Improving Human Health by Increasing Access to Natural Areas: Opportunities and Risks

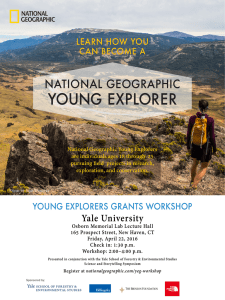

advertisement