Unveiled A Rhetorical Analysis of Street Artist Princess Hijab Ashley Coker

advertisement

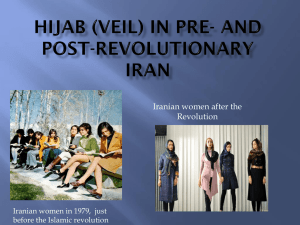

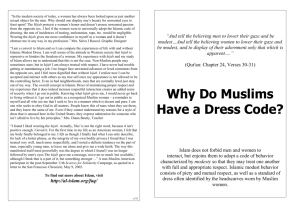

Unveiled: A Rhetorical Analysis ofStreet Artist Princess Hijab An Honors Thesis (HONRS 499) by Michelle Colpean Thesis Advisor Ashley Coker Ball State University Muncie, Indiana May 2012 Expected Date of Graduation May 2012 Abstract Princess Hijab is a graffiti artist and culture jammer whose work depicts figures in advertising fully or partially covered in Muslim veils. Her work employs both culture jamming to send a message to advertisers as well as political jamming in response to the French " burqa bans" that have been enacted to various degrees over the past decade. This paper analyzes Princess Hijab's street art through the lens of culture jamming, and draws critical implications regarding multiplicity within a rhetorical act, the hijab as a sliding signifier, and the use of ambiguity as a tool. 2 Acknowledgements I would like to thank Ashley Coker for advising me through this project. Her help during this particular task, as well as the support she has provided as an instructor, a coach, and a mentor, has been an integral part of my undergraduate success at Ball State. I would also like to thank Mary Moore for her assistance with the early construction of this project. Without her brain to pick, I'm not sure where I'd be. 3 Introduction Princess Hijab is France's most illusive street artist. She strikes at night with dripping black paint, slapping black Muslim veils, or hijab, on the half-naked airbrushed women and men of the Paris metro's fashion advertisements. She notoriously guards her anonymity, dressing in layers of clothing to disguise her identity and refusing to provide any details about her religious or political affiliation or even her true gender. Princess Hijab has "been on her veiling mission since 2006, but her project is taking on new meaning in light of France's push to remove burqas from public spaces," (Stewart, 2010). In fact, in secular republican France, there can hardly be a more potent visual gag than Princess Hijab's graffiti (Chrisafis, 20 I 0). These laws have not come without significant controversy - France's decision to ban Islamic face coverings from public spaces stirred global controversy - but public opinion polls have found that these laws are backed by 82% of the French people (CNN, 20 I 0). Considering the global audience Princess Hijab's graffiti has found and the current cultural transitions that are occurring in France, this French street artist offers a unique and complex contribution to this on-going debate. Given this, the present analysis will consider how Princess Hijab's graffiti simultaneously rhetorically disrupts both advertising and the French goverrunent's burqa ban. To proceed, the analysis will be guided by the rhetorical framework of Christine Harold's article "Pranking Rhetoric: 'Culture Jamming' as Media Activism," published in the September 2004 issue of Critical Studies in Media Communication. A framework of both culture jamming and political jamming is an appropriate lens through which to examine Princess Hijab's street art, as it takes into account the unique duality inherent in her work. In order to examine how Princess Hijab's graffiti functions rhetorically, we will first tum to previous relevant study, then examine her street art in depth, analyze her work through the lens of culture jamming, and finally draw some 4 critical conclusions and implications. Literature Review French Secularism and Lai"cite Lai"cite is, in its simplest form, is the notion of separating church and state. The basic premise of the concept is the removal of religious institution from government, as well as the converse removal of government from religious institution. French secular beliefs are far different than those upheld in the United States. Killian (2007) explains that while "secularism in the U .S. allows politicians to proclaim "God Bless America" as long as they do not name a particular God ... secularism in France makes any public reference to God anathema" (p. 309). Barras (2009) argues that the term "has never been defined clearly ... and thus can be invented with different meanings" (p. 1238). While a concrete definition is difficult to pin down, the sentiment of the term is well recognized. She goes on to state that lai"cite, "often referred to as the law of separation, regulates the status of religions in France by preventing the state from subsidizing or extending special recognition to any religion" (p. 1239). This state of French secularism is far more pervasive than the dominant American ideology, as has been reflected by recent legislative trends in France. In a December 17,2003 speech to the French public, then-President Jacques Chirac elaborated on the concept of la"icite, describing it as "the privilege place for meetings and exchanges, where everyone can come together bringing the best to the national community." He argued that rather than undermine religious belief, this secularist-driven neutrality in public space served to reinforce individual belief systems by allowing absolute freedom of choice. In Chirac's own words, "preserving neutrality can justify prohibiting any signs perceived as disrupting this 'coming together' of citizens" (Chirac, 2003). 