WorkHotel

by Alexander M Dixon

Bachelor of Philosophy in Architectural Studies

Bachelor of Science in Psychology

University of Pittsburgh, 2009

Submitted to the Department of Architecture

in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the

degree of Master of Architecture at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

February 2014

© 2014 Alexander M Dixon. All rights reserved.

The author hereby grants to MIT permission to

reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and

electronic copies of this document in whole or

in part in any medium now known or hereafter

created.

Signature of Author:

Department of Architecture

January 16th, 2014

Certified By:

Nader Tehrani

Professor of Architecture

Thesis Advisor

Accepted By:

Takehiko Nagakura

Chair of the Department Committee on Graduate Students

002

Committee

Nader Tehrani

Professor of Architecture & Department Head

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Joel Lamere

Assistant Professor of Architecture

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

William O’Brien Jr.

Assistant Professor of Architecture

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

003

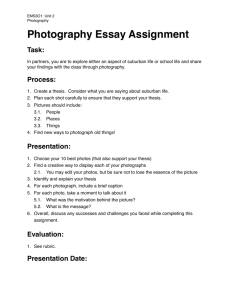

WorkHotel

by Alexander M Dixon

Submitted to the Department of Architecture on January 16,

2014 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of

Master of Architecture.

Abstract

The office has for decades been touted as a model of flexibility,

the super-generic shell facilitating the ultra-customized fit

out. However, as technology fuels a de-territorialization of the

workplace and employees are untethered from their desks,

the definition of flexibility must be rewritten architecturally

beyond furniture systems, organizational methodologies or

leasable space to encompass, and even prioritize, the potential of

productive geographies over a singular workplace. Accelerated

by the burgeoning sharing economy, increased telecommuting

and pervasive, these new working territories extend to public

and private institutions alike, challenging our present concepts

of ownership and demanding a re-interpretation of the office

typologically. This thesis sets out to take on that challenge, and

re-imagines the office through the lens of the hotel, mapping the

broader attributes of our contemporary working culture onto the

hospitality industries highly calibrated temporal management

system in a bid to displace the outmoded workplace with a new

typological model, the WorkHotel. Engaging the growing trend of

decentralization, the proposal seeks to create a platform for the new

urban working culture, embracing globalization and the necessity

of distributed workforce models. As a typological synthesis, the

project speculates on how productive overlaps between the office

and hotel reveal new opportunities for optimization through

architectural strategies, while at the same time questioning

our prevailing cultural distinctions between productivity and

relaxation, work and play, and the inherent spatial manifestations

that these concepts create.

Thesis Supervisor: Nader Tehrani

Title: Professor of Architecture

004

005

006

Acknowledgements

To the MIT faculty, I would like to thank you all for providing a

challenging and exciting 3.5 years, it has been a great experience

to be part of such an evolving and unconventional institution.

To my fellow students, it has been an amazing time getting to know

each of you and I can only hope you all have learned as much from

me as I have learned from you.

To Liam and Joel, for your spot on critiques and contribution to

my overall education.

To Nader, for never letting me get away with it.

To my parents, thank you for just about everything.

To Feifei, thank you for everything else :)

007

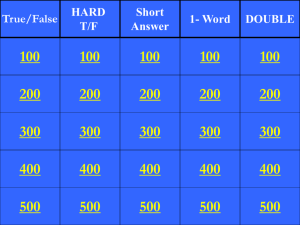

Contents

Introduction

The Desk

The Office

The WorkHotel

Appendix A: Thesis Defense

Appendix B: Model Photos

Appendix C: Alternate Experiments

Bibliography

List of Illustrations

008

010

028

052

082

088

094

114

118

008

Introduction

The WorkHotel

“In the past the man has been first,

in the future the system must be first.”1

- Frederick Winslow Taylor, 1911

Taylor’s quote, written over a century ago, signifies the beginning of the office’s inextricable

synthesis of technology and architecture, at times

symbiotic and at others reactionary. Historically,

the office has evolved along both paths, but in its

current state suffers from a lack of architectural

invention that matches the advances on the technology front, continuing to endorse a simple generic fit-out typology that has been the standard

for the past 50 years.The changing demographics

as millennials replace the baby boomers, physical

to digital and now ephemeral storage systems, the

evolution of organizational structures; all have

significant architectural implications that have

yet to be explored on a fundamental level. The

opportunity to work anywhere electricity and

wifi are prevalent provides a whole new staging

ground for the design of our future working culture, compared to 25 years ago when corporate

compartmentalization flourished and the cubicle

was at its height. The outgrowth of co-working

spaces, coffee shops and other public venues as

viable alternatives to the office suggest a shift away

from the dedicated centers to a more distributed

model of working spaces. This thesis challenges

the very notion of the office, and ultimately suggests that the future of the workplace is not in the

office, but rather, will be developed as a service

attached to other typologies, such as the hotel.

