Behavior with time-inconsistent preferences

advertisement

Modeling self-control problems I:

Multi-self vs. temptation

Lectures in Behavioral economics

Spring 2016, Part 2

People have demand for commitment

Ariely & Wertenbroch (2002)

Experiment where the students in a course had to hand in three

compulsory assignments before the final exam, they could choose

deadlines, and were punished if the deadlines were not observed.

Result: Many choose deadlines before the end of the semester,

& among these, students with evenly spread deadlines did better.

08.03.2016

G.B. Asheim, ECON4260, #2

1

Present-biased preferences: (EG)-pref.

U t (ct ,! , cT ) u (ct ) E ¦W

T

t 1

3

G.B. Asheim, ECON4260, #2

Hyperbolic discounting leads to time-inconsistent

preferences (Strotz, 1956), procrastination of tasks

with immediate cost, and makes commitment desirable, given awareness of the self-contr. problems.

Other ways to model the demand for commitment?

08.03.2016

G W t u (cW )

Yields time-inconsistent preferences.

Behavior with time-inconsistent preferences

Naive behavior: Choosing the best plan under the

presumption that it will be followed.

Sophisticated behavior: Choosing the best plan

among those that will actually be followed.

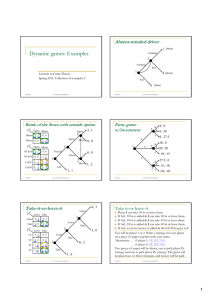

Multi-self model of sophisticated behavior: Let

every decision node correspond to a different “self ”.

08.03.2016

G.B. Asheim, ECON4260, #2

2

Outline

”Do it now or later”-article

O’Donoghue & Rabin (1999).

Interesting application of the multi-self approach

showing that sophisticates need not

realize better outcomes than naifs.

Problems with the multi-self approach

Alternative to the multi-self approach

Gul & Pesendorfer (2001, 2004).

Direct modeling of temptation.

Soft paternalism (”Nudge”)

08.03.2016

4

G.B. Asheim, ECON4260, #2

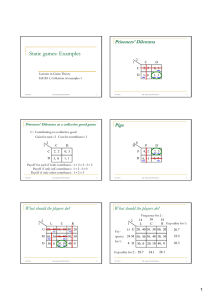

“Do it now or later” O’Donoghue & Rabin (1999)

Model: ʀ Must perform an activity exactly once.

“Do it now or later” (2)

ʀ T f periods in which to perform it.

Two

cases:

ʀ Each period, choose to “do it” or “wait”.

ʀ If wait until period T, must do it then.

If activity is done in period t, incur cost ct t 0 and

receive reward t 0.

ʀ Immediate costs: incur cost when you do

it, receive reward after some delay.

ʀ Immediate rewards: receive reward when

you do it, incur cost after some delay.

Assume (EG)-preferences with G (for simplicity):

Period-t utility for “do it” in period W t t:

For immedi ate costs : U t

vt

Reward schedule : v { (v1 , ! , vT )

For immedi ate rewards : U t

Cost schedule : c { (c1 , ! , cT )

08.03.2016

G.B. Asheim, ECON4260, #2

5

4

T

08.03.2016

Reward schedule : v { (0, 0, 0, 0)

Cost schedule : c { (3, 5, 8, 13)

Period-t utility

for “do it” in

period W t t:

W

t

3

0 (12)

1

W

2

5

2

W 3

4

( 2)

t 1 (23)

t

2

W

(3)

(3)

(1)

4

5

2

4

13

2

( 4)

13

2

( 4)

(3)

(1)

( 2)

132

4

5

(1)

( 2)

13

2

8

7

G.B. Asheim, ECON4260, #2

­E vW cW if W t

®

¯E vW E cW if W ! t

­vW E cW if W t

®

¯E vW E cW if W ! t

G.B. Asheim, ECON4260, #2

6

“Do it now or later”: Ex. with immediate costs (2)

“Do it now or later”: Ex. with immediate costs

1

2

E

Naifs do it in

period 4.

Sophisticates do

t 3

it in period 2.

