'176 jg J of Cambridgeg Massachusetts

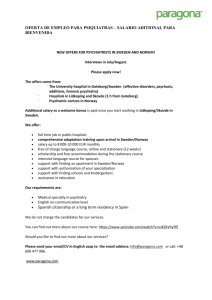

advertisement