GAO NUCLEAR DETECTION Domestic Nuclear

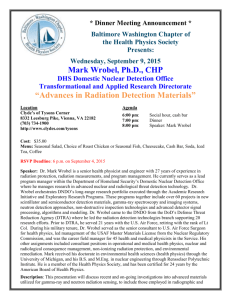

advertisement