:^Bi:::-: mlmmm 9080 01917 6624 3

advertisement

MIT LIBRARIES

3 9080 01917 6624

';:a!!KIJKJtf!?i-::

mlmmm

'

:^Bi:::-:

^^^;li§lfi0l!§0§illln::

mjiinmimiijm

:

^^

r -v;

Digitized by the Internet Archive

in

2011 with funding from

Boston Library Consortium

Member

Libraries

http://www.archive.org/details/creativedestructOOcaba

DEWEY^

Technology

Department of Economics

Working Paper Series

Massachusetts

Institute ot

AND DEVELOPMENT:

AND RESTRUCTURING

CREATIVE DESTRUCTION

INSTITUTIONS, CRISES,

Ricardo

J.

MIT Dept of Economics

Hammour, DELTA and CEPR

Caballero,

Mohamad L.

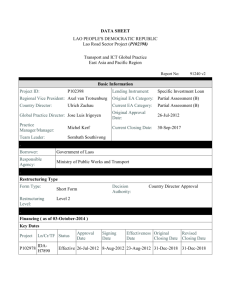

Working Paper 00-1

August 2000

Room

E52-251

50 Memorial Drive

Cambridge, MA 02142

This paper can be downloaded without charge from the

Social Science Research

Network Paper Collection at

http:/ /papers. ssrn.com/paper.taf?abstract_id=XXXXXX

MASSACHUSETTS iN:^! iuTt

OF TECHNOLOGY

I

2 5 2000

LIBRARIES

Technology

Department of Economics

Working Paper Series

Massachusetts

Institute of

AND DEVELOPMENT:

AND RESTRUCTURING

CREATIVE DESTRUCTION

INSTITUTIONS, CRISES,

Ricardo

J.

MIT Dept of Economics

Hammour, DELTA and CEPR

Caballero,

Mohamad

L.

Working Paper 00-1

August 2000

Room

E52-251

50 Memorial Drive

Cambridge, MA 02142

downloaded without charge from the

Science Research Network Paper Collection at

This paper can be

Social

http:/ /papers. ssrn.com/paper.taf?abstract_id=XXXXXX

CREATIVE DESTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT:

INSTITUTIONS, CRISES,

Ricardo

J.

AND RESTRUCTURING*

Caballero

MITandNBER

Mohamad L. Hammour

DELTA^ and CEPR

July 20, 2000

Abstract

There

increasing

is

empirical

evidence

experimentation and the adoption of

sunk,

is

a core

new

that

creative

mechanism of development. Obstacles

obstacles to the

progress

in

standards

destruction,

products and processes

of

living.

driven

when investment

by

is

be

underdeveloped and

to this process are likely to

Generically,

major impediment to a well-fimctioning creative destruction

and result in sluggish creation, technological "sclerosis," and spurious

reallocation. Those ills reflect the macroeconomic consequences of contracting failures in

the presence of sunk investments. Recurrent crises are another major obstacle to creative

politicized institutions are a

process,

destruction.

The common inference

increased restructuring

is

that increased liquidations during crises result in

unwarranted. Indications

the restructuring process

and

that

this

is

are, to the contrary, that crises freeze

associated with the tight financial-market

conditions that follow. This productivity cost of recessions adds to the traditional costs of

resource under-utilization.

Prepared for the Annual World Bank Conference on Development Economics, Washington, D.C., April

We thank Abhijit Banerjee for his discussion of our paper and two anonymous referees for

18-20, 2000.

their suggestions.

^

DELTA

is

a jomt research unit,

CNRS - ENS - EHESS.

Introduction

The world economy today

is

undergoing momentous reorganization

of the

in the face

development and large-scale adoption of information technologies. Alan Greenspan

describes the recent

clearly

US

more than most,

.

.

in the grip

is

of what

.

.

.

Joseph Schumpeter

- has begun

information technologies

.

.

.

called fcreative

by which emerging technologies push out the

coming together of the technologies

.

999

experience in the following words: 'The American economy,

destruction,' the continuous process

The remarkable

1

that

make up what we

to alter, fundamentally, the

business and create economic value". This

wave of

manner

restructuring

is

in

old.

label

...

IT -

which we do

only the latest

manifestation of creative destruction, by which the production structure weeds out

unproductive segments; upgrades

to the evolving regulatory

Ongoing

restructuring

is

its

technology, processes, and output mix; and adjusts

and global environment.

as relevant for the developing

leading edge of technology. In this paper,

we draw on

world as

it is

for

economies

at the

the significant advances over the

past decade in theoretical and empirical research on creative destruction to formulate a

number of propositions concerning

the role and workings of this

mechanism

in the

development process. Some of the ideas we put forward are firmly grounded in empirical

evidence;

others

theoretical

are

more than hypotheses consistent with

not

considerations

and

scattered

evidence,

but

a

combination of

which deserve

systematic

investigation in the future.

The

rest

of

this

paper

is

organized into three sections. In the

first

section,

we review

recent international evidence on gross job flows that supports the idea that creative

destruction

is

a core

mechanism of growth

around three basic

facts. First, the large,

destruction flows

exhibited by

all

in

market economies. Our discussion revolves

ongoing, and persistent gross job creation and

market economies studied provides evidence of

extensive ongoing restructuring activity. Second, this reallocation process shifts resources

over time fi-om low to high-productivity

sites,

and

is

found

to

account for a large share of

the growth in productivity. This highlights the central role of creative destruction in

productivity growth. Third, the very large majority of gross flows take place within

narrowly defined sectors of the economy. This implies that traditional analyses of

restructuring that emphasize shifts across production sectors

changes only capture a small component of

observe

a

for

calls

different

relative price

phenomenon. The bulk of what we

this

which

of analysis,

sort

and associated

emphasizes

theories

of

experimentation and technology adoption ^evinsohn 1999 and Melitz 1999 apply those

ideas to trade reform, Olley

Hammour

andPakes 1996

to industrial deregulation,

1999 to the effect of crises on restructuring

by those

role played

the idea of a 'big

silent flows

may

activity).

call for a shift in the

and Caballero and

Further exploration of the

development paradigm from

push" to a myriad of 'little nudges."

If creative destruction

is

mechanism of economic growth, obstacles

a core

are likely to be obstacles to development. This

is

to this process

many

of particular relevance to

developing economies today, which have opened up their markets and must

now

face the

challenge of not only catching up, but keeping up with world standards. The second

section argues that institutional impediments are likely to constitute major obstacles to a

well-functioning creative destruction process, and explores their consequences.

notion of restructuring

partly irreversible,

production

for

which

it

is

on the assumption

built

and specific with respect

combines with. Relationship

a proper institutional

growth

as the root obstacle to

impediment

to

skills is

technology or the other factors of

is critical. If

developing world,

we

it is

consider institutional failure

likely to constitute a

major

to creative destruction.

