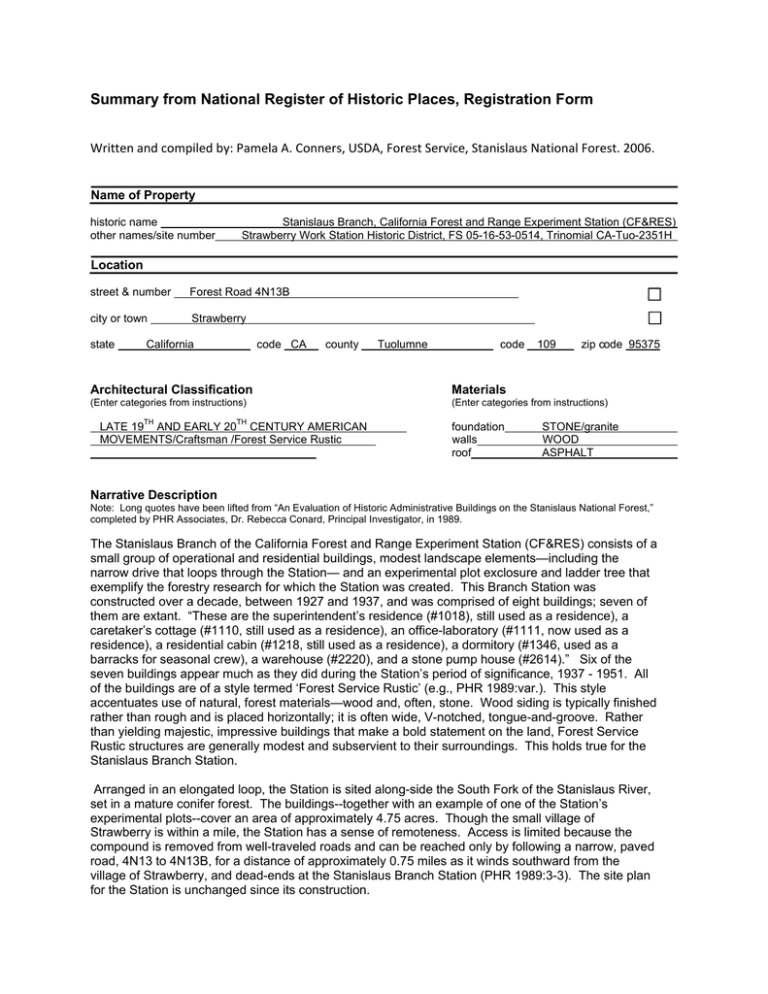

Summary from National Register of Historic Places, Registration Form

advertisement