Synthetic Lethality — A New Direction in Cancer-Drug Development

advertisement

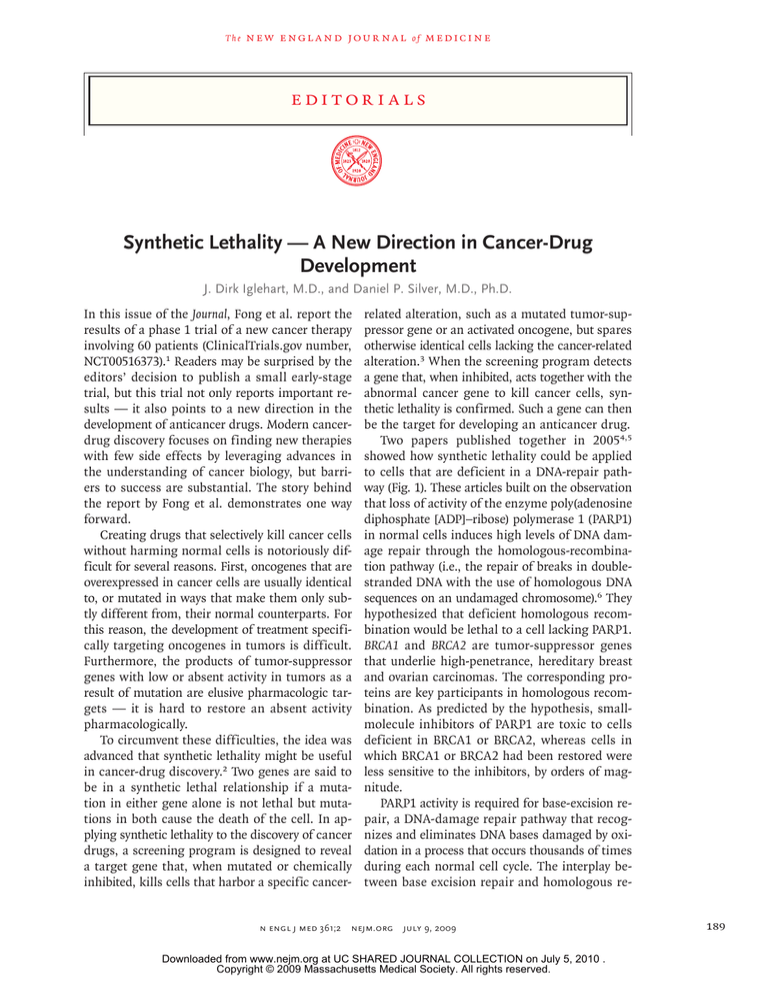

The n e w e ng l a n d j o u r na l of m e dic i n e edi t or i a l s Synthetic Lethality — A New Direction in Cancer-Drug Development J. Dirk Iglehart, M.D., and Daniel P. Silver, M.D., Ph.D. In this issue of the Journal, Fong et al. report the results of a phase 1 trial of a new cancer therapy involving 60 patients (ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT00516373).1 Readers may be surprised by the editors’ decision to publish a small early-stage trial, but this trial not only reports important results — it also points to a new direction in the development of anticancer drugs. Modern cancerdrug discovery focuses on finding new therapies with few side effects by leveraging advances in the understanding of cancer biology, but barriers to success are substantial. The story behind the report by Fong et al. demonstrates one way forward. Creating drugs that selectively kill cancer cells without harming normal cells is notoriously difficult for several reasons. First, oncogenes that are overexpressed in cancer cells are usually identical to, or mutated in ways that make them only subtly different from, their normal counterparts. For this reason, the development of treatment specifically targeting oncogenes in tumors is difficult. Furthermore, the products of tumor-suppressor genes with low or absent activity in tumors as a result of mutation are elusive pharmacologic targets — it is hard to restore an absent activity pharmacologically. To circumvent these difficulties, the idea was advanced that synthetic lethality might be useful in cancer-drug discovery.2 Two genes are said to be in a synthetic lethal relationship if a mutation in either gene alone is not lethal but mutations in both cause the death of the cell. In applying synthetic lethality to the discovery of cancer drugs, a screening program is designed to reveal a target gene that, when mutated or chemically inhibited, kills cells that harbor a specific cancer- related alteration, such as a mutated tumor-suppressor gene or an activated oncogene, but spares otherwise identical cells lacking the cancer-related alteration.3 When the screening program detects a gene that, when inhibited, acts together with the abnormal cancer gene to kill cancer cells, synthetic lethality is confirmed. Such a gene can then be the target for developing an anticancer drug. Two papers published together in 20054,5 showed how synthetic lethality could be applied to cells that are deficient in a DNA-repair pathway (Fig. 1). These articles built on the observation that loss of activity of the enzyme poly(adenosine diphosphate [ADP]–ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP1) in normal cells induces high levels of DNA damage repair through the homologous-recombination pathway (i.e., the repair of breaks in doublestranded DNA with the use of homologous DNA sequences on an undamaged chromosome).6 They hypothesized that deficient homologous recombination would be lethal to a cell lacking PARP1. BRCA1 and BRCA2 are tumor-suppressor genes that underlie high-penetrance, hereditary breast and ovarian carcinomas. The corresponding proteins are key participants in homologous recombination. As predicted by the hypothesis, smallmolecule inhibitors of PARP1 are toxic to cells deficient in BRCA1 or BRCA2, whereas cells in which BRCA1 or BRCA2 had been restored were less sensitive to the inhibitors, by orders of magnitude. PARP1 activity is required for base-excision repair, a DNA-damage repair pathway that recognizes and eliminates DNA bases damaged by oxidation in a process that occurs thousands of times during each normal cell cycle. The interplay between base excision repair and homologous re- n engl j med 361;2 nejm.org july 9, 2009 Downloaded from www.nejm.org at UC SHARED JOURNAL COLLECTION on July 5, 2010 . Copyright © 2009 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved. 189 The A Normal Cells Base-excision repair B Homologous recombination PARP1 BRCA n e w e ng l a n d j o u r na l Cells with BRCA Mutation Base-excision repair Homologous recombination PARP1 BRCA X C of m e dic i n e Cells with Drug-Induced PARP1 Inhibition Base-excision repair PARP1 Cancer drug Homologous recombination BRCA D Cells with BRCA Mutation and PARP1 Inhibition Base-excision repair Cancer drug Homologous recombination BRCA X PARP1 No repair Repair Repair Repair Cell death Figure 1. Mechanism of Cell Death from Synthetic Lethality, as Induced by Inhibition of Poly(Adenosine Diphosphate [ADP]–Ribose) Polymerase 1 (PARP1). In normal