08.03.2016

Welfare comparisons of naive & sophistic. behavior:

W 2 is better than W 4 at both t 0, t 1 and t 2.

W 2 cannot be compared with W 4 at t 3.

Period-t utility

for “do it” in

period W t t:

Naifs do it in

period 4.

t

W

3

0 (12)

W

1

2

5

2

( 2)

t 1 (23)

t

5

2

(1)

5

2

( 2)

Sophisticates do

t 3

it in period 2.

08.03.2016

W 3

4

W 4

132

(3)

4

( 4)

132

(3)

4

( 4)

132

(1)

8

(3)

132

( 2)

(1)

8

G.B. Asheim, ECON4260, #2

“Do it now or later”: Ex. with immediate rewards

1

2

E

4

T

Naifs do it in

period 3.

Period-t utility

for “do it” in

period W t t:

Reward schedule : v { (3, 5, 8, 13)

“Do it now or later”: Ex. with immediate rewards (2)

Cost schedule : c { (0, 0, 0, 0)

W

t

0

t 1

t

1

W

2

W

3

W

4

13

2

( 2)

( 4)

(3)

4

5

2

3

(3)

( 4)

5

2

3

2

2

Sophisticates do

t 3

it in period 1.

08.03.2016

4

( 2)

(1)

13

2

(1)

(1)

(3)

( 2)

13

2

4

5

( 2)

(1)

13

2

8

9

G.B. Asheim, ECON4260, #2

General lesson: Sophistication about future self-control problems can mitigate or exacerbate misbehavior

11

G.B. Asheim, ECON4260, #2

Welfare comparisons of naive & sophistic. behavior:

W 3 is better than W 1 at both t 0 and t 1.

W 3 cannot be compared with W 1 at t 2 and t 3.

Period-t utility

for “do it” in

period W t t:

Naifs do it in

period 3.

t

W

1

W

3

2

0

2

W

5

2

( 4)

(3)

3

W

( 2)

( 2)

(1)

13

2

4

( 2)

4

(1)

13

2

4

( 4)

5

2

13

2

4

(3)

5

2

3

t 1

t

Sophisticates do

t 3

it in period 1.

08.03.2016

Proposition 2. For both immediate costs and

immediate rewards, Ws d Wn.

ʀ Why? The future is always more promising from the

point of view of a naif, since a sophisticate removes some

future possibilities as unattainable without commitment.

Hence, for a sophisticate the present is relatively more

attractive, leading to the task being performed earlier.

ʀ With im. costs: Naifs may procrastinate due to presentbiased preferences. With im. rewards: Sophisticates may

preproperate since they realize their future misbehavior.

08.03.2016

(3)

(1)

13

2

8

(1)

( 2)

10

G.B. Asheim, ECON4260, #2

Propositions 3 and 4. When evaluated from a prior

period 0, the following holds. For immediate costs, a

small self-control problem can cause servere welfare

losses if and only if you are naive. For immediate

rewards, a small self-control problem can cause servere

welfare losses if and only if you are sophisticated.

ʀ Why? Naifs with immediate costs may procrastinate

repeatedly even if E is close to 1.

Sophisticates with immediate rewards may preproperate

repeatedly even if E is close to 1.

General lesson: Even “small” self-control problems

can cause servere welfare losses.

08.03.2016

12

G.B. Asheim, ECON4260, #2

Procrastination example revisited

A task to be performed at time 0, 1, 2, …, or not at all.

Immediate cost: 25. Benefits at the next stage: 125.

(E, G)-preferences with E

50

40

1/2 and G 4/5.

But not

Better worthwhile

to do it

to never.

wait for

now than

2 periods

Sophisticated behavior with 3 periods

32

time

8

10

25

Even better to do it at the next stage.

08.03.2016

13

G.B. Asheim, ECON4260, #2

Backward induction

Let every decision node correspond to a different

“self” or “agent” of the decision-maker

Backward induction

Self a time 1 if

A sophisticate task was not

does the task done at time 0

now, since else

postponed for

2 periods.

