Information, Technology, and Coordination: Lessons from the World Trade Center Response

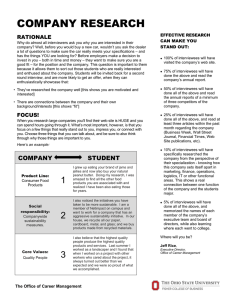

advertisement