We explore the

consequences of constrained contracting

ability in the financial

markets on the restructuring process. Generically, such problems result

creation; technological sclerosis, in the

units; a disruption

of the

exit should take place;

result

and

specificity requires inter-temporal contracting,

framework

in the

that investment in capital

Any

strict

form of

inefficient survival

in

and labor

depressed

of low-productivity

productivity ranking based on which efficient entry and

and privately inefficient separations. Such

ills

can be as much a

of underdeveloped institutions as one of politicized institutions in response to the

distributional

effects

of restructuring.

On

the empirical

front,

we

explore available

LDCs

evidence on job flows in

on

the above questions.

LDCs, those flows may

and the many issues

Although there

evidence of significant job flows in some

is

reflect a highly unproductive restructuring process.

reach any conclusive evidence, a

than what has been attempted so

The

that arise in bringing the data to bear

much more

structural empirical

approach

contradicts the

commonly held view

that

line

likely to

of argument

observed sharp liquidations during crises result

However, jobs

in increased restructuring.

required

is

world are

second major obstacle to creative destruction. This

a

to

far.

third section argues that recurrent crises in the developing

constitute

However,

that are destroyed during a recession

mostly

feed into formal unemployment or under-employment in the informal sector, and not

directly

into

newly created

jobs.

We

argue that this issue can only be examined

d5mamically, and depends crucially on the behavior of creation and destruction during the

ensuing recovery.

that,

We extrapolate

on the contrary,

due to the

US

new production

from technological

units.

gross flows the proposition

and

crises freeze the restructuring process

tight financial conditions following a crisis,

the creation of

suffer

from empirical work on

that this

which reduce the

Given the presumption

that

phenomenon

is

ability to finance

developing economies

sclerosis, the result is a productivity-cost

of crises that adds to

the traditional costs associated with under-utilized resources.

Creative Destruction and Economic

In this section,

we review

recent empirical evidence that supports the notion that the

process of creative destruction

market economies - an idea

it

"the essential fact

is

that

a major

phenomenon

at the

core of economic growth in

goes back to Joseph Schumpeter 1942,

who

considered

about capitalism" (p. 83).

Underlying any notion of restructuring

output mix,

Growth

modes of organization

are

is

the assumption that choices of technology,

embodied

in capital

and

skills.

This irreversibility

of investment entails that adjusting the production structure requires that existing

investments be scrapped and replaced by

perfectly

malleable

and

skills

incessant

opportunities

it

upgrade

to

ones.

generic,

fully

instantaneous. At a conceptual level,

new

is

the

the

If,

on

were

the contrary, capital

adjustment

would be

and

costless

embodiment of technology combined with

production

structure

place

that

restructuring at the core of the growth process, irrespective of whether the

ongoing

economy

is

a

technological leader or laggard.

Restructuring

it is

is

closely related iofactor reallocation. If investments need to be scrapped,

because they are working with factors of production that must be freed up to combine

with

new forms of

factors in

investment. In other words, restnicturing generates a reallocation of

which technology

is

not embodied. This link has been exploited empirically to

develop measures of reallocation that can be used as an index of restructuring. The most

successfiil

measures developed so

been attempts

The

literature

far are

based on labor reallocation, although there have

to look at other factors (see, e.g.,

Ramey and

Shapiro 1998).

^

on gross job flows has constructed measures of aggregate gross job

creation and destruction based on

microeconomic data

at the level

of business units -

i.e.,

plants or firms (see Davis and Haltiwanger 1998 for an excellent survey). Gross job

creation over a given period

units

that

expand or

employment

losses

start

summed

is

defined as employment gains

summed

over

all

business

up during the period; gross destruction corresponds to

over

all

units that contract or shut

down. Although job flows

between the two

constitute a useful indicator of restructuring, the link

is

loose.

It is

quite

possible that plant equipment and organization be entirely upgraded in a given location

without a change in the number of jobs; conversely,

from one location

Many

to another (e.g., for tax reasons) to

studies are

now

possible that jobs

may

perform exactly the same

migrate

activity.

available that construct measures of job flows for different

countries. Three features of the data

of creative destruction

it is

in the

have emerged

growth process:

that

allow us to characterize the role

1

Gross job creation and destruction flows are large, ongoing, and persistent.

2.

Most job flows

take place within rather than between narrowly defined sectors of the

economy.

3.

Job reallocation from less-productive to more-productive business units plays a major

role in industry-level productivity growth.

Starting with the first feature, table

1

summarizes the average annual job flows measured

for different economies. Job flows are generally large, both in high-income countries and

for the

few observations we have of LDCs (Colombia, Chile and Morocco) and

economies (Estonia).

It is

very

common

that

an average of

at least

one

transition

in ten jobs turns

over in a year. Creation and destruction flows are simultaneous and ongoing. In

US

manufacturing over the period 1973-88, for example, the lowest rate of job destruction in

any year was

6.1

percent in the 1973 expansion; and the lowest rate of creation was 6.2

percent in the 1975 recession.

Moreover, the bulk of those flows are not a case of

temporary layoffs - which would not correspond

data for a

number of

Table 2 presents

to true restructuring.

countries on the high persistence rates of job creation and

destruction over a one-year and a two-year period

(i.e.,

the percentage of

newly created

jobs that remain filled over the period; or of newly destroyed jobs that do not reappear

over the period). Overall, job flow data seem to indicate extensive ongoing restructuring

activity.

The second

feature of the data

is

that reallocation across traditionally defined sectors

accounts for only a small component of job flows.

To measure

destruction that take place simultaneously above the

net

amount of creation and

amount required

employment changes, define excess Job reallocation

destruction minus the absolute value of net

the

as the

to

sum of job

employment change. Table

accommodate

creation and

3 presents data for

various economies on the fraction of excess reallocation accounted for by employment

^

An

and asks how much

See Hulten 1992 and

alternative empirical approach to creative destruction focuses on physical capital,

of output growth

IS

associated with capital-embodied technological progress.

Greenwood, Herkowitz and Krusell 1997.

See Davis, Haltiwanger and Schuh 1996, table

2.1, p. 19.

shifts

between narrowly defined

typically well

below

sectors. This fraction

never exceeds one-fifth, and

is

this level.

There seems to be two major factors behind within-sector reallocation: adjustment and

Needless

experimentation.

to

job

several

say,

characteristics

are

that

important

determinants of employment adjustment are not captured by output-based sectoral

classifications.

