Document 11184057

POSITIVE YOUTH DEVELOPMENT

AND CHARACTER IN ADOLESCENCE :

Understanding how youth develop to

“DO THE RIGHT THING ”

Jacqueline V. Lerner, Ph.D.

Lynch School of Education

Program in Applied Developmental Psychology

1

What We

THOUGHT

We Knew About Adolescence

• G. Stanley Hall (1904), of Clark

University, founded the study of adolescence.

• Hall defined adolescence as a period of universal and inevitable, biologicallybased “storm and stress.”

• Therefore, according to Hall, Anna

Freud, and Erik Erikson, adolescence was a period of crisis and disturbance.

• These ideas resulted in the view that adolescents were "broken" or in danger of becoming "broken."

• For almost all of the 20th century most research about adolescence was based on this deficit conception of young people.

What Research

TELLS

Us About the

Presumed “Deficits” of Youth

As early as the 1960s, research began to show that the deficit model was not in fact true:

• There are problems that occur during adolescence.

BUT there are problems that occur in infancy, childhood, and adulthood as well.

• Most young people do NOT have a stormy adolescent period.

• Although adolescents spend increasingly more time with peers than with parents, most adolescents still value their relationships with parents enormously.

• Most adolescents have core values (e.g., about the importance of education in one’s life, about social justice, and about spirituality) that are consistent with those of their parents.

• Most adolescents select friends who share these core values.

But the Deficit Models Do Not Die.

They don’t even seem to fade away…

• Throughout much of the 1990s most research continued to use

Hall’s deficit model to study adolescence.

• Literally hundreds of millions of dollars continue to be spent each year in the United States to reduce the problems “caused” by the alleged deficits of adolescents.

• These problems include

– Alcohol use and abuse

– Unsafe sex and teenage pregnancy

– School failure and drop out

– Crime and delinquency

– Depression and self-harming behaviors.

The Birth of a New Phase in the

} In the 1990s a new vision of the teen years emerged from biology and developmental science.

} This is the Positive Youth Development (PYD) perspective.

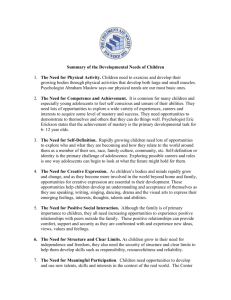

Key Principles of the PYD Perspective –Informed by

Relational Developmental Systems Theory (RDST, Lerner et al, 2005, Lerner, et al. 2013)

1.

All youth have strengths. All contexts have strengths as well. These strengths are resources that may be used to promote positive youth development. These are called

‘Developmental Assets’

2.

These assets are found in families, schools, faith institutions, youth serving organizations, and the community

3.

If the strengths of youth are combined with ecological developmental assets, then positive, healthy development may occur.

7

ALL MODELS OF THE PYD PROCESS USE

RELATIONAL DEVELOPMENTAL SYSTEMS (RDS)

THEORIES

}

}

}

The integra+on of levels of the system, from biology/physiology through culture, the physical ecology, and history

Development across life involves mutually influen+al individual !"

context rela+ons

Integrated ac+ons, individual !" context rela+ons, are the basic unit of analysis within human development

}

Time ma?ers and there is rela+ve plas+city in human development

}

Op+mism, the applica+on of developmental science, and the promo+on of posi+ve human development: The poten+al for furthering social jus+ce

DESIGN OF THE 4-H STUDY

In order to provide a new language of positive development we were asked to do a 10 year longitudinal study

The 4-H Study of Positive Youth Development

To date, we have sampled about 7,000 youth and 3,500 parents from 43 states

Ages 10-20; studied for 10 years

What factors in the person and context combine across development to promote PYD?

