Design of Resonant-Tunneling Diodes by Rajni J. Aggarwal

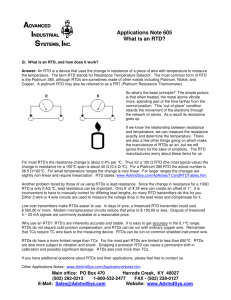

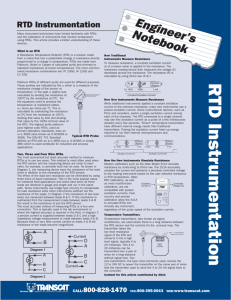

advertisement