The job may be associated with

Hammour

and

(see, e.g., Caballero

In addition,

disruption.

it

capital or skills

may have

1996b), or

of an outdated vintage

suffered a highly idiosyncratic

appears that a large component of job flows

due

is

to

experimentation in the face of uncertain market prospects, technologies, cost structures,

or managerial ability (see,

US

e.g.,

Jovanovic 1982). This idea

is

supported by evidence from

manufacturing and elsewhere that younger plants exhibit higher excess reallocation

rates,

even

controlling

after

Haltiwanger 1998,

for

and figure

p. 18

a

variety

of plant characteristics (see Davis and

4.2).

Traditional analyses of restructuring in the trade and development literature emphasize

one dimension of the creative destruction process - namely major

sectors of the

decisions

whose

economy.

Much

less noticed is the multitude

driven by highly decentralized idiosyncratic

role is potentially equally important.

may come

under a new

light

once

we

Many

In

a

similar

vein,

telecommunications

reallocation toward

gains.

in

this

between main

of creation and destruction

factors

and experimentation,

conventional questions in development

consider the role played by those underlying flows.

For example, Levinsohn 1999 andMelitz 1999 argue

reform arises through

shifts

that a significant benefit

of trade

channel fi-om factor reallocation toward more productive firms.

Olley

industry

and Pakes

increased

more productive

Our coming discussion of the

1996

find

that

productivity

plants, rather than

deregulafion

predominantly

U.S.

the

through

factor

through intra-plant productivity

on restructuring

effect of crises

in

activity

and

its

costs

terms of productivity constitutes another example.

The function of

large within-sector job flows

brings us to the third feature of the data. There

and

is

their relation to productivity gains

evidence that factor reallocation

is

a

core

mechanism

growth of productivity. Foster, Haltiwanger and Krian 1998

in the

conduct a careful

and survey of

study

this

question.

Examining

U.S.

four-digit

manufacturing industries over the ten years 1977-1987, they decompose industry-level

multifactor productivity gains over the period into awithin-plant term and a reallocation

term.

by

The within-plant term

reflects productivity gains within continuing plants

their initial output shares; the reallocation

weighted

term reflects productivity gains associated

with reallocation between continuing plants, entry and

exit.

They

find that reallocation

accounts on average for 52 percent of ten-year productivity gains. Entry and exit account

for half of this contribution: plants that exit during the period

have lower productivity

than continuing plants; plants that enter only catch up gradually with continuing plants,

through learning and selection effects.

Other studies of

US

Baily, Hulten and

conclusion

that

Campbell 1992; Bartelsman and Dhrymes 1994) concur with the

accounts

reallocation

productivity growth.

productive in

manufacturing based on somewhat different methodologies (see

It

LDCs

would be of

as

methodological issues.

it

is

for

a

major component of within-industry

great interest to

know whether

US, but relevant

in the

Aw, Chen and Roberts

studies are

restructuring

few and give

is

as

rise to

1997, focus on Taiwar; Liu and Tybout

1996 on Colombia. Both define the within-plant term of their productivity decomposition

based on a

average share over the period rather than

plant's

discussed by Foster

et

reallocation

continuing

across

al.

1998,

this

tends

plants.

to

its

initial

share. ^

As

under-estimate the contribution of

Moreover,

both

conduct

studies

their

decomposition over a horizon shorter than ten years: five years for Taiwan, and only one

year for Colombia. This reduces the contribution of entry, which takes place dynamically

through the above-mentioned learning and selection effects.

the cyclicality of productivity,

within plants.

The

which one expects

It is

also

more

to affect productivity

sensitive to

growth mostly

resulting contribution of reallocation to average producfivity gains

is

34 percent for Taiwan, and near zero for Colombia.^ Given the methodological

In fact

Aw, Chen and Roberts 1997

use firm rather than plant-level data, and define a within-firm term.

Since sector weights are not provided by

weight to the

TFP growth

Aw

rates in their table

1

2.

et al.

1997, the calculated average contribution gives equal

differences,

LDC

it

countries

is

difficult to

is

less

know whether

this

imphes

that factor reallocation in those

productive than in the US.

The evidence of extensive, ongoing job flows

that are pervasive throughout the

and constitute a major mechanism of productivity growth points

creative destruction in the growth process.

productive in

LDCs

as

it is

in

Whether ongoing

an advanced economy

like the

to the centrality

restructuring

US

is

economy

is,

of

in fact, as

a major concern, but

does not diminish the potential importance of this process for growth.

A

corollary

is

it

that

obstacles to creative destruction are likely to be obstacles to development, and should be

of central concern to development theory and policy. Such potential obstacles are the

focus of the rest of this paper.

Institutions

We

and Restructuring

have seen

irreversible.

that

the notion of restructuring presumes that investment

When two

factors

is

partly

of production enter into a production relationship, they

develop a degree of specificity with respect to each other and to the choice of technology,

in the sense that their

value within this arrangement

is

greater than their value outside. In

the presence of specificity, the institutional environment

becomes

critical.

The reason

is,

very generally, that irreversibility in the decision to enter a production relationship with

another factor creates ex-post quasi-rents that need to be protected through ex-ante

contracting (Klein, Crawford and Alchian 1978). If contracting ability

institutional

the

value

by

of what

employment and output

process.

limited,

it is

the

environment that determines the rules by which those quasi-rents are

divided. Poor institutions,

getting

is

definition, prevent

it

put

in.

one of the parties

to a transaction

from

This disrupts the broad range of financing,

sale transactions that underlie a healthy creative destruction

We

view

institutional failure as the root obstacle to

world/ This leads us

major disruption

on an

to the

in the

developing

presumption that poor institutions are likely to constitute a

To

to creative destruction.

new dimension

entirely

economic growth

the extent that investment irreversibility takes

presence of contracting difficulties,

in the

it

becomes of

crucial import for the analysis of development.

we propose

In this section,

restructuring

process

a simple

model of the

and examine related

common

systematic fashion and which

is

regulations, highly politicized

Our treatment of

evidence.

not to

is

element likely

shared by

financial markets that lack transparency

empirical

Our purpose

institutions is deliberately very generic.

arrangements, but to identify a

distortions that are likely to affect the

comment about

specific

to affect creative destruction in a

many examples of

-

institutional failure

and investor protection, overly protective labor

and uncertain competitive regulations,

etc.

Theoretical Considerations

A

basic model.

We

which focuses on

develop a basic model, based on Caballero and

we

implications for aggregate restructuring. For this purpose

entrepreneurs affects financing transactions;

employment

transactions.

All

three

Entrepreneurs and labor have linear

which we use

The

its

1998a,

and employment relationships and

specificity in the financing

production: capital, entrepreneurs, and labor.

Hammour

its

introduce three factors of

specificity of capital with respect to

specificity with respect to labor affects

factors

utility in the

exist

in

infinitesimally

small

units.

economy's unique consumption good,

as numeraire.

