GAO SUPPLY CHAIN SECURITY U.S. Customs and

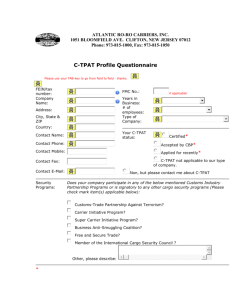

advertisement