'BLAME' AS INTERNATIONAL BEHAVIOR A contribution to inter-state interaction theory*

advertisement

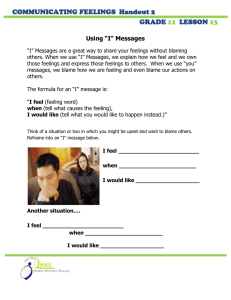

'BLAME' AS INTERNATIONAL BEHAVIOR A contribution to inter-state interaction theory* By HELGE H V E E M International Peace Research Institute, Oslo 1. Introduction The intention of this paper is to present some ideas on the role of a dimension which has relevance to several fields of International Relations theory: to a theory of conflict, to the theory of sanctions, or generally to a theory of interstate interactions. This is the 'blamepraise' dimension. Two assumptions lie at the basis of the proposal that this dimension is worthwhile studying. First, that it may be separated analytically as a specific form of inter-state behavior. Second, that it is related to some fundamental aspects of the international system and its actors. I postulate that high prestige or 'good reputation' is of some value to all actors in the system, and that consequently they will seek 'praise' to avoid 'blame'. Or, as North et al. have noted, the behavior of a state can be viewed as adjustment activities in the effort to achieve an optimal balance of unavoidable punishment to preferred reward. 1 The case for this postulate should be relatively clear. The widespread criticism of the United States' policy and presence in Vietnam is and must be of some concern to the US government. The outside blaming which the invasion of Czechoslovakia inflicted upon the Soviet Union and allied states' leadership must have been considered or at least strongly felt afterwards by the same states. Even if the super powers would probably be less hurt by blame than smaller powers, they 4 Journal of Peace Research would consider it to be in their 'national interest' to be 'praised' or 'rewarded', and to avoid being 'blamed' or 'punished'. The case is also found in the informal rule of the international system that bad behavior ought to be criticized, i.e. it is a 'moral obligation' for any actor in the system to act out against those actors who break the formal or informal standards of behavior of the system. Such a view is seen behind the thinking of many leaders of smaller states who see it as their duty to act as the 'bad conscience' of the world. In particular it is seen in the philosophy of the 'actively neutralist' countries. 'Blame' or 'praise' may also be deliberately chosen acts where others forms of behavior are not available, or where this particular form of behavior is preferred to other available forms. To some states, particularly the small ones which lack other resources, blaming may be the only form available. In this respect it may not even be related to any particular act or behavioral trend which 'deserves' blame. 2 2. Definitions and scope By the term 'blame' I mean an act of criticism, verbal or written, by one actor of another; it is an act of negative evaluation. 'Praise' on the other hand is understood as an act of approval or of expressing positive evaluations. For an act of blame or praise to be relevant to international politics, it has to be communicated by a representative of the 50 Helge Hveem blaming (praising) actor, the sender, and recognized by a representative of the blamed, the receiver, and/or by third parties. A representative is an official governmental or diplomatic person whose status is recognized by formal or informal conventions. The role or junction of blame and praise is at least potentially manifold. It has potential relevance to four very basic dimensions of international politics: the conflict vs. peace, the violent vs. non-violent, the integrative vs. disintegrative, and the balancing or equilibrating vs. imbalancing dimensions. To give some examples: blame is a form of (negative) conflict behavior, while praise (most often?) is peaceful or peace-creating behavior. Further, blame is a form of non-violent conflict behavior. Even further, blame and praise may have both integrative and disintegrative functions, depending on what level of the system one is studying, and on certain other factors. Lastly, blame and praise may have consequences for the internal equilibrium of an international system, both in the equilibrating and the disequilibrating direction. For analytic purposes, one may distinguish between four systems: the sender; the receiver; the sender-receiver relationship; and the wider, environmental system of sender, receiver and third parties. Since I am particularly concerned with relational aspects of state behavior, in state interaction I shall focus on the latter two systems. Blame and praise may be the result of, result in, or in some way be related to other forms of state behavior or interaction between states. Blaming another state is of course, or should at least be, 'due to something'. In most cases it may be seen as a response to an act performed by another, but as we know this is not always so: there is always the case of the alleged plot, sub- version etc. and blaming in such cases may be due to other factors or aims on behalf of the sender. Acts of blaming and praising of course will have to be correlated with other forms of interaction to look after possible (causal) relations. I should also stress that I chose to focus on state behavior, i.e. the national state is our unit. One could very well have applied our ideas to interaction between other units, e.g. intrastate units interacting with corresponding units in other states or with the very states themselves. Thus, in the case of the trade union or the national students' association of one particular country voicing very strong criticisms against some other country with the result that an official (state) protest (response blaming) from the receiver is directed against the corresponding official level of the sender, there might be the problem of deciding what is state interaction and what is not. Blame (praise) may be act-oriented (specific-oriented) or structure-oriented (general-oriented). The act-oriented blame aims at criticizing concrete political acts and change policy. The structure-oriented blame criticizes, seeks to change or even destroy the structure of the given system (ranging from the interaction system between the two actors to the environmental, global system). A third category would probably be actororiented blame, aimed at reducing an actor's position, without necessarily being aimed at structural change. This distinction is made mainly for analytical reasons; of course there will be combinations of the two types of orientation. Moreover, even if that has not been intended by the sender, the act of blame for the purpose of changing policy may very often have the consequence of changing the structure, or vice versa. To take only two, in this 'Blame' as International Behavior respect, contrary examples: the blaming of South Africa for its policy of apartheid is mainly oriented at changing this very policy, but has probably had greater success in lowering this country's prestige in the world and worsening its structural position in other respects; and the case of the victorious belligerents' treatment of Germany after World War I is probably an example of purposive blaming oriented at reducing that actor's prestige and position generally and through this also changing its 'warmongering' policy. There may seem to be an almost necessary connection between act-orientation and structure-orientation, in the sense that one empirically would find very few cases where the two aspects may be separated and did not in some way and to some degree, go together. Take the example of Sweden's blaming of the US policy in Vietnam. It might probably be stated (and I think some Swedish official did it) that this kind of blaming was only aimed at changing the policy pursued and did not in any way aim at attacking the very position or prestige of the US government generally. But US officials evidently did not take it that way: they perceived the criticism primarily as a means used by a Western country (that was the bad thing) to reduce its very prestige, in Swedish opinion and in the world. 