by

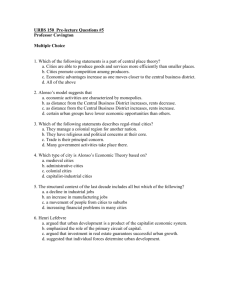

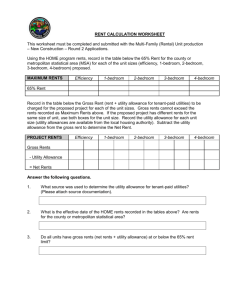

advertisement

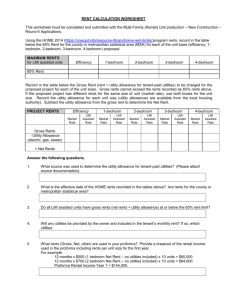

THE DETERMINANTS OF OFFICE LOCATION IN THE NEW YORK METROPOLITAN REGION by James Murphy B.A. Yale University 1980 Submitted in Partial of to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning of the Requirements for the Degree Fulfillment Master of City Planning at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology June 1983 James Murphy 1983 grants to M.I.T. permission to reproduce document in whole thesis copies of this The author hereby and to distribute or in part. Signature of Author D r-tment of Ur a tudies and Planning NJ 9 May 1983 Certified by Professor Karen Polenske Thesis Supervisor Accepted by I iz Hotc MASSACHUSETTS iNSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUL 211983 LBRARIES Professor Donald Schon Chair, MCP Committee The Determinants of Office Location in the New York Metropolitan Region by James Murphy Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning on 9 May 1983 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Degree of Master of City Planning. Abstract In New York City, as in the nation, blue-collar employment is losing ground to white-collar, factories to offices. Since office jobs are concentrated in Manhattan, there is a growing disparity of employment opportunity between Manhattan and the outer boroughs of New York City. Moreover, this spatial disparity is compounded by an immense skill disparity: office jobs are ill-suited to New York's huge blue-collar labor force. The continuing loss of manufacturing jobs, nonetheless, has caused many to look to office development as the only potential source of new jobs in the outer boroughs. These outer boroughs are thought to be in competition with the suburbs primarily for back office functions that are priced out of the Manhattan office market. We designed an empirical analysis of the determinants of office location in the suburbs of New York City. Such a of the us judge the ability study, we thought, could help We sought to office development. outer boroughs to attract explain the variations in office rents across towns by cost Do rents vary across factors, and by amenity factors. towns because the costs of office development vary, or because the amenities of the towns vary? We hypothesized that since the supply of office space is fixed in the short run, demand for various amenities would bid up rents in some towns more than others. The results of our analysis were consistent with our hypothesis: amenity factors predicted rents much better than did cost factors. We suggest that long-term rent differentials across towns can best be explained if one assumes a monopolistically competitive office market. We interpret our findings in the context of other important theoretical and empirical research on office location. 2 What consequence do these findings have for New York development in the outer to stimulate office City's efforts The amenity orientation of office location poses boroughs? dilemmas for the city in that those locations most attractive to developers are also those locations least in only by we argue that Finally, need of development. reducing the fiscal and political balkanization of the development office New York be able to divert region will from Manhattan to the depressed business districts of the outer boroughs. Thesis Supervisor: Professor Title: Karen Polenske 3 Acknowledgments I and am indebted This Economics. during I committee: and Karen when at times William C. Wheaton, that was there who provided underpinnings theoretical Polenske, confidence her thesis, for for RPA research my members the thank Professor encouragement President 1982. to wish also of study grew out the summer of Vice Armstrong, Regina to particular in (RPA) Plan Association to the Regional my of for my advisor, Professor doubt; and Mr. of the study; on help essential her complete my I would some thesis the Edward H. Kaplan, for his indispensible help in designing the statistical analysis. Ed Kaplan merits special acknowledgment because of his brilliance, patience, and generosity. to my parents, I am very grateful Murphy, for their support constant Finally, but by no means typist, Ms. Jacqueline LeBlanc, processor proved indispensible. 4 least, whose Mr. and I am skill and Mrs. Donald encouragement. indebted with the to my word Scheme of Contents Page 6 Its Consequences........ ........ I. The Transition and II. Back-Office Development: Fact or Mirage?..........10 III.The Outer Boroughs Versus the Suburbs..............13 IV. An Analysis of the Determinants of Office Location........................ ......... A. B. C. D. V. The Cost Model... The Amenity Model ............... . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .16 .18 .23 .26 Office Location. ........ 31 Specifics of the Cost Model........... . Amenities and Monopolistic Competition . Amenities and Office Location Theory.. . Offices and Household Location Theory. . Public Policy and Office A. B. C. . . 00 0 . . Diagnostics.... ...... 0 The Amenity Orientation of A. B. C. D. VI. Introduction..... The Variables and Some 16 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .32 .33 .35 .37 Location...................39 A Role for Government?................ The Dilemmas of Office Development.... What Is To Be Done?................... . . . . . . . .39 . . . . .41 . . . . .45 Tables.................................................48 Table 1: Data Matrix for Selected Variables.......48 Table 2a: 1982 Electricity Cost Differentials Table in the Reg ion ............................ 