Contracting obstacles affect the possibility of economic cooperation. In order to capture

their implications at a general level,

we

define for each factor two possible

production; Autarky and Joint Production (see figure

factors

^

combine

in fixed proportions to

1).

form production

modes of

In Joint Production, the three

units.

Each such

unit

is

made up

See Lin and Nugent 1995 for a broad review.

10

of

(i)

a unit of capital;

(ii)

an entrepreneur

/;

and

(Hi) a

worker. Each entrepreneur

7,

of the consumption good the unit can produce. Each entrepreneur also

w^ith a level

of net worth

a,

>

that

can finance part of the

remaining financing requirement, 6, =

assume

to

that

workers

start

-

1

a,

is

the worker.

It

unit's capital

has no ex-post use outside

The Autarky mode of production

requirement. The

is

rise

fully specific to the entrepreneur

and

relationship with them.

its

free

is

We

provided by external financiers.

from investment

specificity. If they

participate in a Joint Production unit, factors can operate in the following

do not

Autarky modes:

Capital can be invested in the international financial markets at a fixed world interest

rate

/

>

for Autarky),

("/i" stands

(ii)

If

an entrepreneur does not enter Joint

Production, he simply also invests his net worth at the world interest

for

starts

with zero net worth. Cooperation in Joint Production gives

investment specificity: once committed, capital

(i)

has an

measured by the

innate level of skill that determines the production unit's productivity,

amount

/

Labor corresponds

informal-sector labor

U

(1)

where

to

employment

demand

= UiW^X

in the "informal" sector at a

rate. (Hi)

wage

w''

Autarky

given by the

function:

U'<0,

U stands for informal-sector employment.

In order to analyze restructuring,

we assume

the

economy

starts

with pre-existing

production units as well as a supply of uncommitted factors of production. Events take

place in three consecutive phases: destruction, creation, and production. In the destruction

phase, the factors in

all

pre-existing units decide whether to continue to produce jointly,

or to separate and join the

factors either

uncommitted

factors. In the creation phase,

form new Joint Production units or remain

in

uncommitted

Aurarchy. In the final phase,

production takes place and factor rewards are distributed and consumed. If the factors in

a Joint Production unit separate after the creation phase, their only option

is

to

move back

to Autarky.

11

Introducing pre-existing units allows us to analyze destruction decisions.

their productivity distribution

is

over the interval^" e

[0,

y'"'^]

has negligible mass. The supply of uncommitted factors

capital is unlimited,

y'""''']

is

(ii)

is

We

assume

and, for simplicity, that

as follows/i^

The supply of

The supply of entrepreneurs with any given productivity^ 6

also unlimited, but not all of

them have

We

positive net worth.

it

assume

[0,

that

entrepreneurs with positive net worth are distributed according to a uniform density 0>

and

for each productivity level,

production unit

(a,

Joint Production

is

>

-

Efficient equilibrium.

which would

(Hi)

have sufficient funds

The aggregate mass of labor

is

to fully finance a

one, so that

employment

U(\/).

We

first

arise if agents

derive the economy's efficient-equilibrium conditions,

had perfect contracting

ability.

We

restrict ourselves to

<L

parameter configurations that result in an interior equilibrium (0

<

On

1).

the

creation side, given that the supply of entrepreneurs with the highest productivity^"''"

unlimited and that the Autarky return on capital is/, labor's Autarky

wage must

is

satisfy

v/* =y'"'"-/

(3)

(a

in

given by

L=\

(2)

1).

that they all

"*" denotes efficient equilibrium values).

infinite Joint

of Joint Production

value would induce

(2)-(3) determines the efficient equilibrium creation

units, as illustrated in figure 2.

Note

that the Joint

Production rewards

and labor are equal to their Autarky rewards, and that the reward for

entrepreneurs

On

this

Production labor demand; and any wage below would induce zero demand.

The labor demand and supply system

for capital

Any wage below

is

zero because of their unlimited supply.

the destruction side, scrapping the capital invested in a pre-existing unit frees up a

unit of labor. Efficient exit will therefore affect

all

units with productivity levels

12

/ < v/*.

(4)

Incomplete-contracts equilibrium. Because of investment specificity, implementing the

efficient equilibrium requires a contract that guarantees capital in Joint Production

ante opportunity cost

inalienability of

removes the

/. The contracting incompleteness we introduce

human

capital,

worker

right of the entrepreneur or the

transaction

due

between labor and

to

Moore

capital,

ex-

to the

which renders unenforceable any contracting clause

Production relationship ex post (see Hart and

employment

is

its

that

walk away from the Joint

1994). This affects both the

and the financing transaction between

the entrepreneur and external financiers.

Starting with the

employment

relationship,

we assume

that the

worker deals with the

o

entrepreneur and his financier as a single entity. If production unit

its

associated specific quasi-rent

s,

is

i

has productivity yt,

the difference between the unit's output and

its

factors 'ex-post opportunity costs:

St=y,-W',

(5)

considering that the worker

the

Nash bargaining

moves

to

Autarky

if

he leaves the production

solution for sharing the unit's output,

ex-post opportunity cost plus a share of the surplus

Wi

(6)

where

w, and

;r,

problem adds a

Turning

full

= \/ +

I3si

and

Ki

=

si.

If p

we assume

unit.

Following

each party gets

e (0,1) denotes

its

labor's share:

{l-p)Si,

denote the rewards of labor and capital, respectively. The contracting

rent

component pSi

to

wages.

to the financing relationship, the associated specific quasi-rents

profit Ki because the

correspond to the

ex-post outside options of the entrepreneur and external

13

financiers are worthless. Again, because of the inahenability of

human

capital,

contract can prevent the entrepreneur from threatening to leave the relationship.

contract can be renegotiated according to the

ae

entrepreneur a share

firm's outside liability

(0,1)

of

Ttt

Nash bargaining

solution,

which gives the

and gives the external financier a share

(1-a).

The

can therefore never exceed

This financial constraint places a lower bound on the net worth

entrepreneur needs to

start a project,

which can be written

a,

=

1

-

6,

the

as

a,>\-{\-a)(\-p)(y,-w'y/.

(8)

based on

-

Any

/bt<{\-a)7ti.

(7)

yi

no

(5)-(6).

We assume a is

large

enough

that (8) requires positive net

y""^- This implies that only entrepreneurs with positive net

Production, in which case

we have assumed

that they

worth when

worth can enter Joint

have enough funds to fully finance

a production unit.

We now solve

for the incomplete-contracts equilibrium conditions. Starting with creation,

an entrepreneur

who

is

able to finance a production unit will find

profitable to

do so

if

;r,>/,

(9)

which, given (5) and

(6), is

yi>W +

(10)

equivalent to

[\+fil{\-P)y\

Because of the rent component

rate higher than r^

entrepreneurs

One

it

.