3 4 The forms of blaming or praising behavior are many. One may distinguish between open and closed communication. Open blaming is the criticisms voiced in a speech by some state official, or generally the acts of political blaming which become generally or publicly known (to a greater audience, and to third states); closed blaming is the way of criticizing through diplomatic channels secretly and without calling the attention of third states. But another and a more important discrimination is 4 51 that between strong and moderate or weak blaming. 3. The measurement of blame The task of constructing scales for the measurement of the intensity of state behavior along the non-violent to violent, or weakly to strongly blame-oriented behavior, have been taken up by several authors. Although starting from somewhat different conceptions of the range and forms of behavior, North et al. in their crisis analysis, Rummel on conflict behavior, and McClelland et al. with their 'event-interaction' study have all developed scales and methods, parts of which may be adapted to my purpose. In the following, I shall deal only with the blame aspect of behavior or interaction, as I am particularly interested in conflict behavior. This leaves out a discussion of praise as positive sanction, a type of behavior which seems to be much neglected in literature. On the other hand, although I have started from the assumption that blame and praise were the two ends of one continuum, making blame-praise interaction a zero-sum game, I have the feeling that this assumption under certain conditions may be wrong. The diplomatic language, both as open and as closed communication, seems to be based on a cotume which consists of relatively commonly shared standards of behavior. When non-diplomatic behavior - the distinction between diplomatic, or formalized behavior and non-diplomatic is neither sharp nor particularly important - is considered, classification is more problematic. Rummel offers a typology of conflict behavior, which ranks twelve more or less distinct types of behavior from 'Anti-foreign demonstrations' as the least, 'War' as the most conflicting type of behavior. Zinnes has a corresponding 5 6 7 52 Helge Hveem number of categories, while McClelland and his collaborators, Martin and Young, use a higher number. To some extent differences between these authors are semantic or conceptual rather than theoretical and methodological. What they share is an emphasis on non-violent forms of behavior, while Kahn in his well-known escalation ladder concentrates on violent behavior. While Kahn's scheme for my purposes is too unspecific on the non-violent behavior side, I believe on the other hand that the classification should not be too specific or detailed either. Martin and Young in their study have collapsed the initial twenty-three into eight categories, which seems to be more appropriate both methodologically and theoretically. Rummel on the one hand, Martin and Young, and Zinnes on the other differ in their ranking of one category of blame, consisting of repulsion of diplomatic representatives or breaking of diplomatic relations etc., the former ranking such acts low, the latter high. I am inclined to take the latter's position. As I said before, it may be a problem to decide what constitutes the bottom and the top of the scale, i.e. what acts should be considered the most moderate forms of blame, and what acts occur at a point where the conflict is escalated into the threatening to use, or the outright use of violence. Such problems evidently will have to be decided on the basis of empirical evidence. 8 9 One may introduce several indicators of strong-weak blame to make the scale even more discriminating, but this would certainly make such a measure too overloaded. I venture only two. Open blame is generally stronger than closed and the blame voiced by the top representatives of an actor is stronger than when it is voiced by someone lower down in the internal hierarchy of that actor. Id est: it is more of a blame when it comes from President Nixon than from some State Department spokesman. The scale which I propose is partly my own and partly based on those already mentioned. It is: (1) Non-official blame: anti-foreign demonstrations, v i o l a t i o n s of R's property in S, etc. (2) Official blame: Political or diplomatic talks, exchanges; indirect criticism, initial 'points' are m a d e , disagreement verified. (3) Mild blame: m e m o r a n d u m , request of explanation, direct criticism. (4) Medium blame: complaints, protests, accusations. (5) Strong blame: strong protests, threat of reprisals, warning, d e m a n d of excuse, h e a v y criticisms, expulsion of private citizens. (6) Punishment: repulsion of diplomatic representatives, breaking of diplomatic relations, breaking of cultural agreements, etc. (7) Strong punishment: outright denunciation, breaking of political or military agreements, withdrawal f r o m alliance, etc. Blame, of course, may be combined with other acts and thus be bolstered up by or bolster up those other acts or means of conflict behavior. In that respect, we may distinguish between four levels: (1) B l a m e used alone. (2) B l a m e c o m b i n e d with the threatening of concrete, 'physical' punishment, e.g. econ o m i c sanctions - w h a t in the K a h n ladder is called 'subcrisis maneuvering'. (3) B l a m e c o m b i n e d with the implementation of s u c h threats, a n d / o r the threatening of serious physical punishment. (4) B l a m e c o m b i n e d with the implementation of serious physical punishment, e.g. severe sanctions, m o b i l i z a t i o n of troops, acts of military reprisals or warnings, etc. Clearly, this is where we reach the 'brink' in the escalation process, where the limit between non-violent and violent conflict is reached and by-passed, and where blame stops being the important act and becomes ritualistic, merely accompanying the other, stronger acts of conflict behavior. 'Blame' as International Behavior What we have so far looked into is the distinctions between strong and moderate blaming. There are at least three other dimensions for the qualification of the act of blaming: its volume, its support, and its scope. Let us briefly state what they imply. The volume of blaming is the number of times the blame is made at different time points during a given period. The support of the blame is expressed by the number of actors taking part in the blaming. The scope of the blame is the number of issues which the blame is based on. In one single expression of these dimensions — volume, support and scope taken together - I have what I shall call the blame intensity. 