1981 Income Tax Differentials in the Region............................51 2b: 51 Table 3: 1980 Office Building Operating Table Expenditures.............................52 Correlation Matrix for Selected 4: Variables................................53 Table 5: Derivation of Dependent Variable and Its Variance.........................54 Notes..................................................55 Bibliography...........................................58 5 I. The Transition and Its Consequences The office building has come to replace the factory as the symyol of contemporary urban economic development. New York 1950-1980, City's economic the manufacturing city lost problems 540,000, Of the jobs. 1977, 227,000 were remain or 558,000 severe. one-half, of net job loss in manufacturing. From its from 1970- By contrast, there was a net gain of 111,000 jobs from 1977-1980, despite a loss of 40,000 This fledgling recovery, during the early in business jobs. after during this period. 2 loss of jobs a catastrophic 1970s, was due almost entirely and professional Since jobs manufacturing 1977, services the growth -- of to growth that office is, office employment has exceeded the decline in manufacturing employment. important More the profound growing to of office this disparity net employment gain is of the New York economy from transformation manufacturing consequence than the simple employment. long-term of One structural employment important change opportunity is a between Manhattan and the four outer boroughs of Staten Island, the Bronx, Brooklyn, the service, in was and Queens. Because dominates finance, insurance, and real estate industries New York City, limited the partial job recovery from 1977-1980 to Manhattan. 1.0 percent in the rest of the city. Brooklyn period and 6 in sector during of this Private 6.5 percent boroughs Manhattan the employment rose Manhattan, Worse, Bronx, but less than in the poorest private sector employment are Since manufacturing jobs jobs, the long-term substitution are office than of office for economic the worsen to tend will employment manufacturing city the throughout distributed evenly much more 3 declined. actually disparity between Manhattan and the outer boroughs. are by no means unique These trends the rather, to an increase in in II, is due grew from economy workers, to Employment in to 57.1 30.4 million and finance, trade, of and government. sector tertiary a Since World War service industries of manifestation the American in and tertiary the dramatic white-collar transportation, services, the a of the growth all virtually but transformation. economic national growth is city to New York City; million jobs over the period 1950-1975, or from 54 percent to 69 percent The of the nation's national employment has transition The centripedal location contrast from -- favorably With cities to suburbs, manufacturing to service the from the point of of view of that characterize forces flight office characterize that forces with the centrifugal manufacturing. 4 consequences for the economy of significant cities. cities -- workforce. manufacturing and from the Northeast to the from Southwest, many geographers and city officials believe that office development promises center cities. offices is patterns. base for declining The concentration and employment density of thought This a new economic to be ideally suited to urban land-use is not to say that there has been little 7 in pronounced 5 cities. Australian Office migration to markets, downtowns between own: percent of in major and by 1975.6 major downtowns net addition acquired a constant share of they have retained overall to reason some thus tertiary sector will that expect 22 space, of office There 23 percent of total national detached office space.7 is the percent of cities seem to have held their 1975, the nationwide that meaning 1960 in dramatic growth of suburban office even with the Still, is 313 firms, or to 63 percent, and declined suburbs 500 Corporation at 71 1963 in peaked areas metropolitan or firms headquartered The number of these headquarters. is more in British the of Fortune the case in dramatic especially than States, United the like offices, has been extensive and in general, suburbanization total suburbanization of of offices; dispersal the of growth the strengthen the economic base of major cities. It be would misleading, however, simply if aggregate employment measures and conclude that, employment well. As growing due is we saw in during 1977-1980, the net important in disparities: Brooklyn work: equivalent the New of York's declined, manufacturing a gain city, of one New York 8 is all "recovery" was able example, to at is by no means job. office for asymmetry is A fundamental loss of one manufacturing job to overall increase in employment masked employment and the Bronx. survey development, to office case the to As a provide major many to jobs middle-income either highly-paid (and are typically workers. male 8 this structural the enter labor window on New York's 1970, the The consequences of employment. service of the exceeded the unemployment 1970, while after below consistently was rate unemployment before that economy may be the fact this of consequences employment consistently has to the are not suited hope without force average, the national is mismatch can only worsen as low-income men to a service transition proportions immense of the low-income workforce. skills rate of mismatch A because the jobs created developing One for the enormous number of blue-collar employment potential does not offer sector the service of income, distribution to produce a more unequal Besides tending by women). or jobs for experienced professionals, poorly-paid jobs for clerical personnel held Now, New York are in the jobs available economy, as a service people. working-class unskilled average. national The 8.6 percent 1980 jobless rate for New York was one-fifth higher in rate 1980 in was percent. 