5 Chirac's address preempted the 2004 law that served to ban the wearing of religious symbols in schools. An amendment to the French Code of Education, this law furthered the secularist belief that public spaces should remain in a state of religious neutrality. The law holds an outright ban on any "conspicuous" religious symbol in a state-sponsored educational institution, and makes no provisions based on particular religious affiliations. Despite the nonspecificity of the mandate, the law soon came under fire for banning the Islamic headscarf or veil. Activists and politicians alike supported the law by voicing particular support for the elimination of the Muslim veil, perceiving it as a threat to women's equality. Killian (2007) states that "feminist groups and politicians alike believed that banning religious symbols in school would take pressure off Muslim girls who are forced to wear the veil by their parents, by fundamentalist groups, or by peers who call them names and may even threaten girls violence against girls who do not veil" (p. 309). These targeted comments against the veil led many to believe (and perhaps rightly so) that the 2004 legislation was a conscious effort to specifically eliminate the headscarf in a public arena. Opponents to this law argued in favor of the religious rights of the Muslim girls who choose to wear the veil, as they would be forced between following the religious creed which mandates the veil for reasons of modesty, and attending their educational institution. With the introduction of current President Nicolas Sarkozy came stricter enforcement of the lalcite ideology through the banning of face veils in public places within the entirety of the country, effective in July of201O. Barras (2010) explains that with the passing of this legislation, the burqa "had become the antonym of Frenchness, lalcite, and the universal values it conveyed" (p. 230). The general French sentiment from both the public and policymakers alike fell in favor of the ban. According to Georgetown University's Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World 6 Affairs, the French National Assembly passed the "burqa ban" by a nearly unanimous vote, and with overwhelming support of the French public (France). Despite majority support in France, the law was seen by many to extend the problems introduced by the 2004 mandate, as an infringement on the rights of Muslim women and a threat to religious Freedom. Overall, la'icite is a convention that holds strong roots in French politics. Recent trends regarding conspicuous religious symbols, particularly the Muslim veil, have only served to reinforce this notion. While the majority opinion in France is in favor of these laws, many in the global community have viewed these policies a a heavy-handed attempt to stifle religious expression, and perhaps more dangerously as a form of anti-Muslim discrimination. Street Art Street art holds tremendous rhetorical value as it reflects individual ideologies held apart from (and often in opposition to) mass-mediated popular culture. Borghini, Visconti, Aderson, and Sherry (2010) explain street art as "a countercultural response to commercially or statistinduced alienation... a populist aesthetic, a consumerist critique, and an urban redevelopment project" (p. 113). As McCormick and Weiss (2002) argue, "public art, graffiti included, is a raw yet emotional demonstration of world views" (p. 128). The work of street artists can be telling of the sociopolitical climate in which the artist is submersed, and often provides a deeply subversive form of commentary on the surrounding culture. Borghini et. al. (2010) explicitly state, "rhetoric in both art and advertising is strictly influenced by the social context within which it originated" (p. 113). Therefore, context is highly important for both the street artist as well as the street art. Neef (2007) tracks the physical location of graffiti as it relates to the concept of place. She explains that graffiti is originally placed in "non-places," areas such as subway tunnels, blind walls, and pillars that "extend between identifiable, true loci" (p. 419). The 7 almost nomadic, transitive nature of the physical location, while on one level utilized for its visibility and human traffic, is in many ways indicative of the spirit of graffiti itself. But graffiti can take on new life and alternative meaning when removed from its original context, as has occurred with increasing frequency in recent years as the popularity of street art expands. As opposed to the city streets setting the boundaries of a naturally occurring "graffiti museum," placing street art within the walls of an actual museum or art gallery can create more artificial boundaries and can influence the perception of the work. Additionally, the internet has also played a role in reframing street art, as this medium presents the opportunity for a global audience, but at the same time threatens to reduce the perceivable ·contextual factors that may set the scene for the work (Neef, 2007, p. 422). Graffiti artists and their work are often portrayed in a simplistically dichotomous nature, either as criminals marring the landscape of the region, or as legitimate artists expressing a voice of dissidence. From a strictly legal perspective, graffiti must be acknowledged as a highly illegal form of vandalism, often staking claim on public property where it has no legal right to be. In contrast, many view the work of graffiti artists to be just that- art- and view graffiti as a valuable form of commentary on the contemporary world (Sliwa & Cairns, 2007, p. 74). Recent trends toward legitimizing the work of street artists can be seen through the popularity of artists such as Arron Bird or Banksy, whose artistic career has spurred an Academy Award-winning film. The increasing popularity and ongoing prevalence of graffiti has resulted in a unique relationship between street art and advertising. In many ways, street art and advertising sit as dichotomous entities: one seemingly reckless, individualistic, and driven by underground force, the other pointedly intentional, mass mediated, and derivative of consumerism and dominant cultural narratives. Borghini et. al. (2010) argue that this relationship may be far less adversarial 8 and more convergent, as street artists and advertisers may in some cases implement many of the same tactics as they construct their messages, albeit for different ends. Through their analysis, they examine a set of rhetorical practices employed by street artists that "not only reflect, but might also be used to shape commercial advertising in the near future," (p. 113). This particular relationship ties