4. Blame: purposes and consequences What are the purposes of blaming? And what are its consequences - intended and non-intended? These questions will occupy us for most of the rest of this paper. In discussing them I shall make use of the four dichotomies introduced earlier. I have already taken the position that blame is definitely a kind of non-violent behavior. Thus, when it is accompanied with or 'overrided' by violent behavior in some form or other, we should no longer occupy ourselves with blaming as the main behavioral aspect, since the violent aspects will usually be considered more important, both to the two parties concerned, and to third parties. This is the situation where blaming is used, or has as its consequence, to escalate a conflict possibly onto the 'brink' where other and especially violent means are taken into use. But the act of blaming may also be used for the purpose of de-escalating a conflict, for instance in the sense that the blamer for some reason compensates for reducement in the use of violent (or other nonviolent) means by increasing the blame 53 volume and scope. His reason may be that he wants to keep the total conflict with another actor at the same level, or as high as possible, but below the level of violent conflict. As already mentioned, blame may be a means of policy chosen due to lack of other means which can be used: the case of the small power with no means of military or economic sanctions to inflict or threaten is evident. But it may also, both by the great and the small, be deliberately chosen among several means which may be at hand, some of them violent. When an actor in a conflict situation chooses the non-violent way of acting to violent means, easily available and in some respects perceived as more 'effective', this might be said to be an important aspect. In some ways it may even be said to constitute a positive element of conflict behavior, since non-violent behavior is preferred to violent (a preference which most often should be considered positive, although important exceptions, e.g. the liberation of occupied or colonized areas, may be found) and since it provides a 'safetyvalve' both in a bilateral relationship, and in the wider multi-actor system, which may release latent aggression under control. McClelland has put particular emphasis on analyzing the sources of and reasons for external opposition toward the United States, and he has made several proposals to that respect. Briefly, they are: differing national interests; differing national 'style'; war companionships are weakened, i.e. a weakening of old loyalties; 'secondary conflicts'; ideological differences; and what he calls 'collision courses'. McClelland formulates a research program which inter alia will aim at finding the ratio of American 'outputs' toward other actors to the opposition (and threatening opposition) from outside. 10 54 Helge Hveem While the program is sufficiently concrete to be a useful guide to others, it seems too much based on the source which the author himself names the national interest. The intent of this paper is to look as much as possible for symmetry in the relationship between the actors as well as try to keep a symmetric outlook ourselves. North et al. are more in line with such principles. They also present a number of hypotheses on the behavior of a sender-receiver relationship, and of the international system, in situations of varying degrees of reward and punishment, or differing perceptions of, expectations of such outcomes. The senderreceiver relationship is most systematically explored by Rummel who more than anyone else has developed behavior analysis on the level of the dyad. While there are works in that direction in the Rummel 'school', the other authors and schools mentioned seem to be relatively free of theory which relates state behavior to the structure oi the international system, or to the structure of the dyad (which of course is also an international system). To me this aspect seems to be the most interesting one. A theory of blame behavior should take notice of the fact that the international system is stratified, that many senderreceiver relationships will be highly asymmetric, and that there are varying degrees and forms of distances between actors. Before I develop these problems further, I shall mention four factors which will have some relevance both to the purposes, the forms and the consequences of blaming. Three of the factors relate to the sender-receiver relationship primarily, the fourth involves third parties (which may also be involved in the two first mentioned factors): (a) The sincerity of the blame, i.e. the degree to which the blame sent is 'be11 lieved' or taken for its 'face value' by the receiver (and third parties). Several factors may work in the direction of reducing the sincerity behind the act of blame, perhaps to the point where the blame appears as 'quasi-blaming'. One such factor may be that the relationship between sender and receiver on other and important interaction dimensions has a content of active and friendly exchanges. From the point of view of the receiver - and of third parties, to the extent that they know of the situation - the sincerity of the blaming in such a context may be reduced, and consequently its effect. Examples of this kind of relationship are easily found, for instance in the case of several small actors vis a vis USA. Or, perhaps more important and outstanding: the US blaming of the Soviet-Warsaw pact invasion of Czechoslovakia while at the same time making it clear that other basic relations, some of them stemming from mutual interests, would not be subject to sanctions. 12 On the other hand, the very fact that an actor blames another while at the same time keeping on with such other friendly interactions as trade, official visits, cultural exhibitions etc. with the other one, may be increasing the sincerity of the blaming. That is: the fact that the sender is considered a 'friend' gives him more access, he is really listened to; when you are criticized by an acknowledged friend, that most certainly has to be taken seriously. It is evident that such reasoning in fact lies behind much blaming behavior and blame evaluations. The essential question here seems to be the historical background of the relationship between two given actors. A relationship which has been built up consistently and over some time and which contains either positive or negative interaction on a range of dimensions (or the more important interac- 'Blame' as International Behavior tional dimensions) is more decisive for the sincerity to be attached to the sender by the receiver than a more inconsistent, short-lasting and single-dimensional relationship. We shall return to this point later on, in another context. Another part of this sincerity aspect is what might be called the 'reducibility' of the blaming - the tendency of the receiver to rationalize, to explain away the blame sent on him. The receiver may for instance evaluate the blame as sent for domestic political reasons: the leadership in the sender country uses the act of blaming, the picking of some outside scapegoat, to bolster its own political position inside the country. Or perhaps a more genuine kind of rationalization: the receiver accuses the sender for onesidedness, for having been misled by propaganda, for not really knowing or appreciating the policy or the motives of the receiver. (b) The second factor has to do with what I shall call the blame tolerance of the receiver actor, i.e. his ability to stand blame without being affected by it. That is: different actors may stand different degrees of blaming in different situations, so that the expected result (e.g. change in policy) does not show up. Factors which increase tolerance are the political decisiveness or will (to oversee or exclude the content of blaming from its information channels) of the actor; an authoritarian (domestic) political system which may isolate that will from outside or inside pressure; and the power of the actor which can be used to counteract or even prevent blaming by deterring another actor from blaming or for instance from escalating blaming into more serious, violent acts, or which can be used to 'buy out the blamers' foreign aid is the obvious example here - or at least modify the blame intensity. In connection with this last point, it should be stressed that blame, even if 55 it is of a relatively high intensity, does not de facto necessarily lead to change in policy or position. But, our assumption then is that if an actor, under the burden of a heavy blame volume, wants to continue its policy or keep its position (e.g. capability to influence other actors) it has to compensate for the damage inflicted upon it by the blaming through the use of such other means as foreign aid, sanctions (for instance the threat of withdrawing foreign aid) etc. One example, which seems to be both highly relevant and empirically correct, is the reaction of actors in the so-called 'third world' to the US policy in Vietnam: this has evidently not been so strong or damaging as one for several