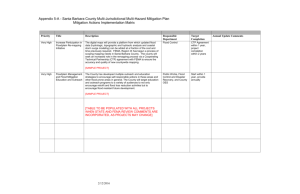

GAO FEMA FLOOD MAPS Some Standards and Processes in Place to

advertisement