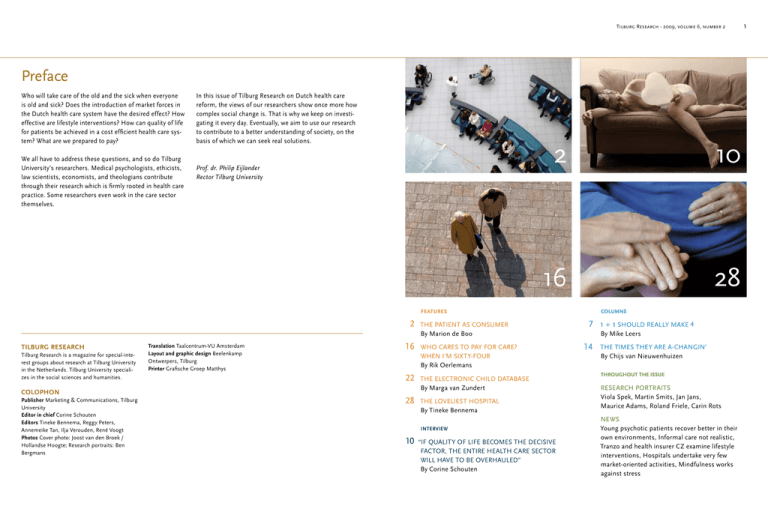

Preface

advertisement