cells, both base-excision repair and homologous recombination are available for the repair of damaged DNA (Panel A). In cells that have lost either BRCA1 or BRCA2 (e.g., cancer cells in carriers of a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation), homologous recombination is nonfunctional, and base-excision repair and other DNA-repair processes can compensate for the loss of homologous recombination (Panel B). In cells that have lost base-excision repair function because of PARP1 inhibition but retain at least one functioning copy of BRCA1 and BRCA2 (e.g., normal cells in carriers of a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation), homologous recombination is intact and can repair DNA damage, including damage left unrepaired because of the loss of base-excision repair (Panel C). In the cancer cells of mutation carriers, all BRCA1 or BRCA2 function is absent, and when PARP1 is inhibited, cancer cells are unable to repair DNA damage by homologous recombination or base-excision repair, and cell death results. combination may occur indirectly: in the absence of PARP1, oxidized bases accumulate, and replication forks, where DNA strands are being replicated during DNA synthesis and two new DNA strands are being created, are arrested at sites of the damaged DNA, eventually causing double-strand DNA breaks. Normally, homologous recombination repairs these breaks, but should this mechanism be unavailable, as is the case when BRCA1 or BRCA2 is absent, the cell dies. Screening programs for other genes required to maintain cell viability in the absence of PARP1 activity support our understanding of the mechanism of the synthetic lethality resulting from PARP1 inhibition and BRCA1 or BRCA2 loss. These experiments have uncovered a number of genes required for homologous recombination that are synthetically lethal when combined with PARP inhibition.7 Genes required for other DNArepair processes are also in a synthetic lethal relationship with PARP inhibition,8 most likely because of the partially redundant nature of these processes. Furthermore, some checkpoint genes are synthetically lethal in combination with PARP inhibition, suggesting that normal checkpoint function (cell-cycle arrest caused by DNA damage) is critical to allow for time to repair DNA in the absence of PARP activity.9 Patients with hereditary breast or ovarian carcinoma are perfect candidates for treatment with PARP inhibitors, since such patients are heterozygous for mutations in BRCA1 or BRCA2 and thus have preserved homologous recombination in their somatic cells, whereas their tumors have lost the remaining wild-type copy of BRCA1 or BRCA2 and are therefore deficient in homologous recombination. There are almost certainly other tumors with defects in homologous recombination that should make them targets for PARP inhibitor therapy — the challenge is to identify them. One such tumor type may be sporadic basal-like breast cancer, which has a number of similarities to BRCA1-deficient breast cancer, suggesting that it may have decreased BRCA1 levels or some other defect in the BRCA1 pathway. Cisplatin is a cytotoxic agent with some specificity against cells with defective homologous recombination; the fact that some basal-like breast cancers are sensitive to cisplatin10 indicates that they may be candidates for PARP-inhibition therapy. Version 5 06/16/09 Fong et al. demonstrated stabilization Author Iglehart or reFig # 1 gression of BRCA1- or BRCA2-defective breast, Title Synthetic Lethality COLOR FIGURE JL RSS LAM ME 190 n engl j med 361;2 nejm.org july 9, 2009 DE Artist AUTHOR PLEASE NOTE: Figure has been redrawn and type has been reset Please check carefully Issue date Downloaded from www.nejm.org at UC SHARED JOURNAL COLLECTION on July 5, 2010 . Copyright © 2009 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved. 07/09/09 editorials ovarian, and prostate cancers in response to an oral PARP inhibitor; no activity was seen outside BRCA1- or BRCA2-defective tumors.1 This observation should not discourage a search for other tumor types with vulnerability to PARP inhibition; the number of patients in this trial is too small to draw any conclusions about other cancers. Basal-like breast cancer, for example, accounts for approximately 15% of all breast cancer, and it is entirely possible that with just six cases of non-BRCA1 or non-BRCA2 breast cancer in this study, no tumors of this subtype were represented. New therapies bring new challenges into focus, and PARP inhibitors will be no exception. Resistance to cisplatin and related compounds in ovarian cancer arising in carriers of mutant BRCA1 or