1

An analytical history of the office yields two intersecting but discrete trajectories: the interior

configurability of office systems furniture and the

prototypical shell building, which over the past

50 years have become married in the conventional office tower that currently occupies much

of our urban environments. A survey of more

contemporary (some might even say ‘progressive’) offices such as those operated by Google

demonstrates a tendency to offer fixed spatial

variability over systemic configurability, dedicating on average 25 percent of their workplace to

shared common areas, amenities, cafes, meeting

rooms and lecture halls. However, their strategies

still privilege the horizontal, and fail to mitigate

the vertical segregation that the stacked tower

type provides, continuing to abide by the unspoken rule of a fixed location in an urban center.

Changes in managerial organization and corporate structures in many companies are gradually

loosening the hold on employees, allowing them

geographic freedom provided they complete

their delegated responsibilities, but these changes

have yet to translate directly into an architectural

paradigm. Consequently, however, the evolution

of company ideologies are giving rise to what

might be thought of as a work sequence, rather

than a workplace, where employees can tailor

their lifestyle around various working locations the home, the office, the coffee shop, the library,

the lobby - complementing the range of different tasks required of the knowledge worker in our

contemporary economy.

Taylor, Frederick W. The Principles of Scientific Management. New York: Norton,

1967. Page 2.

009

Following the recent innovations in car, bike and

spare room rentals - ZipCar, bike shares and

AirBnB - all of which harness a digitized management platform to create new economies derived from existing underutilization, this thesis

explores how a similar decentralization of the office can not only produce new models of working, but how the technologically enabled mobility of the millennial workforce inherently changes

the current workplace from a ‘place’ to ‘geography.’ Short term rental models have already begun to spring up across the country, known as

co-working spaces, and often housed in conventional office buildings. The spaces provide

desks for individuals or groups on daily, weekly

or monthly bases, offering an alternative to the

three plus year leases commonly expected from

management companies while at the same time

providing a communal atmosphere. Drawing on

the success of the co-working spaces in the past

few years, the thesis proposes to push even further the temporal aspect of our nascent working

culture, embedding the elements of the office

within a new context, that of the hotel. Overlaying the distinct use-time parameters present

in the office and hotel, it is clear that both suffer from an underutilization of space: the office

during the night and the hotel during the day.

On an architectural level, the thesis seeks to conceptually reformulate the office as an infrastructure within the hotel model by developing an

organizational logic that functions at the global

2

scale of the building, distributing the prototypical elements of the office and hotel vertically as

a continuous, traversable environment, establishing a multiplicity of circulatory connections. Instead of regularized floors that are modified by

a potential client, the program is re-conceived

for a building as a service, and trades the initial

configurability of the past for the mobility of the

present and future. Creating a variety of zones

with different properties that are linked throughout the building, the nomadic worker can move

between areas in order to ‘reconfigure’ their own

environment through their own volition. Catalyzing the growing mobility of the workforce, the

rise of contract workers, startups and satellite offices, the thesis proposes to re-define the office

not as a singular, static destination but as a component in the urban framework, an infrastructure

for working, which in turn re-defines the hotel

not only as a place for rest and relaxation, but as

a productive space on a compressed time scale.

The juxtaposition of office and hotel, of work

and leisure, establish new situations akin to Tschumi’s notion of crossprogramming2, where a

“confusion of genres” takes place, engaging the

surreality of moving between environments that

have become optimized for nearly every part of

living and working, but on the scale of an afternoon, an evening or a three day weekend. The

hotel becomes the backbone for the new workforce, the operative medium for the deterritorialization of the office, and in turn is transformed

into a hybrid typology, the WorkHotel.

