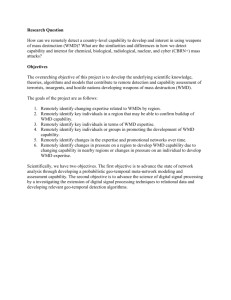

Human Behavior and WMD Crisis /Risk Communication Workshop

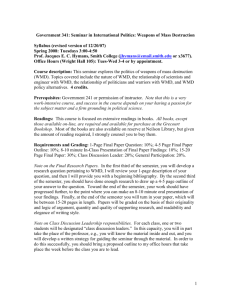

advertisement