Organized Anarchy: Senior Honors Thesis Sociology

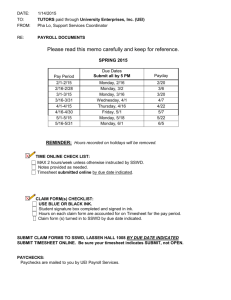

advertisement