Medication Concepts, Records, and Lists in

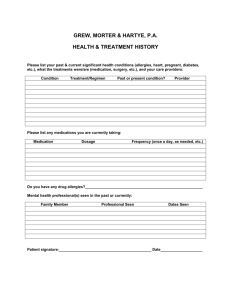

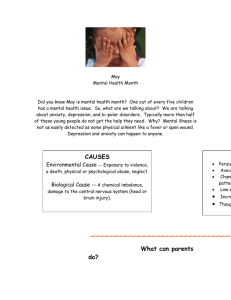

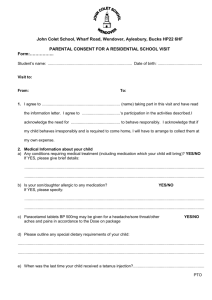

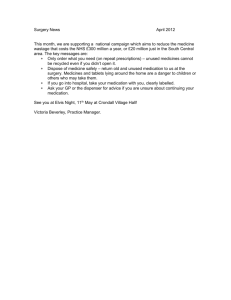

advertisement