The Economics of Amenities and Migration in the Pacific Northwest:

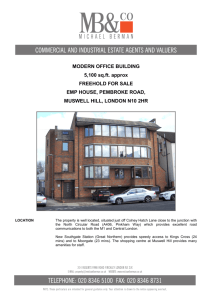

advertisement