together two realms that previously sat in a state of opposition, and shows the further influence street art has on the world at large. Semiotics and the Muslim Veil Griffin (2009) defines semiotics as "the study of the social production of meaning from sign systems," or "the analysis of anything that can stand for something else" (p. 323). Or, as semiotics scholar Umberto Eco put it more broadly, "semiotics is concerned with everything that can be taken as a sign" (Eco, 1976, p. 7). This type of study encompasses the sign and how it is interpreted, which is often inclusive of a variety of readings. There is a relationship between the signifier, or what is being presented, and the signified, or what is being said by the signifier. The resulting sign, or combination of these two, is not always the same for every individual- our unique backgrounds and attitudes often shape how we read the sign. Much of the controversy surrounding the hijab in France is a result of the varying interpretations of the image of the hijab. The hijab is a polysemous sign that often elicits strong reactions for a variety of reasons, depending on the individual or group doing the interpretation. The Muslim headscarf symbolizes different things in the international, French, and Muslim communities- and interpretations vary not only between these groups but within them as well. The Arabic definition of the word "hijab" lends itself to ambiguity. Al-Munajeed (1997) explains "hijab" means "a shield" or "to make invisible by using a shield." While the notion of a shield 9 may lend itself to a symbol of protection, the notion of invisibility feeds the argument the headcovering as a symbol of oppression. The basis for the law lies in the notion that the veil is a "symbol of male oppression" and that "niqab-wearing women are bullied into it by their husbands," (Willsher, 2011). French feminists and parliamentarians, who view the veil as oppressive and the laws as a form of liberation from this overbearing, patriarchal practice, champion this popular argument. And by and large, this is a view shared by many ofthe French people, as the vast majority support it- a Pew Global Attitudes Project survey found that French citizens backed the law by a margin of more than four to one (CNN, 2011). Croucher (2008) examines perspectives of French Muslims on the hijab in the wake of the 2004 laws banning conspicuous religious symbols in schools. One young woman explains that the hijab makes her feel safe, as she roughly explains in English, "I not worry about people stare at my body because hijab." Another woman agrees with the first, but elaborates on the importance of the hijab as a form of protest, stating, " I think hijab much more important for protest and politics. Hijab give me and other women change to show we proud to be Muslim. 1 upset with France ... 1 have protest thoughts" (p. 199-200). In light of the 2004 ban, the hijab has gained another significant level of meaning as an expression of Muslim pride and a symbol of protest against the French government. Some Muslim women have not been deterred from wearing the hijab, but instead don the veil with a renewed fervor - not just for religious reasons but also in opposition to their perceived oppression by the French government. One young French immigrant explains the ban is a way of enforcing the social norms and eliminating religious diversity, stating, "The ban it to make 10 Muslim women be more like French Christian women. They want to control my body, mind, and my soul," (Croucher, 2008, p. 201). Background Artifact and Purpose Princess Hijab is an underground street artist operating in Paris, France. Her true identity is unknown, as she disguises herself under layers of clothing-- a wig, a spandex bodysuit, a free flowing cloak, long gloves-- as she travels through the Paris subway system with a large paint marker. She has attracted international attention with the graffiti she paints on subway advertisements, covering scantily clad men and women in Muslim veils with a messy paint marker. She calls this process "hijabisation" (Chrisafis, 2010). In this collection of work, Princess Hijab utilizes advertisements- often from major companies such as clothier H&M or Dolce and Gabana- in the Paris metro system. These walland poster-sized advertisements depict scantily clad people- individually, in groups, and both men and women. She then goes to work with a dripping black paint marker, covering the people in the advertisements in various ways with a traditional Muslim veil. Sometimes she covers only the face and neck, other times she covers the entire body, and in some instances she will cover most of the body but leaves only bare legs or stomach revealed. Upon the completion of each piece, Princess Hijab takes a high quality photograph, which allows the images to live a second life online (Chrisafis, 2010). Princess Hijab's artwork has captured international attention-- likely a combination of the striking nature of her work and the controversy surrounding the image of the Muslim veil in France. Her work is visually striking, but beyond that is the speculation as to what it means in the larger cultural context. Some view her street art as a commentary on advertising and societal 11 perception of women, "highlighting the hypocrisy of mainstream society's attitude to women's dress," (le Roux, 2010). She has kept mum in regard to the explicit meaning of her work, leaving the meaning open and up to interpretation by the viewer. Rhetor The persona of Princess Hijab is an ambiguous, manufactured identity. She explains to one blogger during an interview, "The real identity behind Princess Hijab is of no importance. The imagined self has taken the foreground, and anyway it's an artistic choice" (Agencies, 2010). She is as unwilling to directly reveal any information about her personal agenda as she is to divulge her true identity-- she leaves her art to speak for itself. Princess Hijab's anonymity is arguably as important as an established, known