The

in

wages, capital behaves as

Joint Production

whose productivity

demand

satisfies (10)

if

for labor

it

is

faced a world interest

given by the mass of

and can finance a production

unit:

reason could be that the entrepreneur can disguise proper funds as being external, and vice versa.

14

L = (p[y'""'-W'-[\+m-l3)Vl

(11)

Together with equation (2) for the supply of labor,

As

contracts equilibrium level ofL.

incomplete contracts

falls

below

its

demand

illustrated in figure 2, labor

efficient-economy counterpart

because of labor-market rents (which

financial constraint

determines the incomplete-

this

shifts the

curve

down

(which rotates the curve down around

the incomplete-contracts equilibrium, Joint Production

(3).

vertically)

its

(11) under

This occurs both

and because of the

vertical-axis intercept). In

employment and Autarky wages

are lower than their efficient-equilibrium counterparts:

L<L*

(12)

Turning

find

>/<>/*.

and

to destruction, note that a

employment

in Joint

worker who leaves a pre-existing production unit

Production with probability!,

which case we denote

in

expected wage by E[w]; and will remain in Autarky with probability

case his

wage

will hew^.

The

/<Z£[w]

(13)

Characterization

+

(l

problems.

We

first

-L), in which

-!)>/.

of equilibrium.

macroeconomic

his

exit condition is therefore

We now

characterize

consequences of incomplete contracting. The imbalances

inefficient

(1

will

solution

to

the

we

unresolved

the

general-equilibrium

describe constitute a highly

microeconomic

contracting

discuss features of equilibrium that are highly suggestive of the

experience of developing countries, but pertain only indirectly to restructuring;

we

then

turn to direct implications for the restructuring process.

In order to avoid issues related to the possibility that the entrepreneur

production

unit,

we assume

may want

to restart in a

new

entrepreneurs in pre-existing units have zero net worth.

15

1.

Reduced cooperation. At

microeconomic

the purely

limited contracting ability hampers cooperation.

may

Joint Production projects

We

level,

it

well

is

known

that

have seen that positive-value

not be undertaken because labor (eqn. 6) or the

entrepreneur (eqn. 7) can capture rents beyond their ex-ante opportunity costs.

2.

we have

Under-employment. As

Production

is

seen in the discussion of equation (12), Joint

characterized by under-employment

consequence of obstacles

^ <L

to cooperation in the financial

),

which

is

an equilibrium

and labor markets. In

partial

equilibrium, rent appropriation reduces the Joint Production return on capital. In order

to restore this return to the level f^ required

units are created, informal-sector

component \/ of wages

depends on the supply

assume here

to

be

employment balloons, and

falls (eqn. 6).

elasticity

U

{U >

).

The reason

this

in Joint

happens

We

problems are

because there

low

the opportunity-cost

that suffers

from

which we

specificity,

infinite.

contracting in Autarky.

to

Joint Production

Generally, the extent of under-employment

of the factor

The counterpart of under-employment

sector

by world markets, fewer

less severe

Production

that

is

less

capital intensity or constant returns),

an overcrowded informal

we have assumed no need

view the informal sector

is

is

as

for

one where transactional

need for cooperation with

capital (due

because employment regulations can be

evaded, etc'

3.

Market segmentation. In the incomplete-contracts equilibrium, both the labor and

financial markets are segmented. There are workers

who would

doing

so.

strictly prefer to

strictly

component of

'°

Banerjee and

Joint Production

above the informal-sector wage.'

Newman

where contracting

Autarky

into Joint Production, but are constrained

not entail high wages, but quite the contrary.

sector

in

Put another way, those two factors earn rents in Joint Production.

to see that the rent

them

move

and entrepreneurs

'

wages

It is

in (6) is positive,

However, the presence of

One can show

and

from

easy

sets

rents does

that Joint Production

1998 apply a similar interpretation to thetraditional sector, which they see as a

easier because information asymmetries are less severe.

is

16

wages

for

are lower under incomplete contracts than in the efficient

any production unit

replace

Ttt

= yt

-

w, into (9) to get

rent

component of wages

arises through depressed

wages

in the informal sector,

not because of high wages in Joint Production. Similarly, from (10),

it

is

clear than an

entrepreneur with intra-marginal productivity^, earns positive rents equal to yt

[1

+

this

Wi<y,-/<y'"'"-/ = W'\

(14)

The

i,

economy. To see

p/{\

arise in

-

p)]r^ associated with the scarcity of internal fiinds.

w

-

-

Those rents would not

an efficient equilibrium.

We now

turn to the characteristics of equilibrium that pertain directly to restructuring.

The

three properties characterize the

first

of Joint Production

units; the last

from

as the net gain that results

4.

Depressed

two characterize

Sclerosis.

creation. Since creation in this

The

the quality of restructuring, understood

it.

the equilibrium rate of creation

5.

amount of equilibrium creation and destruction

is

economy

from

Joint Production structure suffers

the efficient

< W^ was shown

and incomplete-contracts

in (12) for

equal toL

<L

,

it

follows that

depressed compared to the efficient economy.

production units survive that would be scrapped

compare

is

in

sclerosis, in the

some

an efficient economy. To see

exit conditions, (4)

Autarky and w, < v/*

sense that

and

(13).

this,

Sincew

in (14) for Joint Production,

it

is

clear that cost pressures to scrap are lower in the incomplete-contracts than in the

efficient equilibrium.

Sclerosis

is

thus a result of the under-utilization and

low

productivity of labor. Sluggish creation and sclerosis can impose a heavy drag on

aggregate productivity.

6.

Unbalanced

rate

'

'

restructuring. Destruction

of creation. To see

Simply note

that (9) impliesTz;

this,

>

is

excessively high compared to the depressed

note that the private opportunity cost used in (13) for exit

0.

17

decisions

is

higher than the social shadow

wage v/ of

labor. This is

due

to the

possibihty of capturing a rent component in wages, which distort upwards the private

opportunity cost of labor.

sclerosis

may

It

appear paradoxical that the economy exhibits both

and excessive destruction. In

and the

efficient equilibrium

latter is a

fact, the

former

is

a comparison with the

comparison between private and social values

within the incomplete-contracts equilibrium. The unbalanced nature of gross flows

is

closely related to the presence of rents and market segmentation. In Caballero and

Hammour

1996a,

we

argue that

sheds light on the nature of employment crises in

it

developing countries.

7.

Scrambling. In the efficient economy, only the most productive entrepreneurs withy

=

y""^ are involved in Joint Production.

would have been brought

side,

Had

number been

their

insufficient, others

in according to a strict productivity ranking.

an efficient process should result

implemented. This ranking

is

scrambled

On

the creation

in the highest-productivity projects

being

in the incomplete-contracts equilibrium, as

another characteristic of the entrepreneur - net worth

- comes

into play. This tends to

reduce the quality of the chum, in the sense that the same volume of scrapping and

re-

investment will result in a smaller productivity gain.