Tschumi, Bernard. Architecture and Disjunction. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press,

1996. Page 255.

010

The Desk

A Visual History

011

012

013

1904: Larkin Building

014

015

1961: Chase-Manhattan Bank

016

017

1963: Osram Offices (Burolandschaft)

018

019

1969: Action Office II

020

021

1980s: Cube Farm

022

023

1999: Internet Giants

024

025

2000s: Deterritorialization

026

027

2005: Co-working

028

The Office

Critical Analysis

029

030

Taylorism

Frank Lloyd Wright / 1900s

Taylorism, or scientific management, was theory

of work management delineated by Fredrick

Winslow Taylor and highly influential in the early

era of the office. Born out of the manufacturing

industry, the rationalization of the workplace

under the auspices of productivity resulted in a

specific arrangement of workers to be monitored

by managers from peripheral locations. Frank

Lloyd Wright’s Larkin Building demonstrates this

type of model with the two large bays on either

side of the atrium, allowing long linear rows of

employee’s desks to be viewed strategically from

either end.

Larkin Building / 1904

031

032

Corporate America

SOM / 1950s

The post-World War II office saw the introduction

of modular furniture and partition systems

into the workplace, an intermediary step before

the introduction of the cubicle which would

personalize the panels to each employees desk.

The period of modernist architecture between

the 1950s and 60s also formed a high point

of experimentation in the development of the

prototypical office tower, with firms such as SOM

exploring various elevator core positions and

glazing systems, which would ultimately solidify

into the central core and open plan shell buildings

that dominated the latter half of the 20th century.

Chase-Manhattan Bank / 1961

033

034

Burolandschaft

Quickborner Group / 1960s

Harbingers of the open plan, the designs of

the Quickborner Group in Germany entitled

Burolandschaft signaled a departure from the

Taylorist rationalization and were built around

an alternative metaphor of landscape. Their

deceivingly random distribution of furniture,

storage units and planters were intended to

provoke greater interaction between employees

while at the same time maintaining an open

environment for managerial staff to survey their

teams. Coinciding with the boom in clerical

duties attributed to the growing complexity of

the business world the designs include a plethora

of storage utilities ranging from small filing units

to an array of large standing cabinets.

Osram Offices / 1963

035

036

The Cubicle

Robert Propst / 1968

The brainchild of Robert Propst while working

for Herman Miller, the Action Office ushered

in the era of the cubicle, and was so successful

more recent iterations are still being sold today.

Released originally in 1965 to a disappointing

reception, Propst revised the system and upon its

re-release in 1968 with a ‘II’ appended to the title

its sales skyrocketed, cementing Propst’s legacy,

for better or worse, as the father of the cubicle.

After the introduction of the Action Office II,

the movement to partitioned cells accelerated,

and combined with the rise of call centers

and software development, quickly became a

standard element of the workplace. An infinite

variety of panel sizes, shapes, heights and colors

populated office merchant’s catalogs, and further

internalized the design of the office, as the cubicle

became a space within a space.

Cube Farm / 1980s

037

038

Open Plan

Google Offices

A survey of a number of Google’s offices around

the world show that they typically choose linear

buildings that enable the interior street to develop

axially, with smaller crossings at regular intervals.

All but one of the examples below exhibit looped

circulation, with parallel routes connected at

the ends, and public meeting spaces distributed

along the corridors. The other important element

in their design is the use of larger, destination

spaces at the ends of the streets, inviting employees to traverse the entire length of the building

which increases interaction possibilities.

Google Moscow

Google Stockholm

Google Zurich

2010

28,000 f2

2009

9,870 f2

2008

129,160 f2

039

Googleplex (Bldg 43)

Google New York

2005

180,000 f2

2010

2,900,000 f2

040

Organization Types

1900s - Present

Synthesizing the last one hundred years of office designs, four distinct organizational types

emerge: each a product of specific techno-social,

economic and architectural atmospheres. The

role of technology in facilitating the transformation between eras is underscored, and the current

trajectory of the office argued in this thesis posits an accelerated decentralization of the ‘workplace,’ both in ideology and materiality.

Supervisor

Employees

Amenities

Communication

Taylorism

Burolandschaft

1900s

1960s

041

Open Office

Distributed Office

2000s

2020s

042

Personal Space

Timeline

The size of the office has varied significantly

over the past 110 years, modulated greatly by the

mass adoption of technologies such as the adding

machine, typewriter and personal computer. The

physical implications of paper storage is apparent in the explosion of filing cabinets, bins and

shelving during the middle part of the 20th century, which were gradually replaced by the digital

apparatus of the our current state.

1900

1950

1960

20 ft2

30 ft2

80 ft2

043

1970

1985

2000

25 ft2

65 ft2

90 ft2

044

Demographics

2015

An aging baby boomer demographic is opening

the workforce to an ever larger proportion of

millennials, who by 2015 are predicted to make

up over 40% of the U.S. labor market, and signals

a potentially significant change in ideological

preferences and motivations.

