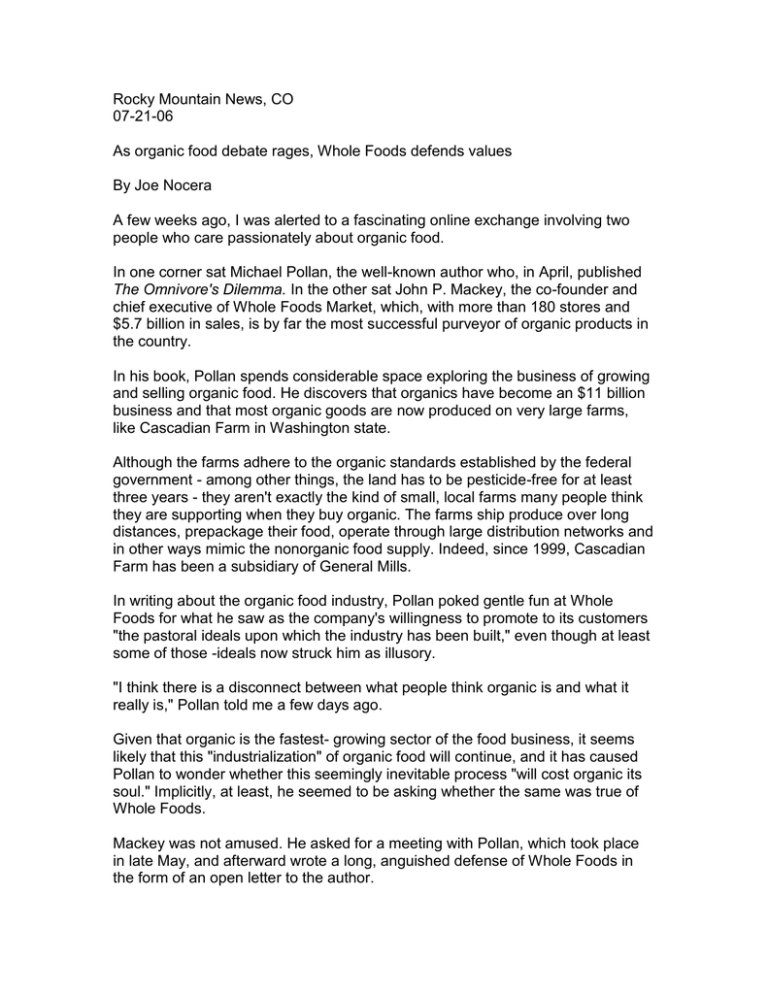

Rocky Mountain News, CO 07-21-06

advertisement

Rocky Mountain News, CO 07-21-06 As organic food debate rages, Whole Foods defends values By Joe Nocera A few weeks ago, I was alerted to a fascinating online exchange involving two people who care passionately about organic food. In one corner sat Michael Pollan, the well-known author who, in April, published The Omnivore's Dilemma. In the other sat John P. Mackey, the co-founder and chief executive of Whole Foods Market, which, with more than 180 stores and $5.7 billion in sales, is by far the most successful purveyor of organic products in the country. In his book, Pollan spends considerable space exploring the business of growing and selling organic food. He discovers that organics have become an $11 billion business and that most organic goods are now produced on very large farms, like Cascadian Farm in Washington state. Although the farms adhere to the organic standards established by the federal government - among other things, the land has to be pesticide-free for at least three years - they aren't exactly the kind of small, local farms many people think they are supporting when they buy organic. The farms ship produce over long distances, prepackage their food, operate through large distribution networks and in other ways mimic the nonorganic food supply. Indeed, since 1999, Cascadian Farm has been a subsidiary of General Mills. In writing about the organic food industry, Pollan poked gentle fun at Whole Foods for what he saw as the company's willingness to promote to its customers "the pastoral ideals upon which the industry has been built," even though at least some of those -ideals now struck him as illusory. "I think there is a disconnect between what people think organic is and what it really is," Pollan told me a few days ago. Given that organic is the fastest- growing sector of the food business, it seems likely that this "industrialization" of organic food will continue, and it has caused Pollan to wonder whether this seemingly inevitable process "will cost organic its soul." Implicitly, at least, he seemed to be asking whether the same was true of Whole Foods. Mackey was not amused. He asked for a meeting with Pollan, which took place in late May, and afterward wrote a long, anguished defense of Whole Foods in the form of an open letter to the author. His essential point was that Whole Foods was a company deeply committed to the set of values associated with organic farming, including sustainability and the environmental benefits of decreasing the use of pesticides. He defended the company's reliance on its regional distribution centers as an important means of meeting customer demand. Indeed, he pointed out, the increased demand for organic food was in large part due to the efforts of Whole Foods. He listed some of the things the company did that proved Whole Foods was not just another rapacious corporation - for example, its animal compassion program. "Whole Foods Market," he concluded, "is one of the 'good guys' in this story about the 'industrialization of agriculture.' " Like most people in my demographic group, I greatly enjoy shopping at Whole Foods. But until I'd read the exchange, I'd never really thought much about organic food as a business. After a little investigation, though, I think I now understand why Whole Foods is such an appealing store for so many people and why it's so important for Mackey to have his company viewed as one of the good guys. As corporations go, Whole Foods is the most interesting of beasts. On the one hand, it is a classic Wall Street darling, with rapid expansion, double-digit growth and a business model that no competitor seems able to touch. In presentations to investors, its executives speak of the importance of return on invested capital and how they plan to double annual sales to $12 billion by 2010. Its stock has returned more than 2,700 percent since it went public in 1992. Indeed, the Wall Street analysts I spoke to couldn't say enough good things about Whole Foods. "It is one of the best businesses in retail today," said John Heinbockel of Goldman Sachs. On the other hand, Mackey and his executive team make no bones about the fact that shareholders rank low on their list of priorities. They speak instead about the importance of keeping customers happy and employees engaged - and sticking to the company's core values. "We are a mission-driven company," Walter Robb, the company's co-president and chief operating officer, told me. Last year, in an article in Reason magazine, Mackey