CEO Tournaments: A Cross-Country Analysis of Causes, Cultural Influences and Consequences

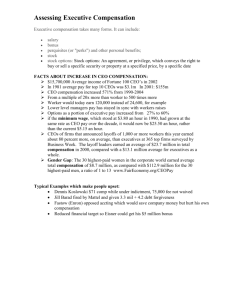

advertisement