100

Traditionalists

(b. before 1946)

80

60

Age

40

20

Baby Boomers

Gen X

(b. 1946 - 1964)

(b. 1965 - 1976)

0

% Mobile

US Workforce

0%

Workplace

20%

40%

045

Gen Y

(b. after 1997)

Millennials

(b. 1977 - 1997)

60%

80%

100%

046

Technology

Storage

Driving the expansion and contraction of the office over the past 100 years is the inherent scaling of storage needs. As the bureaucratic machine grew, more and more space was needed

to compartmentalize and store documents, files,

folders. Filing cabinets, desk drawers, desktop

organizers became standard equipment for the

average employee. The introduction of digital storage with the desktop computer heralded

the opposite trajectory, while the interface had

grown the need for physical storage shrunk. The

Internet brought a further reduction in spatial

necessity with cloud storage, enabling information to be stored and accessed anywhere regardless of the interface, private or public. These new

systems, in conjunction with ideological and demographic changes in the workforce have enabled the next generation to work everywhere,

dismantling the infrastructure that was previously necessary to operate an office and distilling the

office itself into simply a social or collaborative

atmosphere.

Desk Storage

Filing Cabinet

1850s

1950s

047

Desktop HDD

Laptop HDD

The Cloud

1990s

2000s

2010+

048

Sharing Economies

Benefits of Scale

A further extension of the technological advancement over the recent decades, the sharing

economy developed a number of innovative approaches to decentralized services, re-imagining

what conventionally would be considered owned

items. The platforms for car, bike and room shraing enable the use of underutilized resources,

while at the same time offering a greater set of

opportunities to those who might have been limited before by income or location.

Bike Sharing

Car Sharing

Hubway / CityBike

ZipCar / Rentals

049

Home Sharing

AirBnB / Short Term Rentals

050

Office / Hotel

Productive Overlap

The sharing innovations in other sectors have yet

to paralleled on a n architectural level, however,

the original shared spatial example is the hotel.

This thesis begins with the exploitation of both

the vast amount of amenity space both types

currently exhibit, and the interlocking use times:

the hotel is heavily occupied from 5pm - 11 am,

while the office is typically used during the hours

of 9 am until 6pm.

Hotel Amenities

A protoypical Hyatt hotel: 30%

of total building area is dedicated

to amenities and lobby, forming

the lower plinth.

051

Office Amenities

Google’s HQ: 25 - 30% of total

floor area on average is dedicated

to shared amenities, meeting

rooms, cafes and lecture halls.

052

WorkHotel

A Typological Experiment

053

054

Design Concepts

Vertical Organization

The design begins by re-organizing the conventional hotel, re-distributing the amenities normally occupying the hotel’s base levels throughout the tower to create smaller localized zones.

A central atrium vertically links the amenity

platforms or staging grounds for informal workleisure activities with the partitioned levels above,

providing a visual que and open circulatory system to navigate the interior.

Hotel Rooms

Lobby & Amenities

Typical Program Distribution

Re-distribution of Programs

Public & Private Zones

Localized Amenities

055

Resizing for Services

Global Connection

Figure - Void

Amenity Support Spaces

Atrium Linking Amenities

with Rooms

Private - Public Spaces

056

Urban Plan

Prudential Center

The project is sited above an existing urban mall;

a complex consisting of shopping concourses,

hotels, condominiums, a convention center and

above and below ground parking garages. Intervening in such a densely developed area offers

multiple benefits, including an already captive

audience for short term business stays with the

existing convention center. Introducing a productive space within the consumptive arcades

potentially stimulates the already prevalent shopping and dining facilities, establishing the urban

mall as the lobby for the WorkHotel. Tapping into

the concourse, the project draws on the enclosed

connective tissue that extends between parking

garage, subway station, train station and street,

and continues this urban arcade vertically within

the building itself.

N

057

058

059

060

Section

Transverse

Developed predominantly in section, every group

of room types form a perimeter above an entry

level and atrium which facilitate the visual and

circulatory access from below. While every level

is tailored to a different type of working methodology, each grouping of floors functions similarly

as a vertical transition between a public lobby

and gradually more private enclosed spaces.

