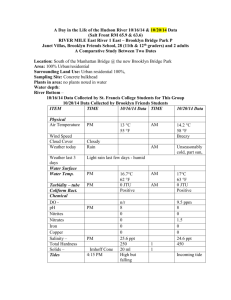

Creating the City:

advertisement