9

Individual

Strengths

Competence

Connec+on

PYD

Confidence

Caring Character

Ecological

Assets

Contribu+on

Reduced Risk

Behavior

10

Key Findings: Important Predictors of

PYD

INDIVIDUAL STRENGTHS:

•

Intentional Self- Regulation (ISR)

•

Hopeful Future

•

School Engagement

EXTERNAL ASSETS:

•

Institutions, families, community and faith based settings, school

•

INDIVIDUALS

•

Youth Engagement and Collective Action

•

Access

•

Contribution is a Key Outcome of PYD

•

Contribution involves Active and Engaged Citizenship

(AEC): Civic duty, Civic skills, Neighborhood social connection, and Civic participation

•

Within and across grades, Contribution is associated with ISR, Hope, and PYD

•

Lowered Risk/Problem Behaviors

•

ISR, Hope, and PYD are negatively related to Risk/

Problem Behaviors within and across grades

Digging Deeper into Character

Development in the Relational

Developmental System

Character Involves…

The acquisition of mental and behavioral attributes that develop through bidirectional feedback (Person ß à

Context Relations) between the social world and an individual’s behaviors

DEVELOPS IN CONTEXT!

What is the content of character?

•

Prior research on character has focused on content rather than on Character DEVELOPMENT

–

Moral Virtues

If we do not know how they develop we cannot promote their growth!

•

What is the content of character?

–

Performance

•

What is the content of character?

–

Intellectual

•

What is the content of character?

–

Civic

•

What is the content of character?

–

Are there other content

domains?

Contexts for Character

Development and Character

Education

How do families, schools, community programs and faith institutions foster character development in youth?

‘A virtuous person is like an expert who has highly cultivated skills– sets of procedural, declarative, and conditional knowledge– that applied appropriately in the circumstance…

Moral expertise is applying the right virtue in the right amount at the right time ’ (Narvaez, 2008, p 312 )

So…….here is the Big Question

Youth are taught right from wrong, but how do they develop a moral sense and act in accordance with it?

(and how can we explain the ‘moral gap’)

How do they learn to “DO THE

RIGHT THING?”

•

What is the structure of character?

Character

OR

Intellectual

Character

Civic Moral

Perfor-‐ mance

•

How does character develop?

What is the process of character development?

Character

Time

Some Quotes from Theorists

relations among individuals:

Individual ßà Individual relations

–

All approaches to moral and character education recognize the

Nucci & Narvaez, 2008

–

Character involves “conceptions of human welfare, justice and relations .”

Nucci, 2001

–

Character involves “a public system of universal concerns about want others to adhere to”

Berkowitz, 2012

Character Development:

Arriving at a Definition

•

Character is a specific set of mutually beneficial relations,

– between person and context, and

– between the individual and other individuals that comprise his/her context

– that vary across time and place,

–

These relations develop systematically across the life span and may be represented as individual ßà context relations

• Lerner and Callina (2014)

Character Development

Like any of the C’s of PYD, Character development occurs within a relational developmental system .

–

We need to understand what drives character development, what people, what experiences, what aspects of identity, etc.

THESE ARE THE GOALS OF MY NEW STUDY

Doing the Right Thing

•

What combines across development to promote high character?

• “ high character, virtue, or morality behave in ways that fall short of their standards?” MORAL GAP

•

Purpose: examine the role of intentional self-regulation skills and adolescents.

•

Longitudinal study of youth in the greater Boston area (Grades 6-11)

•

Data will be collected from youth and from one of their parents or guardians, and from a teacher (or other staff member) at their school who knows them well;

•

In addition, a subsample of young people will be interviewed about their perspectives on the roles of self-regulation skills and character exemplars (mentors or models) in their lives.

Key Findings: Important Predictors of

PYD- will they also predict Character?

(We just finished our pilot where we will refine our measures, etc.)