17.7 9 statisticians have dubbed New York "the capital study conducted Development estimated on that employment Some youth unemployment Another window on the employment of the nation." to consequences of the transition a while the New York City was 28.3 percent, average national teenage unemployment the than the national average; by the City patterns commuting perhaps 75 9 a service economy Office to percent of New the of York. is from Economic It was 135,000 office women. middle-aged suited to not be 1 0 Although the employment for reducing new housewives.' suburban may jobs service 1 Such to be) do not bode well is what they prove that these chiefly blue-collar New York City residents, they to are well-suited by commuters, held 1977 are since created jobs either for New Yorkers, working-class prospects of (if trends or disparities in income. regional Reality or Mirage? II. Back-Office Development: New York City officials view the transformation of the national economy and given. These officials, along with many economists and most from the growth of recent development 1 2 sector? the service A in the Manhattan office market poses The issues for the economy of New York City. vexing policy 1980-1982 were the boom phase of the characteristic years boom-bust square from 1980-1985. Five million proportion of uneconomic for These office support costs, support it services services, ft becomes to as a increasingly pay headquarter or back-office include computer services and data processing, 10 through and higher to increase continue in Consequently, per sq. to $40 As rents operating strong remained were very low. rents rose dramatically in Midtown Manhattan. prices. Demand vacancy rates so that office 1 3 construction. of office cycle feet per year were scheduled for construction Manhattan 1982, How can New York City as: the issue define geographers, benefit its dramatic New York manifestation as functions, training programs, accounting and billing, and insurance companies have found that banks and Several can split headquarter and then areas. relocate Should city of New in York officials a trend, the suburbs, City. New to lower-rent it is of concern to office space in beyond the tax jurisdiction York City in the outer boroughs. base is the development one functions economic development hope to capture most of the relocated back-office space tax back-office since most of the low-rent the region is they functions from back-office functions this become officials check processing. hope in city's first the outer for Preventing the erosion of the concern, boroughs job growth in the is but also back-office desired stagnant as the outer borough economies. There are some functions might argued in business of at Europe importance actual back-office Robert M. of offices clients, has and to the led some face-to-face pattern of the greatest office 11 presence Since contact of offices give men whose 1 4 face-to-face dispersal the among as to to hold that accountants, and "so decisions." commonplace allow why 1926 that office activities concentrate contact arriving reasons relocate out of Manhattan. districts ease plausible then, it in urban possible is desired has concentrate in other professionals. the researchers contact. 1 5 to lawyers, The United States qualify Research communcations a order to executives, in in become among suburbs Haig to the uncover confirms the its London to higher content firms that in general, is, in the center more center-city firms have city.16 The type of job than the type of firm important a than do functions and routine of clerical remain such that indicated suburbs a telecommuni- that relocated from Central A study of firms location. require not do therefore and cations, entirely on rely almost office, functions or back- Routine, in a firm. decision-making positions the top but only for contact, face-to-face of importance in predicting dispersal. space plausible these Despite relocate out of to Manhattan, often remove incentives to may.require that require a and do conditions reflect rents the firms will consider of the office market, a not lower- short-run for incentives Given efficiency. do that not provide consistent long-run achieving efficiency relocate to location But market rent peripheral one. Long-term rents in fluctuations functions office central expect back-office to relocate. routine high-rent reasons boom-bust cycle relocating back- office functions when vacancies are low and rents high, but when rents fall, the functions disappears. small fraction associated support of total with functions incentive Since real expenses, unless there is relocate back-office estate not are only a likely to a very substantial fluctuations rent costs and since there are costs are firms moving, to send rent conflicting saving. Short-term signals to firms and may hinder the achievement-of 12 move long- in conservation and alternative investment substantial prices to signals can be extended when one considers the office market government is for role the case of energy, a sensible government. of role the alternative and conservation The analogy to sources to a standstill. In in in oil 1982 decline The firms. investmen t brought fluctuate and send energy prices sources of energy, but conflicting requires efficiency Long-term energy. of case the in is especially evident This phenomenon term efficiency. to tax energy, to maintain a high price and send consistent reduce to districts relocation of location. 