reasons would have thought (at least not among the actual leaderships of those actors). The reason for this of course may be that these actors, contrary to expectations, are not so interested in the Vietnam war and therefore do not care to make evaluations of it and of the actors involved. But it also seems safe to say that for a number of actors, their economic dependence on the USA and related factors have been at least as influential in the direction of non-blaming. From this one may generalize that the fact of being powerful, big is perhaps the most important factor in the creation of blame tolerance: the topdog stands much more than the underdog. Or, the topdogs may even stand an immense intensity of blame, because they have so vast resources to draw compensation from or to deter blame with. The development of the world's reactions to and views of the Soviet behavior in Czechoslovakia and the reactions of the Soviet Union to it will also be a point of empirical reference on this. In this case one would of course point to the two other tolerance-creating factorswill and authoritarianism (at least the last one) - as relatively more important 56 Helge Hveem to explain that the Soviet Union, in spite of relatively intense blaming from the outside world, did not change its policy of occupation. (This of course may be due to other factors and the same would be true in the case where the Soviet Union did or do make a change and for instance withdraw, but this we shall not discuss here.) From what I have just been saying, I may once more stress that the stratification of international systems is an important variable in the whole setting of blame tolerance and blaming effect. The general hypothesis is: 13 the topdog and at the age, obtain stands more blame from others same time may cause more dammore effect in blaming others. (c) The third factor is the frame of reference - the very norm or value scale used as the basis for blaming. There is no clear international consensus as to the relative strength of different acts of blame, and this lack of consensus may be even more felt when it comes to the international, formal and informal standards of making judgements of actors. There is the UN Charter, there is the Human Rights Declaration, the Red Cross Convention, etc. which in some fields and to some extent at least must be considered a general standard of inter-state behavior. But different actors may put different emphasis on the various pieces of content in such standards, and they most often do not give any priority to the different norms or to any hierarchy of values which can be universally applied. Blamer and blamed may thus place different weight on one and the same act or behavior system. One may probably distinguish between universal (global) and regional or sub-system norm scales, e.g. the UN frame of reference may be different, in some situations and to some actors, from that of the Communist world, or the Western world. Confusion or value clashes may result when different frames of reference are applied by sender and receiver. In such a situation, third party intervention as a 'judge' to the conflict, may be particularly relevant. (d) The saliency of the issues involved in the blaming, or of the very blaming itself, may be of some importance, particularly to the receiver. To the extent that the issues, the cases, etc. for which he is blamed are non-salient to him, he will tend to reduce the importance of the fact that he is being blamed. This may also be true with third parties in their position toward the sender-receiver relationship. Correspondingly, the more salient an issue is, the more seriously will the blaming be taken. 5. Blaming capability and blame effect Since I have expressed particular interest in the relation of blaming to the structure of an international system, it follows that what I called structureoriented blame will also be of particular concern in the following. As I said before, however, this is no important limitation of the perspective since act- and actor-oriented blaming will often have structural consequences or vice versa. As will be clear from what has been said so far, structure-oriented blaming has implications on both the vertical and the horizontal axis of the structure. Vertically, it has most often consequences for the rank or prestige of the receiver, and thus for the rank distance (or symmetry/asymmetry) between the sender and the receiver. It may also have certain consequences for the equilibrium of the given international system. Horizontally, it may have integrative or disintegrative functions, as already mentioned. Along the horizontal axis, it is also important to notice the role of the concept of political distance. 14 'Blame' as International Behavior By political distance I mean the generalized distance between two given actors in the system as measured by their relative political position - their attitudes or opinions on the more basic political issues in the system. Studying the behavior of any set of actors within a larger system of actors - the global political system is the 'over-system' which we superimpose on other smaller systems - the distance between two actors is always seen as relative to (all) other actors in the system. The anchoring or reference points most often used are the super-powers (ref. the series of UN studies we have had in recent years) and I think this both generally and in our case is a valid measure since they both in domain and scope are the systemdominant actors. The two super-powers are then chosen as end-points on a continuum and the political position of the different actors is induced from information about their attitudes on a range of political questions, relative to the attitudes of the two. 15 16 The concept of political distance, apart from its role as a variable, structuring horizontally international systems , for our purpose may be used in another context - the calculation of the probability that blaming will have any effect on the receiver. Such calculation may be done by combining political distance with rank in the system. Our hypothesis concerning the role of political distance is that the effect of blaming increases with decreasing political distance. That is: if an actor is blamed by some other actor close to itself by political distance, the effect is considered to be greater both to its own position and to the relevant international system than if it is blamed by an actor at relatively great political distance. Combining the two hypotheses we have made on rank distance and political distance, we arrive at the following 57 hypothesis, which is central in our scheme: The greater the rank distance (or asymmetry) between the sender and the receiver, with the sender being the high-ranking actor, and the smaller the political distance between them, the greater will be the effect of the blame. Political distance is taken to tell you something about a priori expectations of blame, from the point of view of the potential receiver and from third parties. To take only one example: USA (or any actors close to it by political distance) would usually expect heavy blaming from actors close to the Soviet Union. Such blame would be very 'ritualistic' at least in its consequences, and in the way it is evaluated by many third parties (if not by intention); it would be nothing to be disappointed about or take really seriously. The effect is zero. The blame of the non-aligned, neutralist, i.e. those actors which are situated between the two super-powers at some political distance from both of them, would be more to care about, not to speak of the blame coming from actors close to the big one (dominant not only in the global system, but even more within 'its own' subsystem or subsystems, its spheres of influence to which the sender in this case may belong). This kind of blame would generally be highly unexpected (i.e. if it is of a certain blame volume) both to the blamed and to third