EFFECT by May Donald Hughes Shaw

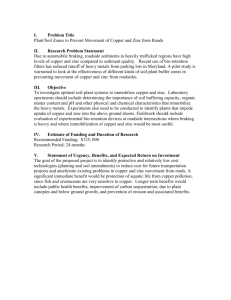

advertisement