EFFECTS OF GROUP MUSIC THERAPY ON PSYCHIATRIC PATIENTS: A RESEARCH PAPER

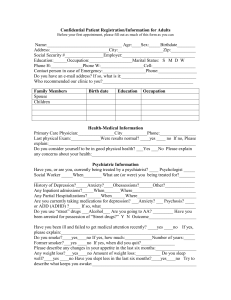

advertisement