Performance Evaluation of Safe, Productive and Infrastructure-friendly

advertisement

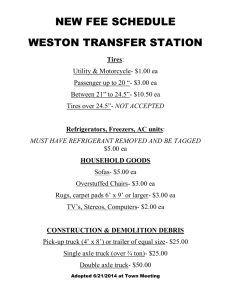

Performance Evaluation of Safe, Productive and Infrastructure-friendly Straight Trucks and Truck-trailer Combinations John R. Billing and J.D. Patten National Research Council of Canada (NRC-CSTT) INTRODUCTION R.B. Madill and A. Corredor Ontario Ministry of Transportation (MTO) TRUCK CONFIGURATIONS MTO’s reform of vehicle weights and dimensions is migrating A vehicles with liftable axles to alternative “Safe, Productive and Infrastructure-Friendly” (SPIF) configurations. BL BH C D NRC-CSTT evaluated the dynamic performance of candidate E SPIF trucks and truck-trailer combinations in support of the fourth and final phase of MTO’s regulatory development process. F A1 B1 C1 MTO identified 14 candidate SPIF straight trucks: E1 B2 C2 D2 • 7 basic configurations, A through F at right, where the self-steering pusher axle of truck D carried an equal load as each drive axle; • 4 configurations, A1 through E1, with a self-steering auxiliary pusher axle with a maximum load of 6,000 kg; and • 3 configurations, B2 through D2, with a self-steering auxiliary tag axle. TRAILER CONFIGURATIONS MTO identified 10 candidate SPIF trailers: J1 J2 J3 K L1 L2 L3 L4 M N • 4 pony (pig) trailers, J1 through K, K with a load-equalized self-steer axle; and • 6 full (dog) trailers, L1 through N, and M and N had a hinged drawbar. Trucks A, BL and A1 would pull only trailers J1, J2 and L1, while the other 11 trucks might pull any trailer, so there were 119 trucktrailer combinations to run. RESEARCH METHOD PERFORMANCE MEASURES AND STANDARDS Dynamic performance was assessed by computer simulation, using a version of the Yaw/Roll simulation program. Performance was assessed against the RTAC performance standards, and extensions and modifications thereto: A reference configuration was defined for each truck and trailer, at dimensions allowing the typical maximum gross weight. • • • • • • • • Parameter variations from the reference configuration were: • Configuration: truck front axle rating; and dimensions that affect gross weight, like wheelbase, axle spacing, axle group spread, and drawbar length for trailers L1 through L4; • Payload: weight and payload height; and for densities representing logs, grain, road salt and gravel; and • Operating conditions: any self-steering or auxiliary axle steering or locked; various loads on an auxiliary axle; with dual or wide single tires on each fixed axle; wide track drive axles on trucks; for various truck hitch offsets; for various pony trailer hitch loads; with a pintle or roll-coupled trailer hitch; with a turntable or fifth wheel on a full trailer; and for speeds of 90, 100 and 110 km/h. Low-speed offtracking < 5.60 m; Rear outswing < 0.2 m; Maximum self-steer angle; Lateral friction utilization < 0.80; Static roll threshold > 0.40 g; High-speed offtracking < 0.46 m; Load transfer ratio < 0.60; and Transient offtracking < 0.80 m. Maximum self-steer angle in a tight right-hand turn defines the selfsteer axle wheel cut required. Lateral friction utilization is the proportion of the friction from the front tire‑pavement interface necessary for the vehicle to be able to turn at an intersection on a low-friction surface. RESULTS The dynamic performance of trucks A through F, essentially depended on the weight and centre of gravity height of the payload, rather than any characteristic of the vehicle. Trucks B1, C1 and E1, with an auxiliary pusher axle, had dynamic performance similar to that of the parent configuration. Trucks B2, C2 and D2, with an auxiliary tag axle, became significantly oversteer at a lateral acceleration in the range 0.15 to 0.20 g. This is a highly undesirable handling characteristic. Truck A1, with an auxiliary pusher axle and a single drive axle, could also become oversteer, depending on the load on the auxiliary axle relative to the payload on the vehicle. The performance deficiencies of these configurations became more pronounced if they towed a trailer. Trailer L3, with a tandem axle converter dolly and a single trailer axle, failed to complete a considerable number of evasive manoeuvre runs. All other trailers exhibited high values of high-speed offtracking, load transfer ratio and transient offtracking, though the long trailer wheelbase typically needed for maximum gross weight in Ontario tended to moderate the latter two responses. The dynamic performance of all trailers depended more on the weight and centre of gravity height of the payload than any characteristic of the trailer, though the static roll threshold was invariably that of the truck, as if it was not towing a trailer. CONCLUSIONS Trucks A through F, and B1, C1 and E1, could be configured for satisfactory performance by an appropriate limit on payload, and appropriate limits on internal dimensions. Trucks B1, C1 and E1 could exist under current regulations, but are essentially unknown, so may not be more common even if allowed. Trucks A1, B2, C2 and D2 should not be considered. Trailer L3 should also not be considered. All other trailers could be configured for satisfactory performance by an appropriate limit on the trailer payload, minimum truck hitch offset, and appropriate limits on internal dimensions. STATUS MTO has published a regulatory proposal, and is engaged in consultations prior to regulation.