parties. It would definitely not be ritualistic, but break with the rules of the system, which says that you should blame your foes and praise your friends. The extreme case here is when the small, close-to-the-big actor and in important respects dependent upon him, criticizes him heavily (e.g. Norway blaming USA). The not so extreme would be that some middle-range power or aspiring great power (depending on the rank categorizations made) criticizes 'its own' super-power. This clearly has 58 Helge Hveem been the case in the relationship between USA and France under the Gaullist regime. We have now indicated the relationship between rank distance and political distance when it comes to effect probability calculation. But evidently a third dimension, what we above referred to as the blame intensity - which was a combined measure of the volume, the support and the scope of the blame - must be drawn in at this point. We shall do that by constructing a combined formal expression of all three dimensions. Or more correct: two expressions, one for the case where the effect (on the receiver) is studied, the other for the case of the sender's capability of blaming, his capability of creating any effect. These expressions or formulas are called blaming effect estimate and blaming capability estimate, respectively. From what we have said about the role of the three dimensions, one might conclude that political distance is essentially a means of reducing both effect and capability. The role of rank (used here more or less synonymously with power) seems to be somewhat different: when the focus is on the effect, it has the same function as political distance - reducing the effect. But in the case of blaming capability, rank or power has a 'positive' function of increasing that capability. In presenting these estimates, we make use of the following abbreviations: 17 R R D is the rank of is the rank of is the political sender and the SI is the sincerity I is the intensity SA is the saliency the receiver k is a constant 8 r the sender the receiver distance between the receiver of the b l a m e of the b l a m e of t h e g i v e n issue(s) to After this I may present the estimate for the capability of blaming (C) as and blame effect (E) as The more precise measure of rank, intensity, sincerity, and saliency will not be dealt with in any detail in this context. Measures for ranking nations are relatively many and well developed. In a formal measure of intensity in addition to formal quantitative expressions for volume, support and scope, one of course will have to include a figure representing the position of the blame according to the blame scale I developed. Sincerity may be defined as ranging between 0 as minimum and 1 as maximum sincerity. Political distance, however, should be explained in some detail. I propose that it is measured by UN voting behavior over the period of one year because this is probably the best indicator of a general political attitude or opinion position developed so far, and because the USAUSSR continuum has been used by several authors already. The scale of political distance could of course be categorized in different ways and by more variables than the UN voting behavior. Clustering according to this variable might be used in the sense that the clusters one finds are taken as categories in the general scale. But such voting clusters may and do change over time; what we need then is both adjustments of the scale, but also some sort of a more durable category set. In Figure 1, a scale of seven categories is constructed and each category described (the end-points are not counted as categories). The scale may be used in the USSR-USA relationship, but could also have a more general application for systems which are more or less polar18 19 20 'Blame' as International Behavior ized between two relatively equally powerful actors. By counting the number of categories between the sender and the receiver, one gets the generalized political distance between them. 6. Blame and the international system Blame behavior activity may and should of course also be related to political distance in any sender-receiver relationship, i.e. a system of any two actors. This would in fact be necessary in order to register all acts of blame behavior in the total system. Such behavior in a dyad may then be correlated with the rank distance and the political distance between the two actor components. Concerning rank distance, my hypothesis would be: Blame behavior activity tends to be positively correlated with rank distance in the sense that the high ranking will blame the low ranking more than vice-versa. This would be in accordance with topdog-underdog interaction on other dimensions. The relationship between political distance seems more problematic. A common sense hypothesis would be that blame behavior activity increases with increasing political distance: the greater the distance the less danger there is for counter-blame or other measures from the receiver. On the other hand, as has been pointed out, the blame sent from a great political distance tends to be perceived as insincere and thus ineffective. Thus, it seems that the most interesting blame behavior - and perhaps the most active, since actors at great 21 59 distance, knowing that their blame is perceived as mostly 'ritualistic', will probably tend not to be such active blamers as would be expected - occurs at some crucial 'middle political distance'. Political distance may also be related to the integration-disintegration dichotomy. Blame sent between actors at great political distance will not have any great effect, since the system in this case will be rather disintegrated in advance. Non-blaming within such a system over a considerable period of time, on the other hand, may have an integrative effect. When blame occurs between actors not far from each other in political distance however, it will most often have a disintegrative effect on the relationship between them. Correspondingly, a lasting situation of non-blaming between two actors at close political distance will have an integrative effect, possibly to the extent of making them one single actor. I have not considered drawing in geographical distance. This is due to the impression that geographical distance is not among the important factors for this kind of interaction, or that at least it is of decreasing importance. On the other hand, research has shown that geographical distance in the particular sense of sharing borders is the one relatively important variable for explaining violent conflict behavior. This dimension then and its possible role in this context should perhaps be considered. It might be that the blaming of a 22 60 Helge Hveem neighbor in some important respects is the most effective and the most fatal kind of blaming. If we now consider the global system, where the USA-USSR continuum is used as the main axis, we may make a diachronic analysis which may give us some insight into the functions of blame and its relationship to other forms of behavior. The acts of blaming which have occurred in the relationship of every single actor with each of the two super-powers may then be analyzed and possible causal relationships may also be studied by correcting for or drawing in major events, such as those already mentioned: the US Vietnam intervention, and the Soviet Czechoslovakian intervention. The plotting in or the clustering of the other actors will result in the picture of system changes indicated in Figure 2. The idea is that the Figure in some rough way gives a combined expression to the effects of blaming communicated from other actors to each one of the two super-powers when both political distance and rank are taken into consideration. The time points chosen are arbitrary and may be changed. The line drawn is of course highly tentative and would indicate the average position of the totality of actors minus the two (n - 2). This in turn is an indication of whether the system at any time point is in equilibrium or not (as measured by this single dimension). I think it is fairly correct to assume that the average over time will be somewhat to the US side of the zero line taking the Western domination of the world system into consideration. Our choice of events or concrete issues as a reference for blaming of course is not the only way of looking at it, although many actors probably do look at it in that way. There is also the deliberately chosen symmetrical outlook F i g . 