BRCA2 can be caused by reversion of the mutated BRCA1 or BRCA2 allele, thereby restoring homologous recombination. In addition, BRCA2 reversion in cell culture causes resistance to PARP inhibition.11-13 These findings strongly suggest that PARP inhibition alone may not be sufficient to control metastatic disease. Now that we have treatments that target a specific molecule, we can see in sharp focus the mechanisms of tumor escape. It is possible that conventional therapies fail in much the same manner, but since their targets are usually unclear, the molecular details of resistance are often hard to discern. Optimal treatment may require approaches to reduce the genetic complexity of a tumor and avert the emergence of resistance, such as concurrent use of multiple therapies that do not share resistance mechanisms, or debulking to the maximum extent possible by means of surgery or conventional therapies before a targeted agent is used. No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported. From the Department of Surgery, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and the Department of Cancer Biology, Dana–Farber Cancer Institute (J.D.I.); and the Department of Medical Oncology, Dana–Farber Cancer Institute, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School (D.P.S.) — all in Boston. This article (10.1056/NEJMe0903044) was published on June 24, 2009, at NEJM.org. 1. Fong PC, Boss DS, Yap TA, et al. Inhibition of poly(ADP- ribose) polymerase in tumors from BRCA mutation carriers. N Engl J Med 2009;361:123-34. 2. Hartwell LH, Szankasi P, Roberts CJ, Murray AW, Friend SH. Integrating genetic approaches into the discovery of anticancer drugs. Science 1997;278:1064-8. 3. Kaelin WG Jr. The concept of synthetic lethality in the context of anticancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2005;5:689-98. 4. Bryant HE, Schultz N, Thomas HD, et al. Specific killing of BRCA2-deficient tumours with inhibitors of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. Nature 2005;434:913-7. [Erratum, Nature 2007;447: 346.] 5. Farmer H, McCabe N, Lord CJ, et al. Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells as a therapeutic strategy. Nature 2005;434:917-21. 6. Schultz N, Lopez E, Saleh-Gohari N, Helleday T. Poly(ADPribose) polymerase (PARP-1) has a controlling role in homologous recombination. Nucleic Acids Res 2003;31:4959-64. 7. McCabe N, Turner NC, Lord CJ, et al. Deficiency in the repair of DNA damage by homologous recombination and sensitivity to poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibition. Cancer Res 2006;66: 8109-15. 8. Lord CJ, McDonald S, Swift S, Turner NC, Ashworth A. A high-throughput RNA interference screen for DNA repair determinants of PARP inhibitor sensitivity. DNA Repair (Amst) 2008;7:2010-9. 9. Turner NC, Lord CJ, Iorns E, et al. A synthetic lethal siRNA screen identifying genes mediating sensitivity to a PARP inhibitor. EMBO J 2008;27:1368-77. 10. Garber J, Richardson A, Harris L, et al. Neo-adjuvant cisplatin (CDDP) in “triple-negative” breast cancer. Presented at the 29th Annual San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium, San Antonio, TX, December 14–17, 2006. 11. Sakai W, Swisher EM, Karlan BY, et al. Secondary mutations as a mechanism of cisplatin resistance in BRCA2-mutated cancers. Nature 2008;451:1116-20. 12. Swisher EM, Sakai W, Karlan BY, Wurz K, Urban N, Taniguchi T. Secondary BRCA1 mutations in BRCA1-mutated ovarian carcinomas with platinum resistance. Cancer Res 2008;68:2581-6. 13. Edwards SL, Brough R, Lord CJ, et al. Resistance to therapy caused by intragenic deletion in BRCA2. Nature 2008;451: 1111-5. Copyright © 2009 Massachusetts Medical Society. Protecting against Future Shock — Inhalational Anthrax Gary J. Nabel, M.D., Ph.D. In a world filled with pressing unmet medical needs, why would a physician want to protect against a disease that is rarely seen? Part of the answer can be deduced from the events of the fall of 2001. The deliberate release of anthrax spores on unsuspecting U.S. citizens in the wake of September 11 unsettled Americans who were already concerned about the weaponization of smallpox, Ebola and Marburg viruses, and other pathogens. The subsequent arrival of the highly pathogenic avian influenza virus, together with the recent swine influenza epidemic, has further underscored our vulnerability to infectious diseases, both deliberate and naturally emerging. How can we face n engl j med 361;2 nejm.org july 9, 2009 Downloaded from www.nejm.org at UC SHARED JOURNAL COLLECTION on July 5, 2010 . Copyright © 2009 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved. 191