argued that making customers happy was far more important than maximizing profits. He also added a far more radical note: He believed in a form of capitalism, he said, "that more consciously works for the common good instead of depending solely on the 'invisible hand' to generate positive results for society." A values-driven capitalism, in other words. Although Mackey declined to be interviewed - and although I should point out that he is virulently anti-union - I have no doubt that he and the rest of the management team believe deeply in what they're saying. But I couldn't help notice that such an approach also happens to mesh very nicely with the business Whole Foods is in. "This is a values-driven market," said Frederick L. Kirschenmann, a distinguished fellow at the Leopold Center for Sustainable Agriculture at Iowa State University. Studies show that two-thirds of American consumers want to buy food that is consistent with their values, he told me. "They want superior products in terms of health, taste and nutrition." And Whole Foods' well-heeled customers are willing to pay for that food, which is one reason the company can command a premium on all its products, not just its organic fare. "The appeal of Whole Foods is that it is a place where food is celebrated, food is romanced, food is presented in a fashion that is in opposition to how it is sold in the vast majority of supermarkets," said Bill Bishop, the president of Willard Bishop Consulting, a food retail consultant. Organic goods are a crucial component of that "differentiation," he added, because the very term has acquired a kind of magical aura - a halo effect, in which the customer feels virtuous just by walking into the store. What, for instance, is the biggest selling organic product? Milk. Why? Because mothers want to do everything they can to ensure their children are healthy - and they believe that organic milk is healthier than ordinary milk. Many other people gravitate to organic food because they are environmentalists. Others believe strongly in sustainable farming, or the humane treatment of animals. Still others simply care about food that is fresher and tastier. That's a virtue, too. All of these are values Whole Foods conveys to its customers. So is it any wonder that Mackey got his back up when he read The Omnivore's Dilemma, with its suggestion that by doing so much of its business with large farms, Whole Foods was diluting the virtues of organic food? (Among his other points, Pollan writes that when, say, asparagus is shipped to Whole Foods from New Zealand, that is neither an example of sustainable agriculture nor fresh produce - nor is it even particularly environmental, given the fuel involved in getting it to the other side of the world.) Clearly, if your customers are coming into your store because they want to buy products consistent with their values, then being viewed as a good guy is absolutely crucial to your business. Whole Foods doesn't just sell food, it sells virtue. "It is aspirational retailing," Robb told me, and he's right. The minute people start viewing it as just another supermarket, the halo effect will disappear, and they'll gravitate to some other store that is more in tune with their aspirations. And hence, Whole Foods' difficulty in conceding that as it has grown up - and with it, the entire organic food industry - it has had to accept some compromises along the way. "Are there trade-offs?" Robb asked. "I suppose there are." But he quickly added that the company had already begun examining its practices and was working to improve them. "We are constantly raising the bar," he said. For instance, he pointed out, Whole Foods had recently stopped selling lobster because it didn't think the way they were treated was in sync with its views on animal compassion. Which brings me back to Mackey's exchange with Pollan. Pollan responded to Mackey's letter with a post of his own, in which he emphasized that the company had largely turned its back on local organic farmers. Mackey, in turn, wrote another lengthy letter in which he defended the company's record in dealing with local farmers - but he also vowed to do better. And sure enough, he has. The company is now allowing its store managers to do business directly with more local farmers and is also putting aside $10 million, which will be used to make small loans to local farmers. Will it be more expensive to work directly with farmers instead of routing everything through the regional distribution center? Of course it will. But for Whole Foods, no money will ever be better spent.