identity would be, as it grants additional depth and context to her work. The speculation surrounding her identity is widespread, as individuals and news outlets question whether she is a Muslim fundamentalist reinforcing the importance of hijab, a feminist speaking out about the portrayal of women in advertisement, some combination of the two, or something else entirely (Grace, 2010). Due to speculation based on her stature and mannerisms, some speculate that "she" may actually be a "he," as one blogger states after an interview, "It is more than likely that Princess Hijab isn't even a woman," as he describes her "husky voice" (Agencies, 2010). Context and Occasion Audience Princess Hijab's firsthand audience is comprised of the individuals who see her street art in the tunnels Paris subway system, the primary area where she operates. Due to the powerful controversy surrounding the image of the hijab in contemporary France, it makes sense that her artwork would be located in the busy Paris metro. However, her work has been granted 12 significant exposure online, and has subsequently captured international media attention. Her artwork, as well as the speculation as to its meaning and significance, has been featured by news outlets such The Guardian, Salon.com, The Mail and Guardian, and more. She has also taken advantage of the internet, with a select few images featured on a personal website and countless others circulated through blogs and news websites. A short six-minute documentary video of her in disguise documenting the process of creating new artwork has surfaced online as well, hosted by Babelgum and accompanying a short paragraph about the French burqa ban. This expands her audience to the global community, brining greater depth and diversity to the discussion and viewership of her work. Method Jamming The concept of culture jamming was introduced in 1985 by the band Negitaveland, on a cassette recording where one of the band members discussed a particular type of resistance against the present media environment, marked by reworking a billboard to subvert the message intended by the advertiser (Cammaerts, 2007, p. 71). Harold (2007) explains the term "culture jamming" is "based on the slang word 'jamming' in which one disrupts existing transmissions" (p. 192). Culture jammers act on an existing text and alter the message in a nuanced way to change the message of the rhetoric in its entirety, shifting the meaning from an often corporatelysponsored narrative perceived by the culture jammer as harmful, to a more satisfying end, critical of the original message. The act of culture jamming has been studied through a variety of lenses, from communications scholars, journalists, sociologists, and even the advertisers themselves (Carducci, 2006, p. 118). Sandlam and Milam (2008) argue that culture jammers often act in support of 13 counterhegemonic possibility, in an attempt to stifle the racism, sexism, homophobia, racism, and other damaging ideologies often present in mainstream popular culture (p. 330). Culture jammers practice the act in order to subvert messages from mainstream culture, particularly the capitalistic, consumerist messages of the corporate world. Culture jamming can occur through a variety of mediums; by distorting images in advertisements or billboards, engaging in acts of corporate sabotage, or otherwise reshaping the messages present in cultural communication. Culture jamming is not solely regulated to cultural commentary, but manifests in politics as well. Cammaerts (2007) argues that the act of culture jamming in itself is inherently political, as it "reacts against the dominance of commodification and corporate actors within society and everyday life," it is often conveyed as attacking "capitalist corporate brand culture" rather than pointedly attacking a specific political message (p. 72). Cammaerts presents the term "political jamming" as a means to describe the application of culture jamming techniques focused on explicitly political issues (p. 75). Although the technique and intention is much the same between culture jamming and political jamming, the focus of the act is politically motivated, and arguably more focused. Harold (2004) explains that culture jamming is "largely a response to corporate power," and "may not be as productive in rhetorical situations that call for legal or policy interventions," (p. 209). She suggests that in regard to her definition of culture jamming, it is regulated to actions that work in opposition to corporate establishment, and does not extend to more specific social and political issues. Thus, the focus of political jamming in particular is a separate jam from culture jamming as a whole. Another branch of culture jammers is described by Harold (2004) as the "prankster," an "alternative sort of culture jammer who resists less through negating and opposing dominant rhetorics than by playfully and provocatively folding existing cultural forms in on themselves" 14 (p. 191). Rather than working against the current of the original message, pranksters go with the flow in order to ultimately redirect the message to new ends that meet the prankster's intentions. She explains that crucial to the prank lies the "aha! " moment, where the prank is carried out or revealed to the audience- the moment where the newly formed picture comes to a head and the audience is forced to recognize the often dissonant messages present in the newly reformed material. Harold argues the legitimacy of the study of pranking rhetoric by stating, "the playful and disruptive strategies of the prankster have much to offer social justice movements," indicating the power of the message to represent the rhetor's counter-hegemonic belief system (p. 192). Why the spirit of a prank may often seem lighthearted, the message is not definitively so, and often reflects on important cultural commentary about pressing issues in the environment. The effectiveness of pranking rhetoric comes through the prankster's attachment to the success