Document 11244000

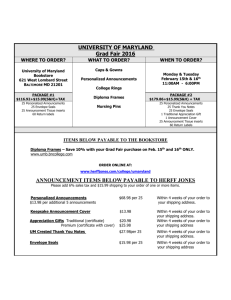

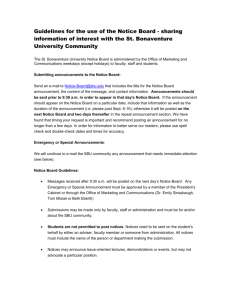

advertisement