2. A tentative assessment of the position of the blame balance point of the universal system over time T h e u n b r o k e n line drawn will represent the average position of the n - 2 actors in the system, vis a vis the t w o super-powers. as the platform to 'start with'; the obvious case would be the Gandhi or Nkrumah type of neutralism which makes evaluations of the super-powers based on symmetry (they are basically equally good or bad) the point of departure. This kind of analysis should evidently be compared with analyses carried out on other types of data but with the use of very much the same behavioral and structural dimensions. This would shed more light on the questions of the fruitfulness of the theory or approach I have outlined, but could also show interesting relations between the dimensions which have interested us here, and other dimensions. Some fundamental questions could be answered, e.g.: Is there a right of free speech, of free criticism, in the society of national actors? To the extent that concrete and identifiable events - acts performed by identifiable actors - are the basis of blaming, the reference of evaluation, we need some kind of a scaling of types of acts according to what blame intensity they 'deserve'. This could for instance show 23 'Blame' as International Behavior us whether or not it is so that big actors get less blame than they deserve, small more. But this is back to the problem of the lack of universal norm systems mentioned above. I shall not go into this problem here. One should, as already indicated, study the role of blame and praise within different systems: the global super-power oriented system, the international multi-actor sub-systems, and the two-actor systems. The question of possible correlations with other forms of behavior or interaction should be studied to get an overall picture of the network of interactions or exchanges in the system, the relations between affective (blaming) and utilitarian (trading) behavior, between different types of affective behavior, etc. 7. The balance of blame The problem of the equilibrium of any given system poses certain questions. How long can a system bear a heavy blame volume from actors with high capability and with the probability of great effect placed on one or more of its important (or system-dominant) actors without being changed? How long can any one actor, not very high in rank and with relatively low blame tolerance, stand up against heavy blaming from a number of other actors, among them the more important, without losing position? The first question raises another more concrete or specific question: how long could the US leadership have stood unaffected by outside blaming, keeping up with its Vietnam policy and generally pursuing the role of a 'policeman' in the third world? And when at the same time the Soviet Union's general image became more and more of the Tashkent peace-maker outlook - how long could the global system (and sub-systems) have been unaffected by this develop24 61 ment, in the sense that its equilibrium would not have been changed? There are several answers to these and related questions. USA may be said to be able to stand all the blaming she could get through her vast resources. And due to the (contended) fact that the system's equilibrium or balance has usually tended to be very much in her favor, she could take the risk of losing some of her position throughout the world without seeing the balance - one might call it the 'moral balance' - tip in favor of the other party. Now the problem does not seem acute: USSR solved it in Czechoslovakia. France of the Fourth and the beginning of the Fifth Republic would be an example of the not-so-high in rank and the low-tolerance actor which could not in the long run stand up against heavy blaming from outside. Evidently it was not only, perhaps not first of all, the fact that she was blamed for her colonial policies which made her withdraw from Indochina and Algeria: she was to a large extent forced out. But blaming seems to have played an important role. The more so perhaps in the case of Suez 1956, where the three aggressors had to withdraw exceptionally quickly having received heavy blaming from both friends and foes. This is the case where the two super-powers join in blaming some third party. In that case the probability that an actor could stand the blaming without being affected is relatively low and it becomes perhaps more remote the lower that actor is in rank. When the two great super-powers join, there is an informal and inapplicable High Court (or perhaps rather police magistrate) decision. The world has its enfants terribles or outcasts - the actors blamed by all or most of the other actors at some time. They are middle-range or small actors; the great power being an outcast is 62 Helge Hveem rather improbable, unless having lost a war, i.e. Germany, after the First and Second, and Japan after the Second World War. The obvious examples are South Africa and Portugal. Why is it that these actors, in spite of the relatively heavy blaming volume they are subject to, do not change their policies - why does blame not seem to have any effect upon them? One reason would be their high blame tolerance, their authoritarian regimes, their will or fanaticism, or their value systems which seem to be rather different from those of most other actors. But it is probably as likely that the explanation for the lack of evident effect is their affiliations with important actors, i.e. the Western great powers: the blaming of these actors is both moderate and - more important - has a very low credibility, because of the other kinds of relationships which they keep with the two outcasts. Perhaps one important function of the blaming of such outcasts is that it may be used to cement or hold together a difficult and at the same time much needed unity of the senders (the black African blaming of the white Southern African is probably one case in point). The lesson to be drawn from our discussion of the effects of blaming on an international system, especially its disequilibrating effect, would logically be that to keep the necessary equilibrium and symmetry, blame has to be distributed evenly at least between the dominant actors of that system. This point is touching a much-used and much disputed rule in Norwegian political debates: when blaming the Soviet Union (or USA) one should not forget the other party's or side's bad acts; when criticizing USA policy in Vietnam one should not forget Soviet policies in Eastern Europe. Quid pro quo at any time point! This might be said to be a rather conservative, non-dynamic view which seems to restrict somewhat the intensity of blame which it may seem fair to send on isolated time-points or on specific events. Nevertheless, it seems to be one of the informal international rules actually working. And the actors in question have usually been able to solve the problem themselves by in fact showing that blame 'deserved' may be distributed relatively evenly. Or, they have been able to control blame, particularly from those actors which stand relatively close to themselves (which fall within their respective 'spheres of influence'). The dominant actors may point to the danger implied in their being intensely blamed by 'their own friends': this will tip the balance in the favor of some other dominant actor and thus threaten the senders themselves. Or, the dominant