1 central encouraging by would This routine office functions. the ration most need a that to those functions downtown sites scarce congestion business in central space tax office government should that argue similarly could One firms. to signals 7 III.The Outer Boroughs Versus the Suburbs New York City is need an unenviable reduce within boroughs competition space. There New to question can space office of disparity of The city. the dispersed the York the City. outer is Some degree both inevitable and desirable due to to the costs of congestion to postion. out of Manhattan of offices of dispersal due in be employment is to what captured The boroughs suburbs for opportunity extent this the outer offer stiff in low-rent is a huge prime office space market 13 the office in place in many suburban been virtually outer locations, for example, while no major office developments misleading boroughs as if no typical contrast site site. outer industrial locational advantages, it the suburbs with the The boroughs, business offer is a a typical bewildering from downtown Stamford, from Newark parks, suburbs to Scarsdale. which such as districts, vast Spring Creek such or downtown Brooklyn. whether a firm prefers The same include as to rural is true of expanses in in Brooklyn, or St. George, The issue outer There is anymore than there of locations, New Jersey, Island, to suburban diversity dense the four these were homogeneous entities. outer-borough the in have boroughs since World War II. When considering comparative is there Staten then becomes not the suburbs or the outer boroughs, but instead the specific locational characteristics desired that may be found in the suburbs, in the outer boroughs, or both. Several Development city officials, Corporation, compete with especially have argued sites. To begin with, the notion that misleading site. proposition campus-style, two that the in Public order to the suburbs, the outer boroughs must offer suburban-style office at But that even the we typical low-rise major highways, if there is some typical suburban at site the implications of 14 a view embodies provisionally office park the such suburban accept is a the large, intersection of such a popular suburban site are by no means cl ear. site that makes it attractive? What is it about Do firms want the view, or the highway? Are the buildings low-rise because the is because cheap, or firms move security? office to the The low-rise are more countrysidE simple for f act this of the land convenient? the beauty, popularity Do or for these of 1 us why they are popular. parks does not tel The debate about the r elative comparative advantages of the suburbs and exclusively on hypothesize that feature offer the couter speculati on and firms f avor a higher income anecdotes about boroughs anecdotal r esidential these plausible. theories The empirically, is whether and what such tests to of the outer suburbs for locations offices; (2) and subsidies and other office are, doubt, they can be tested us about the development location. (3) in general, to compete with to judge which specific to judge incentives No argument 15 in (1) to judge the ability what are tax the types of within a given borough are most likely development; that firm An empirical analysis may in three ways: boroughs, to no inform the debate about office the outer boroughs Others was robbed. might tell determinants of office location. be able or the president anecdotes they firm moved lives there; and question this Some because environment. r elocation: moved out of Manhattan b ecause almost evidence. suburban sites Stamford because the cha irman Many of relies to attract abatements, likely to influence is made that an empirical analysis issues can offer facing the solutions New York. distribution consequences development of may be to and vexing income, important of a site. but it the policy location of offices affects more may tell developers, The employment potential determinants site any the A study of us whether can tell than and a site is these simple locational attractive to us nothing about whether the should be developed. IV. An Analysis of the Determinants of Office Location A. Introduction Most office buildings are built on speculation by real estate developers employment is often and demand and in As one observer lead time verge 8 Profits tax partnership development supply space. on laws in in in real the This speculation of future demand, the estate United estate New York is wrote: real demand, space can States extremely cyclical be in very encourage development. in 1 9 Office character. "Inadequate information and long for construction distort and the growth in by the chronic oversupplies of office cities. 1 handsome,. equity for office based on a very sketchy analysis as evidenced many who must anticipate which is uneven 2 0 irrational." the relationship The and often office between appears market, to thus, appears to approximate the famous hog-market disequilibrium of economic theory. performance, If the office market then we would expect 16 is a boom-bust vacancy rates to fall very low during the boom and rise -- which is, vacancy 14.6 rate in fact, fell to happens. 