of commercial rhetoric. Commercial messages hold tremendous power over our purchasing decisions, attitudes, and beliefs, taking a pervasive hold in shaping our worldview. Harold (2004) explains, pranking takes its cue from "the incredible success of commercial rhetoric to infect contemporary culture" (p. 209). She goes on to explain that "mass-mediated pranks and hoaxes do not oppose traditional notions of rhetoric, but they do repattem them in interesting ways" (p. 207). By changing the existing elements of an existing text, pranksters are able to use the resources at hand and strategically augment them for their own uses. Pranking Rhetoric Harold's article deals specifically with pranking rhetoric, which she defines as a type of jamming that resists " less through negating and opposing dominant rhetorics than by playfully and provocatively folding existing cultural forms into themselves ... in an effort to redirect the resources of commercial media toward new ends" (Harold, 2004, p. 191). Specifically, three 15 tenets from Harold's article "Pranking Rhetoric: 'Culture Jamming' as Media Activism" can be used to analyze a prank as both an act of culture jamming and an act of political jamming. Harold suggests that through adornment, synecdoche, and ethos, a prank can gain rhetorical strength. First, pranking operates as rhetorical protest through stylistic exaggeration, or what Harold calls adornment. She explains that this involves adornment in "a conspicuous way that produces some sort of qualitative change," a change that is "produced not through reconfiguration of the object itself," (Harold, 2004, p. 196). Adornment augments a dominant mode of communication and therefore interrupts its conventional pattern. The prankster uses the medium created by the target, but disrupts the intended communication. For example, painting the word "WAR" on a stop sign changes its meaning entirely, but uses the recognizable nature of the stop sign as its launching point. Second, another important aspect of Harold's framework is synecdoche. Harold defines synecdoche as "an easy visual short hand" for a larger message (Harold, 2004, p. 201). The Greek translation of the word is "simultaneous understanding," meaning that given a part, you will be able to understand the whole. For example, by calling a business person a "suit," a person is referring only to a small, specific part of their wardrobe, but there is shared understanding that the person is referring to the business person as a whole. In the instance of culture jamming, she explains that synecdoche serves as a short hand for "a whole host of grievances against globalization's prevailing economic ideology," (p. 201). How the image functions as a symbol is integral to this process- how the image functions as a sign for a larger whole, how it is interpreted, and what if signifies. Finally, in a prank, unlike traditional rhetorical situations, the ethos of the rhetor is not at 16 the forefront of the rhetoric. Harold states that in a prank, the "effectiveness does not depend on the ethos or charisma of a specific rhetor. Hence, they fall outside the expectations of what conventionally qualifies as effective rhetoric," (Harold, 2004, p. 207). The identity of affiliations of the one doing the pranking is secondary to the prank itself. For example, not knowing who throws a pie in your face does not make the fact that you're been pied any more-- or less-- funny. Analysis In order to analyze Princess Hijab's graffiti through a dualistic perspective, it is important to establish its legitimacy as both a form of culture jamming and political jamming. Her work has been compared by many to other jamming movements and texts. Grace (2010) compares her graffiti to "a more cryptic sort of AdBuster culture jamming." Another news outlet explains that her work is "particularly French in its anti-consumerism and ad-busting stance" (Chrisafis, 2010). Princess Hijab's artwork has been easily identified by many as an act of culture jamming by viewers of her work. Additionally, Princess Hijab herself has stated that she has gained influence from other culture jamming texts, stating, "I'd read Naomi Klein's No Logo and it inspired me to risk intervening in public places, targeting advertising," (Chrisafis, 2010). She is heavily influenced by advertisement, and her work depends upon it to convey its message. The advertisement is the literal and figurative base of her work- her graffiti couldn't function the same way without it. But through her addition of the hijab, the message of the advertisement is transformed entirely. While many are quick to analyze Princess Hijab's graffiti solely as an act of culture jamming, there is an additional level of political message that is just as important. Given the hotbed of political controversy surrounding the image of the Muslim headscarf in contemporary France, her bold, black images of the hijab are heavy with political symbolism and importance. 17 Although Princess Hijab won't explicitly discuss the meaning of her work, her political affiliation, or affiliations with any other groups, one thing she is not shy about is her feelings toward the treatment of minority groups in France. She explains that her work extends beyond the image of the burqa itself, but speaks toward the larger issue of integration, assimilation, and the treatment of minorities in her country. She states in one interview, "If it was only about the burqa ban, my work wouldn't have resonance for very long. But I think the burqa ban has given a global visibility to the issue of integration in France" (Chrisafis, 2010). By using the hijab in her work, she is shining a spotlight on the controversial treatment of a minority group in France. By putting this image in a public place in France, she is outwardly defying the government with this act of protest. Chrisafis (2010) states, "In secular Republican France, there can hardly be a more potent visual gag than scrawling graffitied veils on fashion ads." Princess Hijab's graffiti is