8.

Privately inefficient separations.

in our model, but

A

which can also

difficulties, is the possibility

dimension

assume

that

that a production unit

must be financed

and subject

actually not incorporated

oprivately inefficientseparations. This can

from

make

come about

creation privately inefficient, in the sense

starting positively valued projects.

For example,

goes through a period of temporarily negative cash flow

if the

unit is to

investment would help preserve the

specific

we have

constitute an important consequence of contracting

through factors similar to those that

that agents are constrained

that

remain

unit's

to a financial constraint.

in

operation.

specific capital,

When

and

Such continuation

is

therefore itself

the financial constraint

is

binding,

destruction can be privately inefficient and result in losses for the owners of both

labor and capital.'^ This gives rise to another factor that reduces the quality of

'^

See, e.g., Caballero and

Hammour

1999 for

details.

18

restructuring, as

generates spurious churn with

it

we admit

Moreover, once

gains.

little

payoff in terms of productivity

of private inefficiency on the

the possibility

destruction margin, then factors other than productivity

and also scramble the productivity ranking

Although

economy.

Political

inalienability

specificity

specific rents. Legal restrictions

make

it

founded

on

the

can be due to a variety of factors. In

in itself,

framework

institutional

was

incompleteness

contracting

and regulatory framework can,

and provide the

affect those decisions

in exit decisions.

of human capital in our model,

particular, the legal

may

that

be a source of factor

determines the division of

on employee dismissals, for example, would effectively

capital partly specific to labor in the Joint Production relationship analyzed above.

Moving beyond an exogenous view of institutions,

in this section concerns

some of

the final theoretical issue

we

touch on

the underlying causes for the institutional obstacles to

efficient restructuring.

Institutions play

two

distinct functions: efficiency

naive to think that markets

institutional

in

-

i.e.,

is that

On

one hand,

it is

can generally function properly without an adequate

framework. In their efficiency

determines institutions

and redistribution.

each factor ought

absent any externalities,

its

we have

role,

seen that the basic principle that

to get out the social value

ex-ante terms of trade.

On

of what

it

the other hand,

put

it

is

equally naive to think that such institutions, being partly determined in the political arena,

will not also be used as an instrument in the politics of redistribution.

framework

the

is

result

A

of a combination of under-development

poor institutional

in

the

contracting and regulations and of overly powerful political interest groups

tilted the institutional

By

displacing

incumbent

endogenous

who have

balance excessively in their favor.

technologies

interests,

realm of

and

skills,

and can therefore

institutional

barriers.

restructuring can, in fact, prop

creative

itself

Mere

destruction

give

rise

uncertainty

to

threatens

political

concerning

a

variety

of

opposition and

the

impact

of

up opposition (Fernandez and Rodrick 1991). Mokyr 1992

19

discusses

many

most popular of which

1972).'^

examples of resistance

historical

is

technology adoption, perhaps the

to

the nineteenth century Luddite

movement

in Britain

fhomis

The response can range from mere neglect of the urgency of institutional reform

to active barriers affecting trade, competition, regulation, the size of the

sector, as well as the financial

and labor market dimensions

that

we

government

focused on in our

model.

As we have

seen, a

major

factors characterized

large-scale

by

pitfall

of such protection,

if

intended to protect labor or other

relatively inelastic supply, is that

under-employment and

internal segmentation

benefiting from protection and those

number of Latin American economies

who do

(e.g.,

not.

This

it

can backfire and

result in

between those who end up

pitfall is

worth highlighting as a

Chile and Argentina) go through the process

of revising their labor codes in the context of ever increasing globalization and expanding

outside options for capital (see Caballero and

Hammour

1998b).

A Look at Available Evidence

Theoretically,

we have argued

that

poor

institutions generally result in a stagnant

and

unproductive creative destruction process. If one considers institutional failure as the

fiindamental illness of the developing world, then one

low-quality

Although

chum

this is consistent

direct evidence

table

1

are prevalent

countries

we have

"

economy

Political

that sclerosis

and

a

phenomena.

with low productivity in

from job flows on

do hot seem

would presume

this issue.

to support the idea

of

At

LDCs, one would

first sight,

sclerosis.

the data that

like to find

more

were presented

in

Job flows in the few developing

data on are of similar, if not larger, magnitude as in high-income

considerations have not failed to arise in the current debate on the impact of the IT

revolution: "a major consequence of rapid

economic and technological change

needs to be addressed:

growing worker insecurity - the result, I suspect, of fear of potential job skill obsolescence. Despite the

tightest labor markets in a generation, more workers report in a prominent survey that they are fearful of

losing their jobs than similar surveys found in 1991 at the bottom of the last recession. ...

Not

.

.

.

20

countries (see Tybout 1998). However, there are several powerful reasons

evidence cannot be taken

1

Measurement

1

issues. First,

highlights

this

at face value:

it is

job flow measures, which

Table

why

important to keep in mind the lack of uniformity in

may undermine

their comparability

across countries.

two major differences: sample coverage (manufacturing, private

employees) and the basic employer unit (the plant or the firm). Other

sector, all

important differences are more difficult to trace, most notably the difficulties in

linking observations longitudinally in the face of ownership or other changes. For

example, Contini and Paceli 1995 report that attempts to correct Italian data for

spurious births and deaths reduce job flows by about one-fifthl"^

2.

Industrial structure

and employer

characteristics.

The magnitude of job flows

varies

systematically with industrial structure and employer characteristics. First, Davis and

Haltiwanger 1998 show that the industry pattern of job reallocation intensity

similar across countries.

for pooled

3.4).

A

US, Canadian and Dutch data yields an R-squared of 48 percent

expect to find that

turnover

LDC

employment

low levels of investment

rate.

One

quite

regression of reallocation on 2-digit industry fixed effects

Although we are not aware of a systematic investigation of this

relatively

is

is

issue,

(table

we would

heavily biased toward light industries with

specificity

and

that typically experience a fast

expects this type of restructuring with small

re-investment

requirements to yield commensurately low productivity gains. Moreover, rather than

a sign of their ability to restructure, this

industries

where restructuring

is

may even

be an indication that

LDCs

avoid

expensive.

Second, Davis and Haltiwanger (1998, figure 4.1) summarize international evidence

from seven countries for which job reallocation rates

size.

Compared

to

fall

high-income countries, the bias

developing countries toward small plants

is

significantly with

in

dramatic (see,

the

e.g.,

size

employer

distribution

Tybout 1998,

table

in

1).

unexpectedly, greater worker insecurities are creating political pressures to reduce the fierce global

competition that has emerged in the

wake of our 1990s technology boom." (Greenspan 1999)

21

by

This,

itself,

reallocation

is

much

predicts

larger job

productive this type of

requires close interpretation. If small plant size

light-industry bias with

be small. Moreover,

if

little

is

closely related to the

technological lock-in, the benefits of restructuring

small plant size

some of the observed turnover may

3.

