Document 11185430

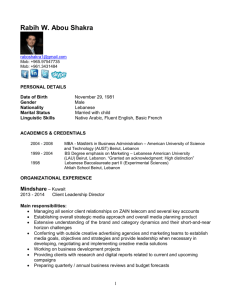

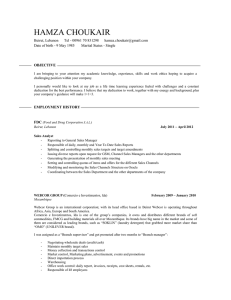

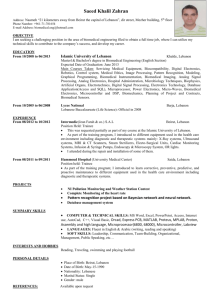

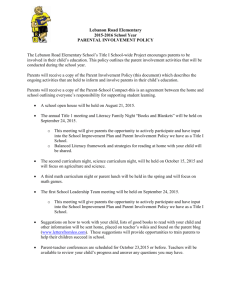

advertisement