not just considered a gag in the popular sense, but a prank in the rhetorical sense as well. Harold's article explains that pranks "playfully and provocatively" fold existing cultural norms in on themselves to pull one over on the audience, resulting in an "aha" moment of realization when the prank is realized. Princess Hijab's graffiti fulfills all of these actions. She uses a messy black paint marker as a means of enacting her protest-- nothing violent or radical, but instead an almost childlike tool. She plays with existing advertisements, folding present advertising tropes such as bare skin into something different, and adding layers of cultural commentary in the process. Her prank definitely results in an "aha" moment, when passers-by look at the walls, expecting to see the normal advertisements lining the walls of the subway tunnels, and are instead confronted with Princess Hijab's veiled images. Harold's framework can be used specifically to explore Princess Hijab's framework as 18 both an act of culture jamming and an act of politically jamming. Through her use of adornment, synecdoche, and ethos, we can examine how her street art effectively functions to provide cultural commentary. The first strategy pulled from Harold's article on pranking rhetoric is adornment. In relation to advertising, Princess Hijab quite literally uses this rhetorical strategy while pranking advertisers by painting a black hijab over existing advertisements in the Paris subway system. Take for example an H&M advertisement, originally depicting two young models in bikinis (See appendix, Image 1). Here Princess Hijab maintains the sexualization of the women by leaving a large portion of their abdomens uncovered, but adorns their faces and lower legs, while leaving the logo untouched for passers by to read. The art is not starting from scratch, but rather takes an existing medium, an advertisement placed in a highly trafficked area, and alters its intended purpose. Instead of using attractive women (and their bodies) to sell swimsuits, the viewer is now faced with an additional layer to sift through, which causes them to re-evaluate the image and see it in a different light entirely. In relation to the political, Princess Hijab's pranks occur in very public places, thus she pranks the French government's laws against wearing the Muslim veil in public. She alters an image of two women depicted in what is likely a public place- a beach. The image itself is also located in a public place- within the tunnels the Paris subway system, where countless Parisians under the rule of this law will constantly pass by. Thus, she takes the taboo image of the hijab and uses it in a highly public way, thus symbolizing open defiance of the ban. Second, pranksters use synecdoche, or an easy short hand for a larger message. In relation to advertising, the "hijabisation" represents the commodification of a human body. Princess Hijab often leaves most of the body untouched, but covers the most personal feature - the face. 19 Thus, one could easily read the prank as speaking to a larger critique of the sexualization and commodification of women. In some ways, this speaks to a traditional reason the hijab is worn by Muslim women-- a barrier between a woman's body and her surroundings, providing feelings of safety and a sign of modesty. Even if not taken this far, it still serves to highlight the rampant sexualization of imagery that is present in advertising, and turns it on its head to highlight its ridiculous nature. In relation to the political, the hijab is undoubtedly a loaded image. Princess Hijab has stated that the veil "has many hidden meanings, it can be as profane as it is sacred, consumerist, and sanctimonious ... the interpretations are numerous and of course it carries great symbolism on race, sexuality and real and imagined geography" (Stewart, 20 10). The hijab is polysemous, holding a number of meanings depending on the audience at hand. Take for example a Dolce and Gabana advertisement, depicting a number of young men (See appendix, Image 2). Princess Hijab has this time targeted an advertisement featuring exclusively men, clad only in their brand name underwear. For some of the men, she covers only their faces, but others have their bodies covered to varying degrees as well. Here, outside critics have offered multiple readings for the image: the hijab as oppressive to genders, to wear or not wear something is ludicrous regardless of who is enforcing the rule, the veil as ridiculous and dictatorial, or even that the veil can be weirdly sexy. There is no doubt that the veil hangs heavy with symbolism, but what exactly is being symbolized is ambiguous and open to interpretation depending on the viewer. Whatever the intent, the symbol is striking because it is loaded. Finally, unlike most traditional messages, in a prank the credibility of the source of the message is not at the forefront of the rhetoric. Rather, the action or the prank takes precedence and serves as the true focal point. Like many graffiti artists, Princess Hijab goes to great lengths 20 to keep her identity a secret, covering every inch of her body by wearing gloves, tights, elaborate robes, and a dramatic hairpiece (see Appendix, Visual 3). Despite pressure from her fans as well as media outlets, she (or possibly, he) has revealed nothing about her identity, even in interviews, which are frequently conducted only through the internet. In regard to her true identity, she states, "People have the right to ask me questions about my identity. But I'm anonymous: the answer's just not a part of my art" (Grace, 20 I 0). Because we are unaware of her ethnicity, gender, occupation, religion, or heritage, the ethos of the rhetor is suspended entirely. All we know of the rhetor is the little identity she has crafted and the small bits of cryptic information she has revealed in interviews. This suspension of ethos makes the prank, and thus the message against both advertisers and the French government, that much stronger. So