0.5 percent In in Manhattan, 1967-68, but the rose to 1972.21 in percent what very high during the bust One reason for this cyclical pattern is the long lag between the conception of a project and its completion. The two to three-year lead time for a project means that the supply of office changes in demand. completed, use if it space cannot Moreover, immediately respond once an office is cannot be quickly converted to an alternative demand falls. What do immediately changes in demand are the vacancy rate and demand, assuming a fixed supply in vacancy rates rents, building to to fall then, and rents will tend to respond the the short term, to be bid up. be rent. determined to High causes Short-term by demand characteristics, since supply is fixed. We began our analysis by selecting the 47 towns that account for most of the suburban New York office space market and available. for which Since office with the suburbs, and market not comparable, suburban office market. and total the buildings. suburban New York. comprehensive is since We no census Our sample, inventory 17 thought were to be the Manhattan office our study to the obtained square building are we restricted number of There by the outer boroughs competing is rents rents per feet of for office though, available, square each foot of 278 buildings in was from the most an inventory that included approximately calculated the total Since a weighted mean rents our included by with assumption rents that districts stock. footage prime One we of (see Table office 40,000 the buildings, below 10 these each town by dividing excess per this 5). space, sq. we ft. We so we excluded dollars rents below office assumption, for new, in on the age of From square in buildings lacked data buildings is buildings. rent the total interest only inferior 1800 sq. ft on the correspond to expect, such would on old, an to find such low rents only in very old office such as in Bridgeport, Connecticut, or Newark, the case. 2 2 New Jersey - which was in fact We sought to explain the variations in rent across towns by a variety differentials assuming that short term, demand factors and to the supply of office amenity we expect that relating differentials. space rents will bid up amenities. places to work and by the If supply willingness is indeed town. variations B. The in Since we are fixed in the Towns to the that are to fixed pay for in the locational short term, little effect on rents. Variables and Some The cost variables (1) cost live should have office then we would expect cost factors to have the is to vary according for amenities in a particular more desirable rents of Diagnostics included the following: Two measures of the height 18 of buildings in a given town: The mean number of stories, and the proportion of buildings in a given town with more than eight stories. The taller a building, the more costly significantly more is to construct above 8 stories per square foot, and building be it costly than is thought to building under 8 stories.23 (2) Electricity monthly electric bill costs, hours (see Table 2). included in the sample were (3) away costs decrease dol lars In (4) Effective per hundred location central business district increase, commercial assessed i ndicate in locational as district, rents property tax rates, val uation. There in is no that the in with correlation inter-jurisdictional were passed on to the tenants, taxes difference s and theory, so that positive A significantly Alternatively, tax the the rents. classical the absence of any correlation the utilities), agr eement about the incidence of the commercial could differences the from to that tax. rents in rents accordingly. theoretical property all (include reflected 150,000 The distance to Manhattan in miles as a proxy moves transport the average Since virtually gross should be for transportation costs. one by for firms using approximately kilowatt cost of electricity given with rents were taxes borne while might mean that by the landlord. 2 4 a positive correlation between the property rents may advantages mean that could raise 19 towns their with significant commercial property taxes to capture some of the tax the debate on property of those locational to not adequate to contribute Our study is advantages.25 value notes and only incidence, the issues. no measure. Labor costs, (5) but substantial, labor in differences are there The cost region. between New York City and its differs Table (see but 3), included the following: tax rates, in property Effective residential We hypothesize valuation. per hundred assessed dollars New York the among suburbs. The amenity variables (1) suburbs in probably labor of significant not probably among suburbs costs metropolitan probably not are no doubt buildings office and operating constructing of costs The labor that executives choose office locations in places where they or live either would to. like We thus a expect negative correlation with rents, since high residential property taxes are a disamenity. Commuter (2) variable categorical Manhattan is assumed (3) New York, to access rail of either yes or no. Manhattan, Rail access to to be an amenity. Location by state, Connecticut, variable Jersey. Although New and unlike corporate states. Since income taxes. income taxes, state income 20 for a categorical factors may vary by state, we hypothesize that important is personal a Personal the most income taxes, vary widely across our taxes differ many by kind of three income taxed, and not simply in degree, a categorical variable the best way to attempt to capture this effect. who make locational decisions concerned with the state rate would be a with and the right of residential class, amenity is including the proportion percentage change "white flight"); who have income; in to and their from school; A highly desirable residents income, are and (5) educational several proxies the 25 years old per capita the proportion of the the number of clerical workforce; and the of the workforce. hypothesized predominately So (to measure median proportion is work near occupation. over proportion of the location and 1970-1980 the income; number of managers and their "living who are black; residents under the poverty level; the by residents population the median family workers, live and measured high very 2). or the proportion of adults completed be We expect that managers race, of to stratification, officials prefer similar assumed (see Table kind of people." a Executives income tax, and a low tax major amenity top