C reative Commons (CC) licenses

advertisement

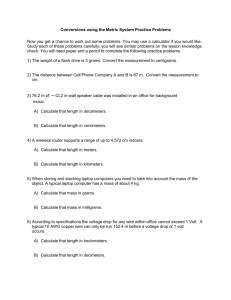

AALLSpectrum_Apr:1 3/16/10 1:51 PM Page 20 f r e e i n g c r e a t Understanding the Creative Commons licenses By Steven J. Melamut C reative Commons (CC) licenses offer authors increased potential for broad distribution. Simple terms and instant authorization make these licenses very attractive to users and providers alike. U.S. copyright law inhibits use, whereas CC licenses promote wide dissemination of materials. What are CC licenses and how do they differ from copyright? 20 AALL Spectrum ■ April 2010 When Copyright Doesn’t Work As I typed the text of this article into my computer and saved it to the hard drive, it became entitled to a bundle of rights called copyright. Protection is granted automatically, regardless of my intention, and requires no intervention upon my part. Users may not copy, publish, translate, or distribute this text without permission. (There are exceptions, such as “fair use,” but ignore that for the moment.) When the copyright law was initially written, books, maps, and charts were protected for a maximum of 28 years provided that the material was registered, a copy of the work was placed in a depository, and the author was American. This means that at that time, my article would have been unprotected. Copyright law provided exclusive rights to printing, reprinting, or publishing a work. Copyright law now protects most creative works automatically when they are placed in a tangible form— registration, deposit, and notice are no longer required. Congress has increased the length of the copyright term 11 times in the past 40 years. Today, works are protected until 70 years after the creator’s death—and perhaps longer if Congress retroactively extends the period again. Most librarians have faced copyright questions because by nature of their work they distribute copyrighted information. Once upon a time, a law firm librarian would circulate an original publication to interested parties. The book or publication would travel from office to office. Later, as technologies changed, it became the practice to circulate copies of the original, which in turn brought both copyright concerns and litigation. Today, the wide use of e-mail and intranets leads to the distribution of digital copies, which raises even more legal questions. This is © Steven J. Melamut • image © iStockphoto.com/Lise Gagne especially true because it is not possible to use any material on a computer without creating a copy and thereby raising the specter of copyright violation. Those of us in education have all encountered questions about placing materials on the internet and course management systems, often from instructors who want to distribute the most recent and relevant materials to their classes. Frequently, we are asked to find a way to distribute articles from today’s newspaper or a recent journal article. Many schools used to assume that “fair use” covered all of these uses, but it has become clear that this is an imprudent course. The legal term “fair use” is not the same as most people’s idea of fair use and is usually defined in a court of law. As a result, most schools have policies defining what they consider fair use and ultimately what level of risk they are willing to assume. Some schools seek and pay for permissions on all materials used in course-management application in an effort to avoid this question. Seeking traditional permissions under copyright law can be incredibly frustrating. The costs of licenses are frequently out of proportion to their apparent value. In many cases it is not possible to identify or locate the rights owner, and, in some cases, the rights owners no longer exist. Furthermore, determining whether material has entered the public domain and may be AALLSpectrum_Apr:1 3/16/10 1:52 PM Page 21 e a t i v i t y AALL Spectrum ■ April 2010 21 AALLSpectrum_Apr:1 3/17/10 1:26 PM Page 22 used without permission has become complex as a result of the periodic revision of the statutes. Obtaining copyright permissions is a time consuming endeavor under the best of circumstances since most publishers only grant written permission and may not accept e-mail or rush requests. Many materials do not get used or distributed simply because it is too much of a hassle or the transaction costs are prohibitive. Enter the Creative Commons and scientific works. CC licenses apply in addition to copyright and do not seek to replace copyright. It is important to note that nothing in the CC licenses affects “fair use.” CC does not modify, clarify, or in any way affect those existing rights under the copyright law. Digital technology and the internet have promoted increased creativity including many derivative works. Many artists create “mashups” of audio or video files. Visual artists may digitally alter a photograph or picture to create a new derivative work. Others combine numerous digital files into a single new work. CC licenses help create a pool of resources that can be freely used for these purposes. The CC license even adds a requirement for attribution that is not required under the copyright law, meaning that the creator will always receive credit for his or her work. Creative Commons (CC) began in the basement of Stanford Law School in 2001 and was created to restore copyright to the nation’s founders’ original intent: to promote innovation and creativity. Many creators want their works to be freely distributed. Many people feel that the current copyright climate inhibits rather than promotes creativity. Appending a The CC Licenses copyright statement There are two uses that and a © to a are controlled by CC work defines that licenses and three “all rights are restrictions. reserved.” These combine Omitting the to create six Digital technology copyright different and the internet statement licenses and a and symbol, simple regimen have promoted however, does that can be increased creativity understood by lawyers and including many non-lawyers derivative works. alike. The two uses are the freedom to share and the freedom to remix. The freedom to share permits users to reprint materials, place them on a website, publish them, etc. The freedom to remix involves combining works to create a new derivative work. The rights holder can permit either or both of these freedoms. It is possible to limit these freedoms in three easy ways. The creator may prohibit commercial use, prohibit derivatives, or permit derivatives but require that they have the same CC license as the original materials. The CC website http://creative commons.org/about/licenses describes not the six licenses thusly: change that • Attribution: This license lets status under current law. others distribute, remix, tweak, Unlike the copyright statement, a and build upon your work, even CC license symbol states only the rights commercially, as long as they reserved by the creator and thus releases credit you for the original all other rights to the user. It enables creation. This is the most immediate use of the material without having to consult the creator. It does not accommodating of licenses prevent the reserved uses—they simply offered, in terms of what others require permission. The idea is to can do with your works licensed promote the use of cultural, educational, under Attribution. 