencies. 1993-2002 linked SEER-Medicare claims data. – SEER cancer registry data – Medicare claims and enrollment data 1993-2002 county-level HMO enrollment file (provided by Dr. Laurence Baker, Stanford University). County-level Area Resource Files. Patient Sample Registries from CT, NM, CA, GA, HI, IA, WA, MI, and UT* Women age 65+ years Diagnosed with early stage 0-II unilateral breast cancer from 1993-2002 Breast cancer as the first-ever-diagnosed cancer FFS patients with both Part A and B benefits at the month of diagnosis Receiving unilateral mastectomy or BCS with LND. 24897 mastectomies vs. 17579 BCSs with LND. *Excluding NJ, LA, KY, and the reminder of CA because they were not in the SEER until 2000. Rural GA excluded due to unreliable linked data. Variables Dependent variable: – Surgery delivery setting: 1 if hospital outpatient (<24 hours) or 0 inpatient, determined from claims data. Key explanatory variable: – State law in effect: 1 if a patient in CT, NM, CA, and GA (with laws) and receiving a surgery post adoption of law or 0 otherwise. Covariates: – Patient/county-level characteristics (e.g., HMO penetration). Econometric Models Difference-in-differences (DD) analysis – Linear probability models with county & time fixed effects for estimating average effects of the laws. – Separate analyses of mastectomy and BCS with LND patients. – Huber clustered (county) standard errors correction. Sensitivity analyses – Potential sorting of outpatient mastectomy into outpatient BCS. Restrict the sample to stage 0-II patients receiving outpatient mastectomy or outpatient BCS with or without LND. Dependent variable: 1 if BCS or 0 if mastectomy. – Potential varying effects of laws over time. Results Estimates from DD Analyses Spillover effects of the laws Lowered likelihood of outpatient delivery of mastectomy by 5.0 percentage points (P < .001) — a reduction of over 30%. The effects on outpatient mastectomy became insignificant beyond 1st 24 months post adoption of laws. No significant impact on utilization of outpatient BCS with LND. Potential sorting of outpatient mastectomy into outpatient BCS. Limitations Sorting mechanism may dilute effects of laws. Cross-state spillover effects may bias estimates toward nil (more than 20 states passed similar laws from 1997-2002). Laws with varying mandates not modeled separately. Limited generalizability (9 states studied). Conclusions State mandated-benefit laws studied here had a substantial spillover effect on outpatient utilization of mastectomies among Medicare FFS breast cancer patients — a large population exempted from the state laws. The effectiveness of a proposed federal law may be hampered. Our findings provide the public with timely evidence for informed debate about the Breast Cancer Patient Protection Act of 2005.