coroporate people personal Socio-economic (4) are is white, to be one where well-educated, high in managerial occupations. School quality, as measured by county average expenditures per assumed to regard high quality capita. schools Executives are as an amenity. Our measure of school quality, though, is very poor. The information correlation about both the 21 matrix provided bivariate important relation between independent relationships 4). dependent among The the correlations independent the and variables amenity independent between variables with variables. Although this the multiple regressions, predictors for rent pattern than rents from poor data the correlations Since our variables measures of the same factor, a high of .941; .715 capita level. income, with the include we would phenomenon. we must cost in the not The this result Perhaps the independent several different expect these to have family income have and a correlation residents who are black has a proportion To avoid redundancy, colinearity, that among for example, the proportion of correlation the factors. degree of correlation. Median median per were highly than are cost factors. on cost variables. more it suggests that amenity factors are derives important are our pattern: could disappear however, more Table and interesting possibility cannot be excluded, solely rent consistently average about (see average one were and variables the displayed correlated better variables, or in use two below the statistical poverty parlance, measures of the same On the basis of these preliminary diagnostics, we chose the most promising The mean rent sample of buildings for variables (see Table 1). each town was derived located in that town, from a and weighted by the number of square feet. Since the number of square feet differed we in each town, have varying confidence in the estimated average rents. 22 degrees of Larger samples, ceteris paribus, mean better predictions, so we need to give more weight to towns with a larger feet of office number of square space in our sample of buildings. definition of mean rent, Given our and assuming that rents per sq. ft by building have constant variance, then weighted squares is the appropriate model-building least technique (see Table 5). C. The Cost Model Our first of cost taller factors. run, and the costs of rents) would certainly incidence complex was to predict of on the basis we supply is, would expect electricity be commercial If issue. then rents We assumed that the costs of constructing buildings are gross The task reflected in the fact, tax to correlation between rents and commercial assumption, positive correlation we be would part, shifted forward gradient of classical negative correlation to the and tenants. by the predict between taxes are, run, more property taxes. inelastic short a the short borne supply is the is in property taxes could indicate that in the rents. taxes fixed From significantly in property landlord. this (since these rents no A 'and not completely at Finally, least the in rent location theory leads us to expect a between rents and the distance to Manhattan. Our first model predicts rents as an additive function of the average stories of buildings, the costs of electricity and the commercial 23 property tax rate. The estimated coefficients are: (1) = 16.384 + .459 (average stories) (4.580) (2.360) rent + .249(electricity costs) - 1.641(commercial tax) (.782) (-3.395) (The figures in parentheses coefficients are T-ratios) significantly coefficient different principal with this are made about correlation explain. electricity for the commercial what assumptions negative for from zero at difficulty coefficient We will is difficult, argue later measured is the costs the .05 model is incidence, if is level. the property tax. not The negative No matter a significantly not impossible, to that this negative relation can be understood only when we assume that being the r 2 = .259 dgf = 43 The under residential Another shortcoming of this model what property is is tax really rate. that it only explains about 26 percent of the variations in rents. Our predictive second model attempts to relations remain constant distance by adding it to our see if we if these control for first model. The estimated coefficients are: (2) rent = 16.739 + (4.517) + .461(average (2.346) .269(electricity costs) - (.828) 1.697(commercial tax) (-3.359) - .017 (distance) (-.429) dgf = 42 stories) r2 = 24 .263 Neither distance nor electricity cost coefficients are significant at commercial the .05 property tax commercial tax. Since costs and distance them level. The coefficient remains difficult for the to interpret as a the coefficients for electricity are essentially zero, we decided to drop from the model. Our third model, then, additive function of the average property tax. predicts stories rents as an and the commercial The estimated coefficients are: (3) rent 19.007 + (15.410) = - .429(average stories) (2.261) 1.405(commercial tax) (-3.738) dgf r 2 = .249 . 