DRAFT Experimentation and Collaboration to Enhance Employment for Persons with

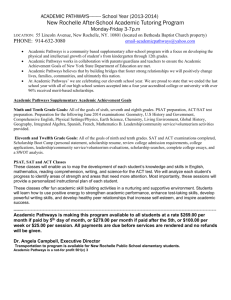

advertisement