Self a time

0

08.03.2016

0

1

2

24

30

Payoff of

0-self

30

25

25

Payoff

of 1-self

14

G.B. Asheim, ECON4260, #2

Sophisticated behavior with odd # periods

Sophisticated behavior with 4 periods

A sophisticate

does the task

with a delay

of 1 period.

A sophisticate does the task now, since else

postponed for 2 periods.

Sophisticated behavior with even # periods

A sophisticate does the task with a delay of 1 period.

Conclusion: Multi-self model with sophisticated

behavior may not be descriptively accurate

0

1

08.03.2016

3

2

15

G.B. Asheim, ECON4260, #2

Is it “right” to apply the multi-self model?

Introduce naivete (or partial naivete) (O’Donoghue & Rabin,

08.03.2016

1999, 2001)

16

G.B. Asheim, ECON4260, #2

Sophisticated behavior with f periods

If we impose that behavior is the same in all

periods, conditional on the task not having

been done, there is a unique equilibrium, where

the task is done in each period with prob. ½.

It is another equilibrium (planning) to do the task in

periods 1, 3, 5, …, but not in periods 0, 2, 4, … .

It is an equilibrium (planning) to do the task in

periods 0, 2, 4, …, but not in periods 1, 3, 5, … .

Backw. induct. cannot be used since no last period

Demand for commitment

Utility at t of doing the task at

30

W 1

24

W 2

W 0

3

¼ prob.

½ prob.

2

25

0

08.03.2016

1

0

1

2

3

Suppose the decision maker can purchase a commitment device costing c, ensuring that the task be

done in the next period? What is the largest c?

With an odd # periods, she does the task now with

present payoff 25. Commitment to next period

yields payoff 30 c. Hence, c cannot exceed 5.

With an even # periods, she does the task in the

next period anyway. Not interested in commiting.

With f periods, she receives a payoff of 25.

Commitment to next period yields payoff 30 c.

Hence, c cannot exceed 5.

08.03.2016

17

G.B. Asheim, ECON4260, #2

Temptation (Gul & Pesendorfer 2001)

a : Doing the task

1

G.B. Asheim, ECON4260, #2

18

Temptation in a dynamic setting

(Gul & Pesendorfer 2004)

a : Not doing the task

0

In standard consumer theory, if a1 is preferred to a0 ,

then she has the following preference over menus :

{a1} ~ {a0 , a1} ; {a0 }

No time-inconsistency; the future is discounted by G

Still, temptation yields a demand for commitment

Payoff when choosing a1 : 25 54 125 t

In G & P' s analysis, if tempted by a0 and gives in :

Payoff when choosing a0 :

{a1} ; {a0 , a1} ~ {a0 }

0

4

5

W0

Maximal payoff when task has not been done :

If tempted by a0 , but does not give in :

G

{a1} ; {a0 , a1} ; {a0 }

08.03.2016

19

G.B. Asheim, ECON4260, #2

W0

max{75 t , 54 W0 }

t : Cost of temptation

4

5

08.03.2016

20

G.B. Asheim, ECON4260, #2

Temptation in a dynamic setting (2)

Optimal not to give in at a low cost of temptation ( t 75 )

W0

75 t ! 0

W > 0 0

4

5

W

0

Optimal to give in at a high cost of temptation ( t t 75 )

W0

0

W0 t 75 t

Temptation and the demand for commitment

Assume that she can commit by paying c to doing

the task in the next period (without being tempted).

Wc

0c

4

5

25 54 125

60 c

Optimal to commit at a low cost of temptation ( t 75 ) if

60 c ! 75 t

Wc

W0

c t 15

Optimal to commit at a high cost of temptation ( t t 75 ) if

Wc

08.03.2016

21

G.B. Asheim, ECON4260, #2

60 c ! 0

08.03.2016

W0

c 60

22

G.B. Asheim, ECON4260, #2

Soft paternalism

With procrastination,

the status quo matters

E.g. organ donation,

savings decisions

Organ donation:

Opt out. Austria:

99.98 % consent

Opt in. Germany:

12 % consent

Active choice.

US driver’s licence

08.03.2016

23

G.B. Asheim, ECON4260, #2