actor may only point to the duty of close allies of not behaving disloyally towards their defensor (if military relations are important) or benefactor (if financial aid is important). Or, he may simply point to the necessity of maintaining internal consensus, including non-blaming, within the sub-system, as an aim in itself, or which is perhaps as likely the case - in order that the dominant actor within that sub-system will be able to maintain its dominance. An empirical point of reference would be the last Communist world conference, where the invasion of Czechoslovakia was criticized by some of the delegations, and where the Soviet Union, moreover, tried without being particularly successful, to get the conference to put the blame for the Sino-Soviet border disputes on China. In such cases, non-blaming becomes the interesting type of behavior. On a lower level, there is the equilibrium problem in the relations between two actors. The one may feel that the 'Blame' as International Behavior other is blaming him so much (more than he himself blames the other) that he has to retort, either by blaming or by other means, just to keep some kind of an equilibrium between them, so that the other does not get a permanent 'moral superiority' or political grip on him. Or, one may have the case where an actor starts blaming another actor, or 'over-blaming' him (blaming him more than he objectively or relatively deserves) just to compensate for that other actor's superiority over himself or possibly grip on him on other dimensions. The case of Guinea, which has been heavily blaming the USA for some years while at the same time getting more aid and investments from that country than from any other country (including the Soviet Union, which on the contrary has been very much praised by Guinea) might be an example of this kind of relation. Of course it may also be explained by the deliberate policy of USA in this case not to let the fact of being blamed by the recipient make it cease giving aid to i t . It may want to give it for other reasons. 63 presented in a complete matrix. Such a matrix could cover both measures of blaming effect and blaming capability and measures of actual blaming behavior over a certain time period. Fig. 3 below may explain the point. Fig. 3. The matrix for presenting blaming capability, blaming effect and actual blaming behavior: the case of blaming capability One rubric contains measures for the sender-receiver relation, as follows: 25 26 8. The system as a field: a note on the methodology Instead of the linear model which has been used so far, one should consider using the sociogrammatic method, which in many concrete international systems would seem to tap more of reality than the linear method. Moreover, it may better visualize my theory. Before discussing this point, we should make it clear that the method of data collection of course would have to include some ways of assessing the blamepraise relations in any pair of actors in the system. This must be done by the use of the variables we have discussed, by operationalizing them for quantitative analysis, and the results may be A similar matrix would then have to be worked out for the case of blaming effect, with information on the E , Eb etc. estimates and the blame received by the various actors from all other actors. One step in the direction of improvement of the linear model would be to make use of the geometric matrix, while keeping the bipolar structure with two dominant actors as checking points. The less dominant or non-dominant actors are plotted in relative to the two points, but in the field; this is tentatively shown in Figure 4. This graph is in some ways more representative of the concrete international system. But it still does not satisfactorily deal with the recent developments toward some degree of multipolarity, e.g. a 64 Fig. Helge Hveem 4. A field (geometric) relationships model of blaming toward more than two dominant actors. The very fact that Communist China is not a member of the UN points to one important argument against using the data from the UN voting studies as a basis for the construction of political distance. And the emergence of China - however much disputed - as a third super power also speaks against the bipolar model. It may also be argued that the position of gaullistic France would be difficult to catch, even in the model we have shown in Figure 4. The logical thing then would be to construct a third model based on three or four dominant actors. But this raises serious problems and, especially in the case of a system of a greater number of actors, might be quite impossible. If we chose three dominant actors and set out to assess the position of the other actors relative to the three, we might see that there is not one single point which might represent the position of the actor in question relative to all three. What we, at the most would get, is some rough assessment of an area within which the actor in question would be found. We should probably have to construct a cube to cope with this, but even that would not be satisfactory. And in the case of four dominant actors, it seems quite impossible to construct any model which could be used to visualize the system. NOTES * This is a first draft paper. I am indebted to Professor Johan G a l t u n g a n d to t h e staff of the International P e a c e R e s e a r c h Institute, O s l o , particularly N i l s Petter G l e d i t s c h and Kjell Skjelsbaek for v a l u a b l e c o m m e n t s on the paper a n d the ideas presented. It c a n be identified as PRIO-publication 2 0 - 9 . 1 Robert C. N o r t h , O l e R. Holsti, M. G e o r g e Z a n i n o v i c h , a n d D i n a A. Z i n n e s , Content Analysis. A Handbook with Applications for the Study of International Relations Crisis (Evanston: N o r t h w e s t e r n U n i v e r s i t y Press, 1963) p. 147. I am particularly thinking of t h e leading countries of the ' B a n d o e n g group', such as U n i t e d A r a b Republic, Y u g o s l a v i a , India. T h a t t h e result in t h e l o n g run of this b l a m i n g actually m a y be said to be quite the c o n trary is another thing. T h e b l a m i n g reached a 'peak' w h e n o n e of the t h e n leading m e m b e r s of t h e S w e d i s h government, Mr. Olof P a l m e , n o w P r i m e Minister of S w e d e n , participated in a d e m o n s t r a t i o n i n S t o c k h o l m against the U S p o l i c y i n V i e t n a m a n d t o t h e support o f N o r t h V i e t n a m . T h e U S g o v e r n m e n t recalled t h e U S a m b a s s a d o r t o S w e d e n a n d for s o m e t i m e there w e r e rather bad relations b e t w e e n the t w o countries. O n e of the m a i n lines of t h o u g h t b e h i n d t h e A m e r i c a n behavior towards the S w e d i s h b l a m e s e e m s to h a v e b e e n that they e x p e c t e d a declared neutral or non-aligned country like S w e d e n not to take sides in controversial international disputes. This v i e w w a s strongly rejected by the S w e d i s h g o v e r n m e n t w h i c h m a i n t a i n e d its right to criticize w h e n e v e r a n d w h o e v e r it f o u n d it correct to criticize. T h u s , it t o o k t h e p o s i t i o n of 'active neutralism'. Cf. N o r t h et al., op cit.; R u d o l p h J. R u m m e l , ' D i m e n s i o n s of Conflict B e h a v i o r w i t h i n and b e t w e e n N a t i o n s ' , General Systems: Yearbook of the Society for General Systems Research, 2 3 4 6 'Blame' as International Behavior 65 V I I I (1963), p p . 