Primary Care Physician Response to a Mental Health Carve-Out: An Economic Analysis

advertisement

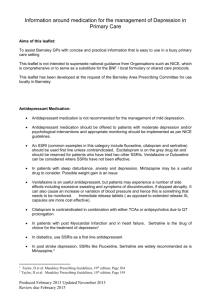

Primary Care Physician Response to a Mental Health Carve-Out: An Economic Analysis Ashley Aull Dunham Jennifer L. Troyer William P. Brandon UNC-Charlotte Carve-Outs Exclude specific services from prepaid health plans “Specialists” manage benefits Distinct budgets, provider networks and incentive arrangements Effect on Primary Care Physicians? Project Background Mecklenburg County (Experimental) n=3497 Mandatory Medicaid HMO enrollment in mid-1990s Mental Health, Dental Care and Prescription Drug Carve-Out – absolved HMO of both responsibility and risk New Hanover County (Control) n=969 Traditional FFS Incentive Structures Mental Health FFS and Primary Care FFS (Control) “Traditional” incentive to increase business volume Primary care will refer mental health only when timeconsuming or problem cases that prevent wealth maximization Primary Care Capitation with Mental Health Carve-Out (Experimental) Clear incentive to move mental health out of primary care Does this conflict with the patient’s best interest? Data Available Encounter forms not reliable Claims data for antidepressant prescriptions by all providers and visits provided by mental health professionals coded for depression Research considers the effect of a mandatory Medicaid mental health carve-out (that precludes reimbursement for mental health in primary care) on depression treatment for a sample of Medicaid recipients. Methods – DID Models Yit = β0 + β1Countyi + β2Phaseint + β3Postt + β4(Countyi)(Phaseint) + β5(Countyi)(Postt) + εi Claims/month submitted by mental health providers coded for depression Antidepressant prescription claims/month Antidepressant prescription claims/month submitted by mental health providers Antidepressant prescription claims/month submitted by non-mental health providers Methods – Logit Models Pr(Yit=1) = β0 + β1Countyi + β2Carveoutit + β3(Countyi)(Carveoutit) + β4Racei + β5Genderi + β6Agegrpi + β7Categoryi + β8Timeoni +εi Probability that a mental health provider prescribed antidepressants (as opposed to all other providers) Probability of antidepressant claims in a sample of all drug claims Effects of the Mental Health Carve-Out (DID Models) Mental Health Visits Total Antidepressant Claims Claims Prescribed by Non-Mental Health Providers -1.43068** Claims Prescribed by Mental Health Providers 0.86485 County -1.96645* Phasein .74444 2.92664* 3.79998* -.87334 Post -1.20064** 6.41282* 5.35710* 1.05572** (County)(Phasein) -0.15785 -2.14449** -3.75920* 1.54743** (County)(Post) -3.24974* -3.69659* .37957 *p < .05 **p<.10 2.31707* -2.22826* Effects of a Mental Health Carve-Out (Logit Models) County Carve-out (County)(Carve-out) Race Gender Agegrp Category Timeon *p < .05 **p<.10 Pseudo R2=.2121 n=861 Antidepressant Prescribed by a Mental Health Provider .8583447 .6562034 -1.112025 1.756301* -1.238316** 2.634148* -1.130781 .0251983* Pseudo R2=.1082 n=41,477 Drug Claim Being an Antidepressant .5297924** .4082136 -.1327179 1.333435* -.2423945 1.687171* -.792415 -.0048483 Results – DID Models Significant increase in mental health claims for depression (supports theory of wealth maximization) Increase in referrals may have only been for severe depression – in the patient’s best interest Decrease in antidepressant claims from mental health providers and no change in antidepressant claims from non-mental health providers Primary care providers continued to treat for depression by prescribing (free good) – allows wealth maximization while continuing to serve the patient’s best interest Results – Logit Models No significant change in prescriptions for antidepressants and no change in probability that prescription came from a mental health provider Decreased likelihood that mental health providers used antidepressants No additional barriers to getting antidepressants relative to all other drugs by eliminating primary care reimbursement for mental health Conclusions Physician’s utility function defined by many factors, including wealth maximization and their obligation to serve as a perfect agent Data suggests their obligation to serve as advocate was more powerful than their need to maximize wealth Removed from reimbursement arrangements and small portion of their patient population Less sensitive to reimbursement changes Implementation of capitation with the Medicaid population did not cause uniform change in behavior