44 = Comparing models shows essentially Still, statistically are that all models. statistic with those of these two in significant. measuring something else. problems, commercial no way In Our for implies are that particular, they we are tax coefficient is Because of these substantial we thought it tax variable, that we could account power of the previous assume that the commercial interpretive previous even though both of our coefficients significant,this to variables of the explanatory substantively forced the r 2 and fit useful a model to omit this with variables interpret. fourth model predicts function of electricity costs, 25 rents as an additive the average stories and the distance to Manhattan. The estimated coefficients are: (4) rent = 20.889 - .423(electricity costs) (5.358) + (-1.510) .141(average stories) + .018(distance) (.738) (.403) r2 = dgf = 43 .060 Here none of the coefficients the .05 less level, and the than 1 percent. explained variations in rents is It appears that the explanatory power of the previous models and the significance of stories coefficient depended on tax. is significant at Yet the commercial the average the commercial property property tax coefficient is not interpretable and may be measuring the residential property Our cost factors tax. power. our appear to have This result does not prove, but assumption possibility that short-term remains that or that we are measuring D. these is supply results consistent with is fixed. The are due to poor data the wrong cost factors. The Amenity Model Our second task of amenity factors. the almost no explanatory variations was to predict rents With supply fixed in rents should on the basis in the short stem from shifts run, in the demand curve due to a willingness to pay for a desirable location. could What So we would expect that command higher rents than constitutes a desirable 26 more desirable less desirable location? locations locations. We assume that executives, like everyone, rather than long ones. in offices And prestigious and also they live want profile, a desirable but their like to work locate their like offices to in to to live. locate short, in other From these assumptions we would town also have trips or would fashionable places where, large firms have located. expect short So they would a town where executives prefer to have high fashionable office a a socio-economic district. We assume that it requires a certain critical mass of managers to make a town fashionable, number of managers. be thought would reduce the though the high-income such profile a clerical workforce of the town. Finally, lower residential property to higher. first model of the residential of managers, income per predicts property the number of clerical rents as tax rate, workers, capita. The estimated coefficients are: (1) for large clerical workforce might also are assumed to prefer Our function A desirable, executives taxes so we used the variable rent = 13.802 - 1.333(residential tax) (12.484) (-4.219) + 2.440(managers) (8.073) + dgf = 42 .263(clerical) (-2.673) .258(median income) (2.798) r 2 = .844 27 an additive the number and the median All different of our coefficients from zero at the .05 level, are significantly and the model expains 84 percent of the variations in rents. Since this clerical workers workforce, measuring Our model instead there the is a of their chance effects of the (.971) size workers and both (see Table colinearity, we decided if our that we are the in managers 4). groups and the just town on rents. (.755) Because of fact high correlations to control occupational proportions size of correlation matrix shows population see uses the number of managerial and of this between clerical danger of for population size and retain any independent explanatory power. Our second model, then, simply adds the population size to the first model. The estimated coefficients are: (2) rent = 13.802 (12.331) 1.333(residential tax) (-4.164) .258(median income) + .000(population) (2.757 (-.008) + + 2.439(managers) - .261(clerical) (7.772) 2 (-1.027) dgf = 41 r = .844 It the is previous population simultaneously at the .05 to exert level. remarkable just how similar this model one and -- except the become that number the of insignificantly coefficients clerical explanatory 28 for workers different The number of clerical no independent is to from zero workers appears power apart from the size of the population. appears to retain controlling The number of managers, a significant for predictive population size. however, power even after It is not, then, simply the size of a town that makes it desirable for offices, but the size of the managerial population. not prove, desire but is consistent with, Such a result does the theory that firms fashionable locations. Our third model predicts rents property as tax population, (3) rent = summarizes an additive rate, the these function median of income findings, the per and residential capita, the and the number of managers. 13.695 - 1.406(residential (12.280) (-4.503) + .289(median income) (3.272) + - tax) .018(population) (-2.431) 2.267(managers) (8.537) r 2 = .840 dgf = 42 These willingness equal, 1.41 to firms dollars residential dollar pay for are willing for one reduction 1000 increase The in interpreted 29 as a Other things rent dollar tax rate, population, be amenities. to pay in every property can certain increase in the median 1000 poses an coefficients per square foot: reduction cents income, in the for every 1000 2 cents for every and 2.27 dollars for every in managers. negative relationship interpretive question. 29 of population Why should an to rents increase in population reduce correlation rents? of rent (.120). But this positive the number managers. higher rents managers. is positive But between larger control significant large Brunswick, matrix and rents at the .05 the larger level. black Elizabeth, in our sample, perspective of income, that population Although significantly (see Table by 2). for decided to these is corporate state, include We 30 negative New York immediately think such as Newark, The New correlation has Given that all a -. 