INDIVIDUAL STRENGTHS:

•

Intentional Self- Regulation (ISR)

•

Hopeful Future

•

School Engagement

EXTERNAL ASSETS:

•

Institutions, families, community and faith based settings, school

•

INDIVIDUALS

•

Youth Engagement and Collective Action

•

Access

Character

Exemplars

ISR

Moral

IdenEty

+

+

+

Youth

Virtues

Self-‐reported youth character virtues

Others’ reports of youth character virtues

+

-‐

ContribuEon

Problem

Behaviors

Conclusions and

Implications

•

Character is not fixed across time and place

– Lapsley & Narvaez; Nucci; Sokol, Hammond, & Berkowitz; Colby; Damon;

Lerner & Callina

•

Outcomes for youth can be enhanced by a focus on the youth-context relationship and building strengths

•

Self-regulation, hopeful future and role models may be essential factors in building character

Selected References

• Lerner, J. V., Phelps, E, and Forman, Y, and Bowers, E. (2009). PosiEve Youth Development.

In Handbook of Adolescent Psychology, (3 rd EdiEon). R.M. Lerner, and L. Steinberg, (Eds.),

(pps 524-‐558) New York: Wiley.

• Lewin-‐Bizan, S., Lynch, A. D., Fay, K., Schmid, K., McPherran, C., Lerner, J. V., & Lerner, R. M.

(2010). Trajectories of posiEve and negaEve behaviors from early-‐ to middle-‐adolescence.

Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39(7), 751-‐763.

• Zaff, J., Boyd, M., Li, Y., Lerner, J. V., & Lerner R. M. (2010). AcEve and engaged ciEzenship:

MulE-‐group and longitudinal factorial analysis of an integrated construct of civic engagement. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39(7), 736-‐750.

• Li, Y., Lerner, J. V., & Lerner, R. M. (2010). Personal and ecological assets and academic competence in early adolescence: The mediaEng role of school engagement. Journal of

Youth and Adolescence, 39(7), 801-‐815.

• Lerner, R. M., Lerner, J. V., Bowers, E., & Lewin-‐Bizan, S. (2012) PromoEng the posiEve development of immigrant youth: Towards an applied developmental science research agenda. In A. Masten, D. Hernandez, & K. Liebkind (Eds.), (pps 307-‐323) Capitalizing on migra>on: The poten>al of immigrant youth.

New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Selected References

• Lerner, J. V., Bowers, E. P., Minor, K., Lewin-‐Bizan, S., Boyd, M. J., Mueller, M. K., Schmid, K.

L., Napolitano, C. M., & Lerner, R. M. (2012). PosiEve youth development: Processes, philosophies, and programs. In R. M. Lerner, M. A., Easterbrooks, & J. Mistry (Eds.),

Handbook of Psychology, Volume 6: Developmental Psychology (2 nd ediEon). Editor-‐in-‐chief:

I. B. Weiner. (pp. 365-‐392). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

• Arbeit, M., Johnson, S., Greenman, K., Champine, R., Lerner, J. V., & Lerner, R.M. (2014).

Profiles of problemaEc behaviors across adolescence: CovariaEons with indicators of PosiEve

Youth Development. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43(6) , 971-‐990.

• Bowers, E.P., Johnson, S., Buckingham, M., Gasca, S., Warren, D. J., Lerner, J. V., & Lerner,

R.M. (2014). Important non-‐parental adults and posiEve youth development across mid-‐ to late-‐adolescence: The moderaEng effect of parenEng profiles. Journal of Youth and

Adolescence, 43(6) , 897-‐918.

• Hilliard, L., Bowers, E. P., Greenman, K., Hershberg, R., Geldhof, G. J., Lerner, J. V., & Lerner,

R.M. (2014). Beyond the deficit model: Bullying and trajectories of character virtues in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43(6) , 991-‐1003.

• Napolitano, C. M., Bowers, E. P., Arbeit, M. R., Chase, P., Geldhof, G. J., Lerner, J. V., &

Lerner, R. M. (2014). The GPS to Success Growth Grids: Measurement properEes of a tool to promote intenEonal self-‐regulaEon in mentoring programs. Applied Developmental Science,

18(1) , 46-‐58.

THANK YOU!

QUESTIONS????

LERNERJ@BC.EDU

Let me know if you want to par+cipate in our research!