SUPREME COURT OF NEW JERSEY A-8-08 September Term 2008

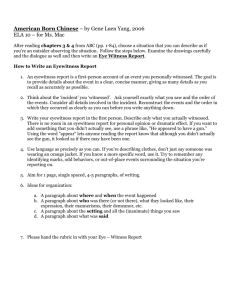

advertisement