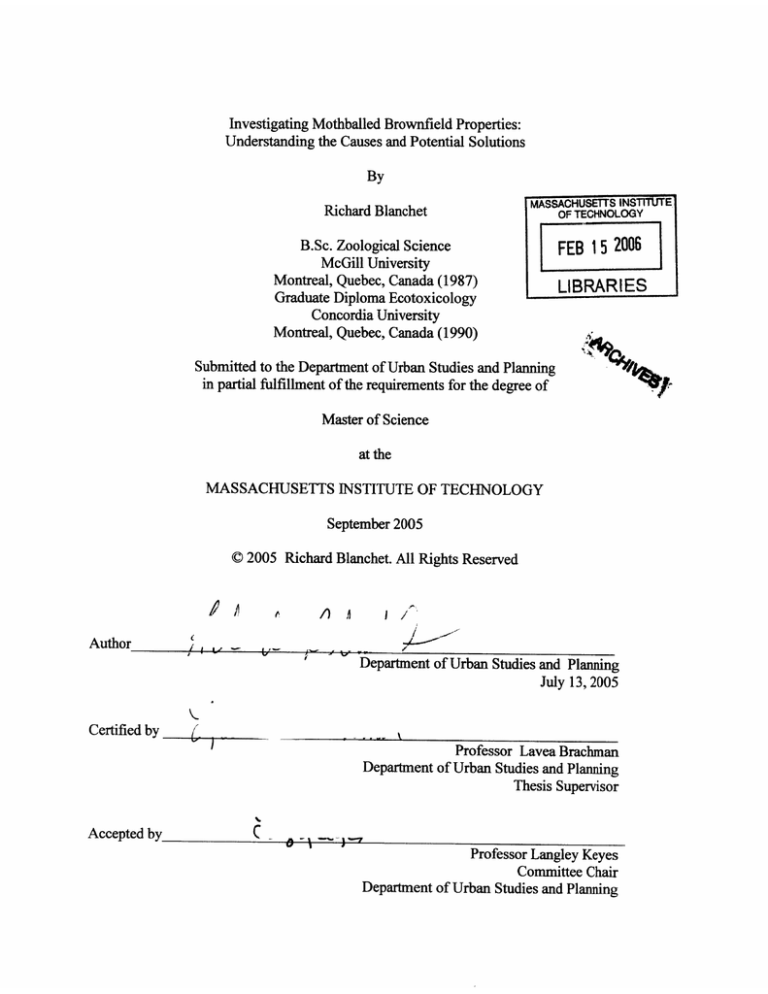

Investigating Mothballed Brownfield Properties: Understanding the Causes and Potential Solutions

advertisement