PROCEEDINGS

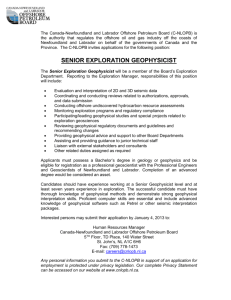

advertisement