MITLibraries DISCLAIMER OF QUALITY

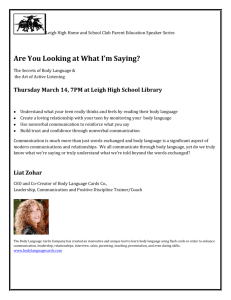

advertisement