How

flows.

is

may

associated with greater financial fragility,

actually be privately inefficient

and unproductive.

Restructuring requirements. Given the extent of catching up ahead of them, one

would

actually expect developing economies to have significantly higher investment

and restructuring requirements. In

by Taiwanese

firms

may

manufacturing industries.

be

turnover rates experienced

fact, the extraordinary

a

case

in

In

point.

Aw, Chen and Roberts 1997

their

study

of Taiwanese

report that firms that entered

over the previous five years account for between one-third and one-half of 1991

industry output (table

plants

They

report that the equivalent figures for manufacturing

18 to 21 percent in Colombia; 15 to 16 percent in Chile; and 14 to 19 percent

is

in the

1).

US

(fh.

p.

3,

7).

Large turnover rates

Taiwan

in

developing countries have the potential to attain

much

are an indication that

higher restructuring rates

absent major impediments.

Another useful natural experiment can be found

Haltiwanger and Vodopivec

1

in Eastern

1,

transition.

997 studied the case of Estonia, which was one of the

most radical reformers. Estonia implemented major reforms

table

European

in 1992.

As

reported in

average annual job creation and destruction rates in Estonia over the period

1992-94 were 9.7 and 12.9 percent, respectively. Those figures are within the range

observed

in

momentous

enterprises

OECD

economies.

What

is

striking

that they coincided with a period

is

of

reforms. For example, between 1989 and 1995, the share of private

in

total

employment rose from

2

establishments with more than 100 employees

context, observed job flows in Estonia

to

fell

35 percent; and the share of

from 75

to

46 percent. In

were disappointingly low, which

is

this

not

surprising given the major institutional deficiencies faced by transition economies.

'"

See Davis and Haltiwanger 1998, table 3.2,

fn. b.

22

4.

So

Productivity.

far,

our discussion was limited to the volume of the chum. Our

theoretical discussion also pointed to other factors

and the scrambling

in the productivity

-

privately inefficient separations

ranking of entering and exiting units - that

reduce the quality of those flows. In principle, sclerosis

if the latter are relatively

consistent with large flows

is

unproductive. The quality of the

chum can be measured by

an accounting exercise of the type discussed in the previous section, which accounts

for the

aggregate productivity improvements associated with job flows. In our

discussion

of the

results

for

Colombia

and

Taiwan,

we

pointed

out

that

methodological issues do not allow direct comparison with results for the US. As

importantly,

it

should be pointed out that those studies do not account for the

scrapping and re-investment costs of restructuring.

by a higher-productivity

entrant,

one should account

investments in the former and reinvesting in the

in

When

latter.

a firm exits

for the

This

is

and

is

replaced

cost of scrapping

particularly important

comparisons between high and low-income economies, when employment

latter is

in the

biased toward light industries and other modes of production with low

reinvestment costs.

It

seems safe

to

conclude that cross-country comparisons based on raw job flow data are

unlikely to provide conclusive evidence on the efficiency of restmcturing.

structural empirical

From

this point

approach

is

needed

that addresses the type

of view, the corresponding empirical

Crises, Recovery,

Recurrent crises

in

A

more

of issues discussed above.

literature is still in its infancy.

and Productivity

developing economies have large welfare consequences.

these consequences are immediately apparent, while others manifest their

time and thus are often under-appreciated.

the dismptive effect that crises can have

A potentially major impact of the

on the restructuring process.

Some of

damage over

latter

type

In this section

is

we

explore this cormection. After clarifying a widespread misconception concerning the

23

relation

between liquidations and restructuring, we report evidence

conjecture that crises slow

down

the restructuring process. If this

is

that leads us to

and given our

so,

presumption of sclerosis in the production structure, crises are even more costly than

contemporaneous impact on unemployment and other aggregate indicators

At the

origin of the above-mentioned misconception

constitute the

most noted impact of contractions on

is

a stark

fact.

may

their

suggest.

Sharp liquidations

restructuring. Figure 3 illustrates this

point for the case of Chile's debt crisis in the early eighties. The job destruction rate

exceeded 22 percent of manufacturing employment

is

1981-82. Sharp employment

What

during recessions are also documented for other countries.'^

liquidations

fallacious

in

is

the unwarranted inference that the concentration of liquidations during crises

implies that crises accelerate the restructuring process. This view was highly influential

among pre-Keynesian

who saw

'liquidationists"

- such

liquidations in a positive light as the

1990). Although few economists today

Hayek, Pigou, Robbins, Schumpeter -

as

main function of recessions

would take such an extreme

(see

position,

De Long

many

see in

increased factor reallocation a silver lining of recessions. Observed liquidations are seen

as a prelude to

much-needed

restructuring.

Under

the presumption of technological

A

sclerosis due to poor institutions, increased restructuring can be beneficial.

liquidationist

arguments were

advanced,

for

example,

during

the

Asian

variety of

crisis

in

connections with the reorganization of Korean c/zae6o/5'.

Although there seems

to

be

some

truth

notion

the

to

that

recessions

facilitate

reorganization at the level of politics and institutions, the relation between increased

restructuring and increased liquidations

is

much

less

obvious insofar as

directly with adjustments in the productive structure.

recessions typically feed into formal

are concerned

fact is that lost jobs during

unemployment or under-employment

sector, not directly into increased creation

-

a

phenomenon we

section as a case of "unbalanced restructuring."

that a large fraction

US

in the informal

interpreted in the previous

The question

See Davis, Haltiwanger and Schuh 1996 for evidence from

been conducted, they have shown

The

we

is

whether, ultimately.

manufacturing.

Where

of destruction during contractions

is

analyses have

permanent (see

Davis and Hahiwanger 1992).

24

increased liquidations lead to increased restructuring. In order to assess this question, one

needs to examine the cumulative impact of a recessionary shock on creation and

destruction. In other

impact, but also

how

words one needs

to

examine not only the

of the

effect

the recovery materializes. Figure 4 illustrates this issue

three scenarios that are consistent with a given

spike in liquidations (bottom panel).

The

unemployment recession

crisis at

by showing

that starts with a

three scenarios correspond to cases

where the

recession results cumulatively in increased, unchanged, or decreased restructuring (panels

(a), (b)

and

(c),

We

examined

the

US

respectively).

question empirically in Caballero and

this

Hammour 999

1

using data from

manufacturing sector. Figure 5 presents the gross job creation and destruction

US

time series constructed by Davis and Haltiwanger 1992 for

manufacturing. Most

notable in those series are the sharp peaks in destruction at the onset of each recession,

while the

fall in

creation

much more muted. Although

is

and destruction may not be as strong

shocks of a different nature,

this

in other sectors, or

this

asymmetry between creation

when

the

economy

is

subject to

evidence confirmed the long-held view that liquidations

are highly concentrated in recessions.

