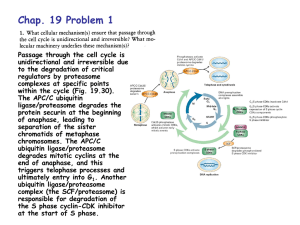

Peptide Vinyl Sulfones: Inhibitors and Active Site Probes For... Proteasome Function by Matthew Steven Bogyo

advertisement