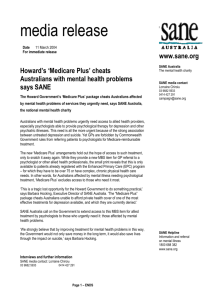

About This Bulletin

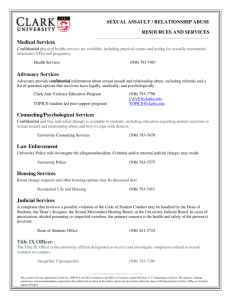

advertisement