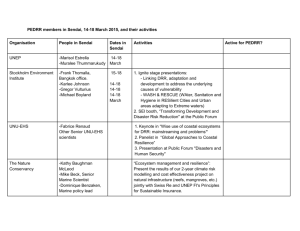

Characteristics of Disaster- nity

advertisement