HUMAN RIGHTS Additional Guidance, Monitoring, and Training Could

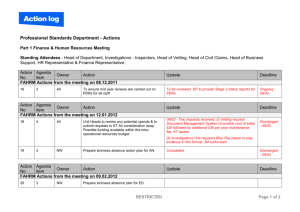

advertisement