Is the

evidence

in figure 5

supportive of incrcasedrestructuring following recessions? In

order to examine the cumulative impact of a recessionary shock on creation and

destruction,

we

ran a simple one-factor regression and calculated the impulse-response

functions reported in figure

6."

The bottom panel

reports the cumulative impact of a

recessionary shock on creation and destruction. Surprisingly, recessions

the

amount of restructuring

in the

economy. This

result

seem toreduce

of "chill" following recessions

is

significant and robust in several dimensions, including the introduction of a second,

reallocation shock. Given the limitations of the data, our conclusion can only be tentative.

The regression underlying

(//,),

employment^,), the flow of gross job creation

from their mean. The data are quarterly for the

employment fluctuations are driven by a single aggregate shock.

figure 6 uses manufacturing

and the flow of gross destruction (D,)

period 1972T- 1993:4.

Given the

identity

We

assume

AN, = H,

-

that

in deviation

D,, a linear time-series

model

for the response of job flows to aggregate

shocks can generally be written either in terms of creation://, =

(!l'{L)N,

=

operator/. Figure 6 portrays the estimated

0'{L)N,

+

£^„

where

6l'{L)

and 0'{L) are polynomials

in the lag

+

£*,;

or in terms of destruction: D,

impulse-response functions for a 2-standard-deviationrecessionary shock.

25

But, if there

is

any evidence,

it

does not support prevailing views that recessions are the

occasion for increased restructuring.

Why

would recessions freeze

in Caballero

and

Hammour

are financial constraints

open

failure

-

Based on the model we develop

the restructuring process?

1999, our interpretation

that the

is

again, a case of institutional failure.

main underlying

factors

While liquidations and the

of bankrupt firms make the news, recessions also squeeze the liquidity and

financial resources

needed to create new, more advanced production

takes place, the competitive pressure from

productivity incumbents can survive

new production

more

easily.

The

As

units.

units slows

the latter

down and low-

scarcity of financial resources

during the recovery limits the socially useful transfer of resources from low to high

productivity units.

'^

While we do not have access

developing economy,

it

plausible that the

is

1

in

developing economies.

to the data required to

R

If there

economies are more marked, and

is

likely to be

same phenomenon

any difference, the

their depressing effect

even stronger. Figure

Mexico and Argentina

is

reproduce the above study for a

7, for

example,

liquidity contractions in those

on creation during the recovery

illustrates the severe credit

that followed the "tequila" crisis

each panel depict the path of private deposits and loans.

'^

also characterizes crises

crunch in

of the mid-90s. The two lines in

It is

clear

from

this

episode that

Fluctuations in the pace of restructuring can be approached from a very different angle, by

moving from

job reallocation to the restructuring of corporate assets. Looking at merger and acquisition ("M&A")

activity over time, and at its institutional underpinnings, we reach a conclusion that also amounts to a

rejection of the liquidationist perspective (see Caballero

this context

would consider

fire

restructuring of corporate assets.

and

Hammour 2000).

Essentially Jiquidationism in

sales during sharp liquidity contractions as the occasion for intense

The evidence

points,

on the contrary,

to briskly

expansionary periods

characterized by high stock-market valuations and abundant liquidity as the occasion for intense

Again, financial factors and their institutional underpinnings seem to be

restructunng phenomenon.

activity.

at

M&A

the core of this

would probably be unwise to look for direct evidence of depressed reallocation along the lines we did

The reason is that crises in developing economies often involve large changes in relative prices

(e.g., the large real devaluation during Mexico's tequila crisis), which naturally induce reallocation. The

right metric is then one that controls for this purely neoclassical mechanism

'^

It

for the U.S.

26

loans to the private sector not only recovered very gradually after the crisis, but also did

so slower than deposits.

In sum, even though direct evidence

major obstacle

is

lacking,

it is

likely that crises constitute another

to a well-functioning restructuring process,

closely associated with problems in financial markets.

social cost of

economic

crises that

is

The

and

that this disruption is

result is a productivity-based

incurred in addition to the traditional cost based on

under-employment and the under-utilization of other resources. The cost of

terms of restructuring

is

crises in

twofold. First, crises are likely to result in a significant amount

of privately inefficient liquidations, leading to large costs of job loss and liquidations of

organizational capital. Second, crises are likely to result in a freezing of the restructuring

process and years of productivity stagnation.

Conclusion

A

core

mechanism of economic growth

modem

in

market economies

is

the massive

ongoing restructuring and factor reallocation by which new technologies replace the

old.

major aspects

of

This

process

of Schumpeterian

creative

destruction

permeates

macroeconomic performance - not only long-nm growth, but

also

economic fluctuations

and the fimctioning of factor markets. Unfortunately, the process of creative destruction

is

also fi-agile, as

it

is

exposed

to political short-sightedness,

inadequate contractual

environments, and financial underdevelopment.

In this paper

supporting

we have reviewed

this

creative-destruction

problems. While the evidence

we

a great leap to conjecture that

economies. In

both theoretical arguments and empirical evidence

fact,

it

of macroeconomic

view

presented

is

performance

mostly from developed economies,

also applies in

many of

the latter typically suffer from

its

and

it is

its

not

dimensions to developing

more severe

deficiencies in their

contractual environment, and their financial systems often suffer severe

damage during

The slow recovery of loans

back

for

its

in Argentina was caused by government's crowding out as it borrowed to pay

"monetary" intervention and, most importantly to our argument, by the sharp consolidation

process experienced by the banking sector following the

crisis.

27

crises.

These are the two most significant ingredients behind sclerosis and behind

inefficient restructuring following contractions.

There

is

no doubt

that there is a significant

need for new and more structural empirical

evidence on the workings of the creative-destruction process and

economies.

this

We

hope

that this

its

perils in

developing

paper has pointed to some of the most promising issues in

worthy agenda.

28

References

Aw, Bee-Yan, Xiaomin Chen and Mark Roberts

'Firm-Level Evidence on

(1997):

Productivity Differentials, Turnover, and Exports in Taiwanese Manufacturing,"

NBER Working Paper no.

6235.

Baily, Martin, Charles Hulten and

David Campbell (1992): 'Productivity Dynamics

Manufacturing Plants," Brookings Papers on Economic

Activity,

in

Microeconomics,

187-267.

Banerjee, Abhijit V., and

Andrew Newman

(1998): 'Information, the Dual

Economy, and

Development,''' Review ofEconomic Studies, 65, 631-653.

BarteJsman, Eric

and Phoebus

J.,

J.

Dhrymes