1-50; C h a r l e s M c C l e l l a n d , 'Access to Berlin: T h e Quantity a n d Variety of E v e n t s , 1 9 4 8 - 1 9 6 3 ' , in J. D a v i d Singer (ed.), Quantitative International Politics: Insights and E v i d e n c e ( N e w Y o r k : T h e F r e e Press, 1967), pp. 1 5 9 - 8 6 . F o r instance, there m a y be situations w h e r e praise is a f o r m of conflict behavior, and correspondingly w h e r e b l a m e is n o n - c o n f l i c t behavior. B l a m e at least m a y h a v e the effect of creating interaction w h e r e such did not exist, giving it a positive function in that respect. Cf. H a r o l d N i c o l s o n , Diplomacy ( L o n d o n : O x f o r d U n i v e r s i t y Press, 1963, 3rd ed.). R u d o l p h J. R u m m e l , 'A Social F i e l d of Conflict Behavior', Peace Research Society: Papers, IV, C r a c o w Conference, 1965; D i n a A . Z i n n e s , ' T h e E x p r e s s i o n and Perception o f Hostility in Prewar Crisis: 1914', in J. D a v i d Singer (ed.), o p . cit. p p . 8 5 - 1 1 9 ; M c C l e l l a n d , o p . cit.; W a y n e R . Martin a n d R o b e r t A . Y o u n g , 'World Event-Interaction Study: P i l o t Study Report' (University of M i c h i g a n , 1966) m i m e o . T h e scales they p r o p o s e are: 6 7 8 Rummel Zinnes 1. Shirking 2. N e g a t i v e sanctions 2. 3. E x p e l or recall a m b a s s a d o r 3. 4. E x p e l or recall l o w e r rank 5. Severance of diplomatic rela- 4. tions 5. 6. A c c u s a t i o n s 6. 7. Protests 7. 8. Threats 8. 9. Mobilizations 10. T r o o p 9. movements 10. 11. Military a c t i o n 11. 12. W a r 12. Martin I II III IV V VI VII VIII and Young, McClelland 1. A c c e d e Withdraw Preventing press f r o m 2. R e q u e s t m i s l e a d i n g public o p i n i o n 3. P r o p o s e U s i n g events against 4. Bargain opponent Convey C o o l relationship 5. A b s t a i n Tolerating agitation against Protest others 6. Reject Deny R e p r o a c h i n g the other 7. A c c u s e Conspiracy 8. D e m a n d M a k i n g d e m a n d s , diplomatic 9. W a r n rupture Threaten Getting m a x i m u m 10. D e c r e e Mobilization 11. D e m o n s t r a t e D e c l a r a t i o n of w a r 12. F o r c e 13. Attack Destruction 1. A n t i - f o r e i g n demonstrations collapsed obligations categories: Withdraw Collaborate Bargain (mild): question, request, p r o p o s e Bargain ( m e d i u m ) : accuse, c o m p l a i n Bargain (defend): deny, reject Bargain (strong): w a r n , threaten, d e m a n d P u n i s h : break relationship, expel C o e r c e : seize, f o r c e 9 H e r m a n K a h n , On Escalation: Metaphors and Scenarios, T h e H u d s o n Institute, 1965. K a h n has 44 'steps' in his ladder, ranging f r o m 'Ostensible crisis' to 'Spasm or insensate war'. Charles A . M c C l e l l a n d , ' A P r o p o s a l t o M e a s u r e a n d A n a l y z e O p p o s i t i o n and Threat A c tions of Other Countries directed t o w a r d U n i t e d States' Policies A b r o a d ' , D e p a r t m e n t of Political Science, University of M i c h i g a n , January 1967 ( m i m e o ) . T o m e n t i o n o n e e x a m p l e only, n o t w h o l l y i n t o the ' R u m m e l school', cf. N i l s Petter G l e ditsch, 'Rank T h e o r y , F i e l d T h e o r y and Attributive T h e o r y : T h r e e A p p r o a c h e s t o International Behavior', paper written f o r t h e C o n f e r e n c e of secondary data analysis, Institut für vergleic h e n d e Sozialforschung, C o l o g n e . I a m particularly thinking o f t h e affirmations o f t h e U S g o v e r n m e n t o n t h e e v e o f the i n v a s i o n that s o m e of t h e major issues, such as negotiations on disarmament and reduction o n the anti-missile programs, w o u l d n o t b e affected b y t h e invasion. T h i s o f c o u r s e m a y b e d u e t o other factors a n d the s a m e w o u l d b e true i n the c a s e w h e r e 10 11 12 13 5 Journal of Peace Research 66 Helge Hveem the Soviet U n i o n d o e s m a k e a c h a n g e in its policy, w h i c h d o e s not s e e m v e r y likely and which will not be discussed here. A s R u m m e l s h o w s , 'rank distance' i s h i g h l y correlated with 'power distance', and i n this context the t w o c o n c e p t s are seen as m o s t l y s y n o n y m o u s . Cf. R u m m e l , 'A Social F i e l d of Conflict Behavior'. Our c o n c e p t i s n o t dissimilar t o t h e c o n c e p t u s e d b y R u m m e l - 'value distance', w h i c h i n his terminology m e a n s 'the existence of m u t u a l l y i n c o m p a t i b l e or contradictory g o a l s or values', cf. ibid. This p o s i t i o n i n further c o n f i r m e d b y t h e findings o f Martin a n d Y o u n g , o p . cit. w h e r e they find that the U n i t e d States a n d the S o v i e t U n i o n (in that order) are t h e m o s t active senders of blame-related acts and the highest-ranking receivers. T h e s e relations, a t least until very recently, h a v e n o t b e e n characterized b y small political distance b e t w e e n the t w o . T h u s , the 'Western sub-system' h a s u n d e r g o n e s o m e c h a n g e since the first m o d e r a t e v o i c e s of disapproval or criticism occurred in F r a n c e in the m i d d l e of the 1950's. See for instance Johan G a l t u n g , M a n u e l M o r a y A r a u j o and S i m o n Schwartzmann, "The Latin-American System of N a t i o n s : A Structural Analysis'. T h e reason f o r n o t m a k i n g this variable c o u n t stronger is simply the impression that it is not so important or so potentially effective, especially as third parties, w h o s e evaluations m o s t often c o m e into t h e picture rather strongly m a y b e expected n o t t o p l a c e s o m u c h weight o n this variable as for instance t h e receiver. Cf. H a y w a r d A l k e r jr. a n d B r u c e M. Russett, World Politics in the General Assembly ( N e w H a v e n : Y a l e University Press, 1965). Johan Galtung, 'East-West Interaction Patterns', Journal of Peace Research, n o . 2, 1966, pp. 146-77. Cf. R u d o l p h J . R u m m e l , "The R e l a t i o n s h i p b e t w e e n N a t i o n a l Attributes a n d F o r e i g n C o n flict Behavior', in J. D a v i d Singer (ed.), o p . cit., pp. 1 8 7 - 2 1 4 . T o s o m e extent, neutralism o f c o u r s e i s a l s o a reaction t o events d u e t o the likely discovery that b o t h sides h a v e b e h a v e d badly or nicely. T h e inside, d o m e s t i c A m e r i c a n blaming o f t h e p o l i c y i n V i e t n a m n o d o u b t has p l a y e d a n important, perhaps m o r e important r o l e in that respect. Guinea's trade (in 1966) w a s distributed, a m o n g its principal trading partners, a s f o l l o w s : 14 15 18 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 Imports U n i t e d States Soviet U n i o n China Ex ports 2.5 billion G . F r . 1.3 1.1 - France U n i t e d States 2.5 billion G. F r . 1.8 - 26 Cases such a s G u i n e a h a v e raised m u c h criticism o f the U S f o r e i g n aid p r o g r a m i n C o n gress. T h e a r g u m e n t h a s b e e n that t h e U n i t e d States s h o u l d n o t trade extensively with nor extend aid a n d technical assistance t o countries w h i c h b e h a v e unfriendly towards the U n i t e d States. Such criticism h a s p r o b a b l y contributed m u c h to t h e reduction in recent years of U S assistance t o the d e v e l o p i n g countries. SUMMARY This article presents a d i m e n s i o n of state b e h a v i o r w h i c h it p r o p o s e s h a s theoretical and practical relevance to a t h e o r y of conflict, a t h e o r y of sanctions, a n d generally to theories of inter-state interaction. Being primarily theoretical, the article discusses t h e r o l e of 'blame' in international politics, b o t h as an isolated pattern of b e h a v i o r , a n d in c o n n e c t i o n with other patterns of behavior. 'Blame' is seen as n o n - v i o l e n t , conflict behavior. It is related to the stratification of international systems, and to t h e c o n c e p t of political distance b e t w e e n t w o actors. Scales and estimates f o r measuring b l a m e , b o t h f r o m t h e sender's a n d t h e receiver's point of view, are presented, a n d a discussion of m e t h o d o l o g i c a l p r o b l e m s i n v o l v e d in an empirical test of t h e theory p r o p o s e d , is m a d e at the end. 'Blame' as International Behavior 67