061

Restaurant

Loft Suites

Bar

Executive

Suites

Gym

Doubles

Black Box

Theater

Standards

Cafe

Capsules

Pool

062

Axonometric

Circulation

The buildings circulatory system is comprised of

a vertical core at the rear and localized circulation

paths on every group of levels. As the programs

of each vertical segment are different, so too the

circulation changes, at times forming a perimeter

around the central atrium, cutting across the void

or alternating between interior and facade.

(064 - 068) The following pages depict three of

the amenity levels: the lobby, the cafe and the bar.

063

064

065

066

067

068

069

070

Levels

Axons & Plans

Each group of levels is tailored to a specific set

of criteria. The lowest levels are dedicated to

capsule style rooms, providing small, individual

sleeping spaces at night and transforming during the day into team desks. The second group

consists of standard rooms, with multiple modes

of entry to provide longer term living spaces

while enabling short term occupancy during the

daytime for business meetings and group work.

Executive suites form the third group, organized

around the executives office, with a front room

that can be used for secretarial purposes or as a

waiting room - the futon doubling as seating and

bed. The top level is dedicated to the loft style

rooms, each of which are accessible from a lower,

public entry, and from an upper, private entry.

The most costly, these rooms offer visual discretion and the most privacy.

071

Loft Suites

Executive Suites

Doubles

Standards

Capsules

072

073

Presentation jacuzzi

Futon sofa

Louvered wall

Executive Suite

Business by day, leisure by night.

The suite features a louvered

divider separating the enormous

bathtub from the sleeping area.

074

075

Bathroom stair

Upper entry

Lower entry

Loft Suite

Generously sized, the loft offers

dual means of entry, a public and

a private, useful for clandestine

meetings or unnoticed exits.

076

077

Fold down

tables

Slide up beds

Roll up bedding

Garage door

openings

Capsules

A set of basic mechanical systems

enable the capsules to sleep four

individuals, or provide a shared

workspace for a team of 4-6.

078

079

Murphy bed

to desk

Bathroom acts

as a locker

Dual entry through

room or bath

Two way

storage closet

Standard Room

Using the bathroom as a locker,

the room transforms daily from a

sleeping unit to a meeting space.

080

The End

081

082

Appendix A

Thesis Defense

083

084

Thesis Defense

19 December, 2013

085

086

087

088

Appendix B

Model Photos

089

090

Model Photos

Prudential Center

091

092

093

094

Appendix C

Alternate Experiments

095

096

Wall Sequencing

2013-11-09

A previous proposal to re-sequence the typical

office day within a single building using a system

of architecturally differentiated walls to delineate

the various spaces used throughout a workday.

Linearly juxtaposing the various types of spaces

creates two distinct grains, with an axis along

each wall and one crossing back and forth over

every wall.

Pattern Plan

097

Meetings

Group Tasks

Individual Tasks

Entertainment

Socializing

Exercise

Informal meetings

Typical Spatial Sequence

098

Fully Enclosed

Social Active

Semi-Enclosed

Social Passive

Social Active

Open Plan

Social Passive

099

Bar

Wall

Meeting

Wall

Screen Light Group

Wall Wall Wall

Re-sequencing of spaces

Exercise

Wall

Lounge

Wall

100

Bar / Meeting

Process Work

Presentation

Group Process

101

Circulation

Void

Team Space

Informal Seats

Exercise / Sauna

Coffee / Lobby

102

Wall Shifting

2013-10-19

This proposal suggested creating specific, operable walls for each of the four distinct types of

work spaces: individual tasks, group work, meetings and social areas. Spaces that require enclosure are placed within the moving walls, while

those that benefit from open areas are placed in

the floor, and are revealed and changed as the

walls above are reconfigured.

Resizing the conventional cubicle

103

Conference Room: Social Dimensions

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

Bibliography

List of Illustrations

115

116

Bibliography

Abalos, Iñaki. Tower and office : from modernist theory to contemporary practice. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003.

Benjamin, Walter. The Arcades Project. Ed. Rolf Tiedemann. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002.

Citrix. “Workplace of the Future: A Global Market Research

Report.” citrix.com. September 2012. 7 July 2013. (http://www.

citrix.com/content/dam/citrix/en_us/documents/solutions/MobileWorkstyles-Survey.pdf)

DEGW. “DEGW Report: The Impact of Change.” aecom.com.

2007. 9 August 2013. (http://www.europlan.co.nz/documents/

DEGW%20Report%20on%20Workplace%20Change.pdf)

Deleuze, Gilles & Guattari, Felix. Anti-Oedipus. Trans. Robert

Hurley. London: Continuum, 2004. Print

Esselte Corporation. “The Future of Work.” esselte.com. 2013.

