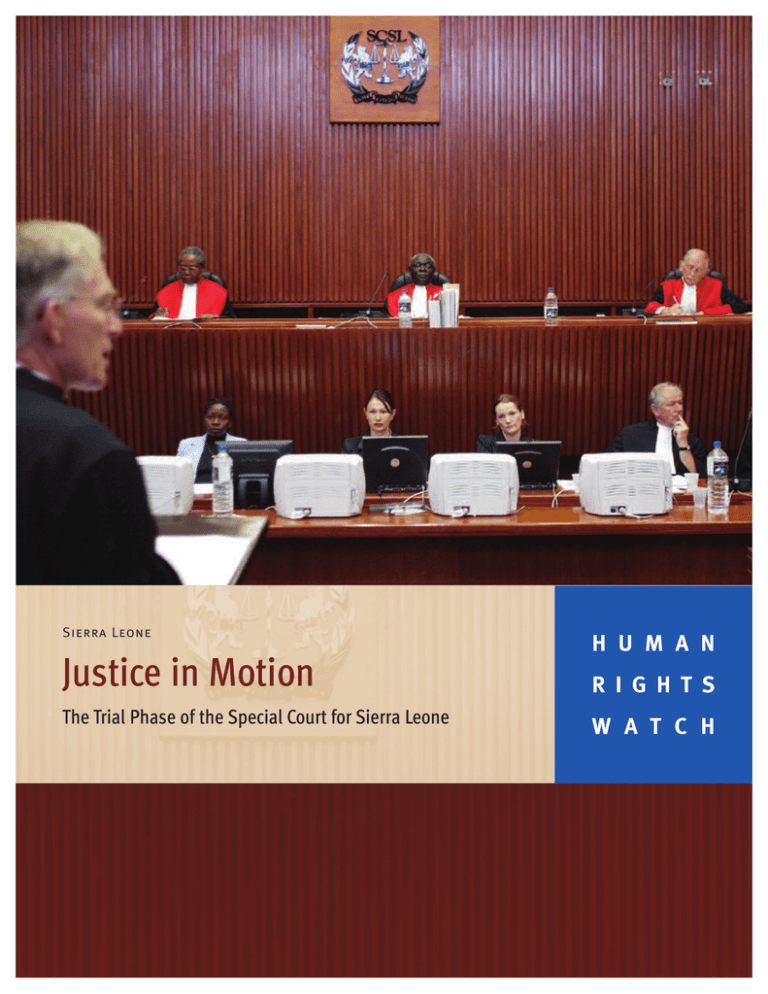

Justice in Motion H U M A N

advertisement