22 AALL Spectrum ■ April 2010 • Attribution Share Alike: This license lets others remix, tweak, and build upon your work, even for commercial reasons, as long as they credit you and license their new creations under the identical terms. This license is often compared to open source software licenses. All new works based on yours will carry the same license, so any derivatives will also allow commercial use. • Attribution No Derivatives: This license allows for redistribution, commercial and non-commercial, as long as it is passed along unchanged and in whole with credit to you. • Attribution Non-Commercial: This license lets others remix, tweak, and build upon your work non-commercially, and, although their new works must also acknowledge you and be noncommercial, they don’t have to license their derivative works on the same terms. • Attribution Non-Commercial Share Alike: This license lets others remix, tweak, and build upon your work noncommercially, as long as they credit you and license their new creations under the identical terms. Others can download and redistribute your work just like under the Attribution NonCommercial No Derivatives license, but they can also translate, make remixes, and produce new creations based on your work. All new work based on yours will carry the same license, so any derivatives will also be noncommercial in nature. • Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives: This license is the most restrictive of the six main licenses allowing redistribution. This license is often called the “free advertising” license because it allows others to download your works and share them with others as long as they mention you and link back to you, but they can’t change them in any way or use them commercially. Two additional tools are available on the CC website: CC0 and Public Domain Certification. CC0 permits you to waive all interests in your work. It effectively places the material in the public domain as if the copyright period had expired. The Public Domain Certification tool is used to certify that a work has already entered the public domain. This tool may not be valid outside of the United States. (For more information, see http://creative commons.org/publicdomain.) AALLSpectrum_Apr:1 3/17/10 1:27 PM Page 23 Materials must be registered on the Creative Commons website and three formats of the chosen license are created. All of the licenses clearly state attribution and provide a means of contacting the author. The first format is a “Commons Deed,” which explains the license in ordinary English (described by CC as “human readable”). The second format is “Legal Code,” which is intended to be read by lawyers. Lastly, a machinereadable “Resource Description Framework” metadata describes the key license terms. This machine code is accessible by many search engines such as Google and Yahoo. It is possible to search only for materials with CC licenses using these search tools. The results of the searches can then be used immediately without fear. Some sites, like the photo sharing site, www.flickr.com, include a CC license option in their file upload procedure and their site search engine. Participating search engines are listed at http://search.creativecommons.org. CC licenses have been adopted by many artists, musicians, filmmakers, and educators. Wikipedia; Google Books; the Public Library of Science (PLos); and Oyez, the U.S. Supreme Court media website, all use CC licenses. The Massachusetts Institute of Technology OpenCourseWare website provides open access to the university’s course materials published under the CC Attribution Non-Commercial Share Alike license. There are even add-in tools available for Microsoft Office and Open Office to facilitate adding these licenses. To use CC licenses, you much first choose the license at http://creative commons.org/choose. The website will generate a url for the license and provide graphical icons if you choose to use them. The licenses are non-revocable, meaning you can remove the license from the material but you cannot take back permission from those who have already used or downloaded the materials. The license is also perpetual— it is not possible to restrict the time span of the license—and non-exclusive, meaning it is still possible to submit the work for publication or sell the right to include it in a commercial work. Since the CC license is irrevocable and nonexclusive, it is not possible to grant an exclusive license at a later date. Please consider using CC licenses for your work. It is an easy way to tell people that they can share, use, and build upon it. These licenses are the ideal vehicle for individuals who want their materials to be widely seen and used. Also, be sure to keep alert for the CC symbols on works you see on the internet, as they are intended to be shared and used. ■ Steven J. Melamut (melamut@ email.und.edu) is information technology services librarian at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Law Library. 'R\RXKDYHD EULJKWLGHD" $SSO\IRUDQ$$//%1$&RQWLQXLQJ(GXFDWLRQ*UDQW • The AALL/BNA Continuing Education Grants Program helps fund educational programming outside of the Annual Meeting. Educational programming that can be distributed to the entire AALL membership will be given priority. • Chapters, special interest sections, member institutions, and individual AALL members are eligible. • Guidelines for proposals and the application form are available online at www.aallnet.org/prodev/grant_program.asp. • The deadline for the fourth round of proposals is May 6, 2010. Memorials AALL Spectrum has been advised of the deaths of Stanley Keith Pearce and Marjorie C. Wilcox. Mr. Pearce graduated from the University of Washington with a BA in psychology in 1950, a JD in 1956, and a master’s degree in law librarianship in 1957. He was employed at the Los Angeles County Law Library until he joined the law firm of O’Melveny and Myers in Los Angeles in 1959, where he remained until his retirement in January 1986. Mr. Pearce served as president of the Southern California Association of Law Libraries from 1968-1969 and as a member of the AALL Executive Board from 1977-1980. He died on February 2. Ms. Wilcox attended school in Fort Wayne, Indiana, before moving to Grand Rapids, Michigan. She was an active member of her church and worked to provide services to the blind. In 1968, Wilcox became executive director and law librarian for the Grand Rapids Bar Association, where she remained until her retirement in 1988. In addition to receiving the Liberty Bell Award from the bar association, Wilcox served as the first president of the Michigan Association of Law Libraries. She died on February 5. AALL Spectrum carries brief announcements of members’ deaths in the “Memorials” column. Traditional memorials should be submitted to Janet Sinder, Law Library Journal, University of Maryland At Baltimore, Thurgood Marshall Law Library, 501 W. Fayette Street, Baltimore, MD 21201-1768; jsinder@law.umaryland.edu. AALL Spectrum ■ April 2010 23