Working Paper #32 Culture Production and Social Networks

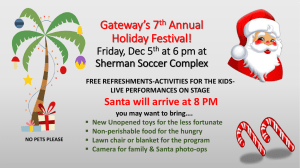

advertisement