little information can be gained that the majority of the attention is left to the prank itself, and speculation about what it means in regard to both advertising and French politics. Conclusions and Implications Through her graffiti, Princess Hijab jams cultural messages from advertisers as well as political messages from the French government. Because her art distributes the intended message and demonstrates Harold's criteria- including adornment, synecdoche, and ethos- her art is dually disruptive. From this analysis are implications on both pranking multiple entities as well as the power of the sliding signifier. First, through this analysis it becomes apparently that Princess Hijab's graffiti successfully functions as rhetorical protest against multiple trends in contemporary French culture, no matter her intentions. Bitch Magazine explains that Princess Hijab's work has gained international notice particularly because it "wreaks artistic revenge" on the dual constructs of advertising and social prejudice," (2009). In essence, Princess Hijab's artwork is the rhetorical 21 equivalent of killing two birds with one stone-- and in this case, it is these dual constructs that give her message such tremendous rhetorical might. Princess Hijab's intentions in regard to her artwork at as mysterious as her true identity. In interviews, she is consistently cryptic about what her work means and what she is trying to say through it. The fact that she won't provide a concrete explanation and that she provides no real identity from which to extrapolate her cultural or political beliefs only adds to the speculation and various interpretations of her work. Princess Hijab's graffiti began to attract international media attention around 2010, about the same time France's proposed ban of the burqa in all public areas was being seriously deliberated and eventually made into law. However, she explains in an interview that she painted her first graffiti veil in 2006, "the 'niqabisation' of the album poster of France's most popular female rapper, Diam" (Chrisafis, 2010). While this could still be viewed as a response to French secularism, perhaps in regard to the 2004 laws banning the burqa in schools, it is clearly not in direct response to the most recent law, as it is often framed. When prompted about the meaning of her work, Princess Hijab states, "I used veiled women as a challenge," an ambiguous answer that brings a viewer of her work no closer to establishing her intended meaning (Chrisasfis, 2010). In fact, with this comment she disregards her own work involving veiled men- a section of her work often ignored by media outlets as well. The dynamic, multifaceted nature of her work seems to throw off many as to her true intentions, but at the same time, is part of what makes her message so powerful. Regardless of her intentions (or at least the intentions she is willing to disclose), her work does function as both culture jamming and political jamming, and this duality adds to the impact of both messages. Second, Princess Hijab's graffiti function as a sliding signifier. French psychoanalyst 22 Jacques Lacan's famous essay, "The Agency of the Letter in the Unconscious or Reason Since Freud," introduced the notion of sliding signifiers (1977, p. 150). With a sliding signifier, a sign is capable of becoming detached from its conventional signifier and contributing to a new constellation of meanings. The original, intended, or conventional meaning of the symbol can be changed or expanded to include a more relevant cultural interpretation based on the societal repercussions it has come to signify. As Lacan puts it, the "classic yet faulty illustration by which its usage is normally introduced," enters the signified in a form which "raises the question of its place in reality" (p. 150-151). To illustrate this point, Lacan uses the example of public Western bathrooms-- two doors, one marked with a silhouette of a woman, and the other marked with the silhouette of a man. Lacan argues that with these symbols, an "unexpected precipitation of an unexpected meaning," occurs (Lacan, 1977, p. 151). The original denotative meaning ofthe male and female silhouettes is obviously to indicate which sex is supposed to use which bathroom. However, Lacan explains that the meaning of these signs have been expanded to include a larger societal meaning that they implore. In this instance, he states that the image of the figures on these separate doors "symbolizes, through the solitary confinement offered Western Man for the satisfaction of his natural needs away from home, the imperative that he seems to share with the great majority of primitive communities by which his public life is subjected to the laws of urinary segregation" (p. 151). The sign becomes larger than its original meaning-- the intended gender for each public restroom-- and is expanded to include the realities of culture-- gender division, socialization, and even reigning in our feral instincts. In a keynote address to the French parliament, French President Sarkozy asserts, "the burqa is not a religious symbol, but a sign of the subjection, of the submission of women" 23 (Carvajal, 2009). Public opinion polls suggest that Sarkozy's interpretation of the hijab is the conventional reading in France, but not the international community. In fact, two out of three Americans would oppose such a ban (CNN, 20 11). As the BBC explains in regard to Turkey's regulation of Muslim veils, "the Islamic headcovering has become a divisive symbol," without conventional meaning. It is this process, the sliding of the signifier, that makes both France's new law as well as Princess Hijab's artwork particularly noteworthy. Finally, Princess Hijab's work uses ambiguity and absurdity as a rhetorical tool. Obviously, the hijab itself is an ambiguous symbol, open to interpretation for a variety of meanings. Several aspects of her street art are indefinite, obscure, and sometimes even contradictory. She covers the bodies of models with a black