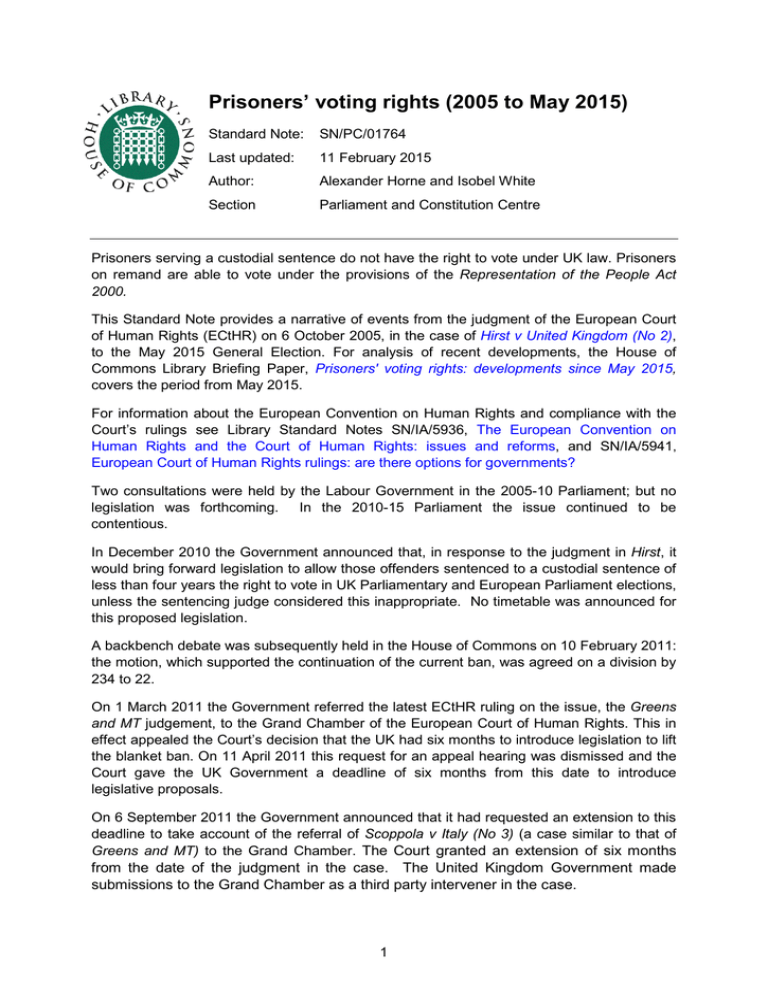

Prisoners’ voting rights (2005 to May 2015)

advertisement