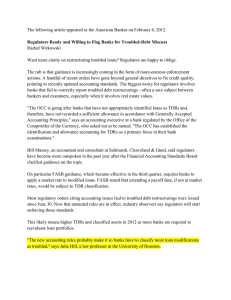

How Well Can Markets for Development Preservation Program

advertisement