hijab, but leaves large portions of their bodies uncovered. She goes through great lengths to conceal her identity, but has provided interviews to media outlets. And within these interviews she agrees to, she often provides very little information about the meaning of her work. Contradictory rhetoric in response to the French burqa ban is not unique to Princess Hijab. Chrisafis (2010) reports that "two French women calling themselves 'niquabitch' reproduced the classic visual mixed metaphor of walking around central Paris in niqabs, black hotpants, bare legs, and high heels, posting a film of it online in order to highly the 'absurdity' of the ban." Princess Hijab's work reads similarly in many instances, covering up some parts of the body while leaving others untouched. This contradictory, juxtaposed imagery, of modesty and coverage against exhibitionism and bareness, creates a feeling of dissonance in the viewer. The ambiguity in her work is reflective in many ways of the issues surrounding the hijab. Groups in favor of and against the ban claim that their stance reflects human rights: those in favor of the ban argue it helps free women from subjugation, and those against the ban argue 24 they are in favor of religious freedom and individual expression. For many, this issue isn't entirely clear cut-- it is as ambiguous as Princess Hijab's artwork would imply-- there are many layers to the controversy. The ambiguity Princess Hijab utilizes in her imagery as well as her persona leaves her street art open to interpretation-- drawing attention to the issues of exploitation in and pervasiveness of advertising as well as the burqa ban and treatment of French minorities, but also creating room for further discourse about individual interpretation of the material, just as people are likely to have individual opinions on each of these subjects. 25 References Aburawa, A. (2009). Veiled threat. Bitch Magazine. Retrieved from http://bitchmagazine.org/artic1e/veiled-threat Al Munjajeed, M. (1997). Women in Saudi Arabia today. New York, NY: St. Martin's Press. Agencies. (2010). Graffiti artist mocks burqa ban: Princess Hijab targets half-naked fashion ads in France's metro. Mid Day. Retrieved from http://www.mid-day.comlnews/ 201 0/novl13111 O-Princess-Hijab-Targets-half-naked-fashion-France-Metro.htm Barras, A. (2009). A rights-based discourse to contest the boundaries of state secularism? The case of the headscarfbans in France and Turkey. Democratization, 16(6), 1237-1260. Barras, A. (2010). Contemporary laYcite: Setting the terms of a new contract? The slow exclusion of women wearing headscarves. Totalitarian Movements and Political Religions, 11 (2), 229-248. Borghini, S., Visconti, L. M., Anderson, L. , & Sherry, J. F. (2010). Symbiotic postures of commercial advertising and street art: Rhetoric for creativity. Journal ofAdvertising, 39(3),113-126. Cammaerts, B. (2007). Jamming the political: Beyond counter-hegemonic practices. Journal of Media and Cultural Studies, 21(1), 71-90. Caravjal, D. (2009). Sarkozy backs drive to eliminate the burqa. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.coml2009/06/23/world/europe/23france.html Carducci, V. (2006). Culture jamming: A sociocultural pespective. Journal of Consumer Culture, 6, 116-l32. Chirac,1. (2003). Chirac on the secular society. BBC News. Retrieved from http://news. bbc.co. uk/2/hi/europe/3 3 30679 .stm 26 CNN Wire Staff. (2011). France's burqa ban in effect next month. CNN World. Retrieved from http://articies.cnn.comJ20 11-03-04/world/france. burqa.ban_1_burqa-ban-full-face-veil? s=PM:WORLD Chrisafis, A. (2010). Cornered: Princess Hijab, Paris's elusive graffiti artist. The Guardian. Retrieved from http://www.guardian.co.uklartanddesignl20 1O/novllllprincess-hijabparis-graffiti-artist Croucher, S. M. (2008). French-Muslims and the hijab: An analysis of identity and the Islamic veil in France. Journal of Intercultural Communication Research, 3 7(3), 199-213. Eco, U. (1976). A Theory ofSemiotics. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. France. Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs at Georgetown University. http://berkleycenter.georgetown.edulresources/countries/france Grace, J. (2010) Peeking behind the veil: Princess Hijab. Hyperallergic. Retrieved from http://hyperallergic.comJ8417 Ipeeking-behind-the-veil-princess-hijabl Griffin, E. (2009). A First Look at Communication Theory. New York, NY: McGraw Hill. Harold, C. (2004). Pranking rhetoric: "Culture jamming" as media activism. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 21 (3), 189-211. Head, J. (2010). Quiet end of Turkey's college headscarfban. BBC News. Retrieved from http://www.bbc.co.uklnews/world-europe-11880622 Killian, C. (2007). From a community of believers to an Islam of the heart: "Conspicuous" s ymbols, Muslim practices, and the privatization of religion on France. Sociology of Religion, 68(3), 305-320. Lacan, J. (1977). The agency of the letter in the unconscious, or reason since Freud. Ecrits: a Selection. London: Tavistock. 27 Le Roux, M. (2010). From burqas to bikinis. Mail and Guardian. Retrieved from http://mg.co.za/article/201 0-12-17 -from-burqas-to-bikinis Neef, S. (2007). Killing kool: The graffiti museum. Art History, 30(2), 418-431. Sandlin, 1. A. & Milam, 1. L. (2008). "Mixing pop ( culture) and politics": Cultural resistance, culture jamming, and anti-consumption activism as critical public pedagogy. Curriculum Inquiry, 38(3),323-350. Sliwa, M. & Cairns, G. (2007). Exploring narratives and antenarritives of graffiti artists: Beyond dichotomies of commitment and detachment. Culture and Organization, 13(1), 73-82. Stewart, D. (2010). The controversial persona and artwork of Princess Hijab. lezebel. Retrieved from http://jezebel.coml5687564/the-controversial-persona--artwork-of-princess-hijab Willsher, K. (2011). "Burqa ban" in France: Housewife vows to face jail rather than submit. The Guardian. Retrieved from http://www.guardian.co.uk/woridl20111apr/l0/france-burqalaw-kenza-drider 28