13 July 2013. (http://www.esselte.com/img/compel/Ijq33xvdsEXxrehMmWjt7FFF1IJ40dQc.pdf)

Intel Labs. “The Future of Knowledge Work.” intel.com. October

2012. 14 July 2013. (http://blogs.intel.com/intellabs/files/2012/11/

Intel-White-Paper-The-Future-of-Knowledge-Work4.pdf)

Intuit. “Intuit 2020 Report: 20 Trends That Will Shape the Next

Decade.” intuit.com. October 2010. 7 July 2013. (http://httpdownload.intuit.com/http.intuit/CMO/intuit/futureofsmallbusiness/intuit_2020_report.pdf)

Koolhaas, Rem. Delirious New York: A Retroactive Manifesto for

Manhattan. New York, NY: The Monacelli Press, 1994. Print.

Latour, Bruno. We Have Never Been Modern. Cambridge, MA:

Harvard University Press, 1993. Print.

117

Martin, Reinhold. The Organizational Complex: Architecture, Media, and Corporate Space. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2003.

Print.

Martin, Reinhold. “The Organizational Complex: Cybernetics,

Space, Discourse.” Assemblage, no. 37. December 1998. 102 127.

Myerson, Jeremy. Radical office design. New York : Abbeville Press,

2006.

MIT Research Laboratory of Electronics (RLE). “A Last, Loving Look at an MIT Landmark -- Building 20.” Undercurrents,

vol. 9, no. 2. Fall 1997.

Taylor, Frederick W. The Principles of Scientific Management. New

York: Norton, 1967. Page 2.

Tschumi, Bernard. Architecture and Disjunction. Cambridge, MA:

The MIT Press, 1996.

Yeang, Ken. Reinventing the skyscraper : a vertical theory of urban

design. Chichester: Wiley-Academy, 2002.

118

List of Illustrations

Larkin building atrium. Photograph. n.d.. Roll on - a short history of the swivel chair. Bene Office Furniture. Web. 09 Aug.

2013.

page 012, center

“Office Next to Light Court, Larkin Building, Buffalo.” Photograph. 1930. Vintage Office Photographs. Office Museum. Web.

09 Aug. 2013.

page 012, background

Chase-Manhattan Bank. Photograph. n.d.. 1950s Corporate

America. Caruso St John Architects. Web. 17 Jul. 2013.

page 014, center

“Executive floor, Chase Manhattan Bank.” Photograph. n.d..

1950s Corporate America. Caruso St John Architects. Web. 17

Jul. 2013.

page 014, background

Quickborner Team. “Test Room for the Bertelsmann Group.”

1960 / 61. Symposium Burolandschaft. Arch +. Web. 18 Jul.

2013.

page 016, center

“Osram Offices, Munich, Walter Henn.” Photograph. n.d.. Burolandschaft. Caruso St John Architects. Web. 17 Jul. 2013.

page 016, background

Herman Miller. Action Office II. Photograph. n.d.. Design Icon:

The Cubicle. Design Bureau. Web. 18 Jul. 2013.

page 018, center

Herman Miller. Action Office II. Photograph. n.d.. An Idea

Whose Time Has Come. Metropolis Magazine. Web. 18 Jul.

2013.

page 018, background

Tron. Dir. Steven Lisberger. Walt Disney Productions, 1982.

Film.

page 020, center

Playtime. Dir. Jacques Tati. Jolly Film, Specta Films, 1967. Film.

page 020, background

Jean Tessier. Google Workstation. Photograph. n.d.. Jean Tessier @

Google. Jean Tessier. Web. 12 Jan. 2014.

page 022, center

Google meeting area. Photograph. n.d.. Google’s New Office in

Dublin. Home Designing. Web. 09 Sep. 2013.

page 022, background

119

Man on cell phone in airport. Photograph. n.d.. United: wifi

Internet & streaming video for Aussie Boeing 747s. Australian

Business Traveler. Web. 17 Jul. 2013.

page 024, center

Man studying in Starbucks. Photograph. n.d.. The Starbucks Student. Lily in Canada. Web. 09 Jan. 2014.

page 024, background

New Work City co-working space. Photograph. n.d.. Have A

Look at the Space! New Work City. Web. 17 Jul. 2013.

page 026, center

New Work City co-working desks. Photograph, n.d.. New Work

City Member Show & Tell! Meetup. Web. 17 Jul. 2013.

page 026, background