THE ROLE OF EMPOWERMENT IN HEART FAILURE AND ITS EFFECTS... SELF-MANAGEMENT, FUNCTIONAL HEALTH, AND QUALITY OF LIFE

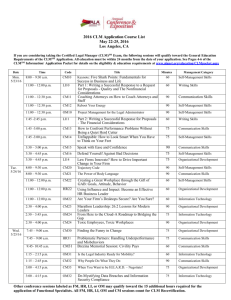

advertisement