409 of population these -- negatively income taxes tax the is not to rents. taxes do that while income it related income is from disamenities, a categorical state. mean cities with a large not vary vary widely costs do for executives do. personal the and at .440 correlation personal This suggests by state, amenities test -- managers be indicates more population intuition: with does turns Bridgeport. with the proportion of blacks. correlated and metropolitan residents. and correlation with median surprising rents to This makes sense when cities cities in our confirms positively seems population to be older, declining industrial the positive for the number of managers, between population proportion of poor, of a bivariate slightly correlation relation So once we we consider that tend is the insofar as a larger population the relation and begin with, and population measuring of To not vary In an attempt to differentials, variable for we location by Our categorical fourth variables model simply to the third added the state model. The estimated coefficients are: (4) rent = 13.740 - 1.024(residential tax) (9.141) (-2.339) + + .296(median income) - .016(population) (3.572) (-2.088) 1.822(managers) + 1.830(Connecticut) (6.006) - (3.055) .722(New Jersey) - (-1.616 r 2 = .873 dgf = 40 Although categorical a category has state variables do not tell us why predictive power, categories the 1.108(New York) (-5.472) are quite importance of the coefficients of consistent personal these with our theory income taxes on of location amenity. Connecticut rents, and is the only state of the three that does not tax earned tax income; and has Jersey's New York effects, levies is related thus, strong effect between is models significant are positive effect the most progressive on rents; the other Moreover, a general hierarchically 5.0925 which a the most negative coefficient income tax. has two, 3 and 4, yields at statistically the .05 income and as is F-test between significant New its the two an F-ratio level. on of The state as well as substantively significant. V. The Amenity Orientation of Office Location Amenity factors appear 31 to predict rents much more are a number of good reasons for move to more we will considerations, with the most specific the should be explanations of why amenity factors general Beginning to be so. this there that argue We will factors. than do cost powerfully predictors. best A. Specifics of the Cost Model property problems. No matter how we view the question of and commercial tax between This rates. negative residential property tax coefficient, is anything, if measuring, the property tax tax rate for coefficients both the .05 at insignificant our to fourth is variable tax. the commercial amenity model. tax property level. leads us to property residential As a final test of colinearity, we added property fact, interpretation of the straightforward with the the commercial The explain. combined believe that what incidence, correlation .865 property residential to difficult a shows matrix correlation is relation negative the interpretive tax rate posed significant commercial this to attached coefficient negative The rates The became This convinced us that colinearity was the problem. The insignificance of consistent with other recent research gradient. on the theory, rents business district to compensate rent diminish as our distance coefficient theoretical In for the increased travel 32 empirical classical distance The decline grows. and from in rents is location the central is thought costs to the center city. A weakness of this (1) heroic assumptions: transport surface direction; (2) area district; (3) must and be a flat travel production take uniform throughout ever developments in in the areas model. to become the any in central a business and maintenance region. Although no assumptions, intra-metropolitan distribution plausibility of Suburbanization has caused metropolitan increasingly attraction exerted in distribution of economic activity especially weaken the the gravity rather undifferentiated approximated these the its equally costly and place been the costs of construction metropolitan area has recent has always There is making all metropolitan model multinuclear, by the core city. weakening the Empirical studies of urban land-value gradients over time show that the gravity model is losing predictive power. As a result of the dispersion of business activity and the growth of other centers, distance from the central business district once commanding metropolitan variation The is gradually losing its power to explain in site value. 2 6 dispersal of economic intra- activity throughout metropolitan New York lessens the need and thus the cost of travel to New York City. rent gradient, our distance B. All of which tends to flatten which may help explain the insignificance of coefficient. Amenities and Monopolistic Competition We have assumed that fixed, the while demand shifts a location. Implicit is in the short according supply is to the desirability the view that 33 run, the supply, of office is a homogeneous product distinct from the amenities space, of its location. not space to as Yet it is plausible to think of office but homogeneous, its of the amenities as according differentiated location. Many commodities are Just as differentiated by reputation, quality, or fashion. so from Macy's, suit the same commodity as a from Brooks Brothers is not a suit an as commodity Supply City. Jersey cannot not the same is Greenwich measured be simply in in since the product supplied has diverse quantities, physical in office competition monopolistic in an office qualities. the short In fixed under model. But run, competition, monopolistic this has rent differentials across for office space fixed the in should observe long-run time Jersey competition, there is seller in our consequences If we assume that towns. should supply rent in to control fixity. over between, rents lower is that to short-term addition a long-term level. demand, Yet, we for example, Why does supply not increase reason The In the to meet increase differentials Greenwich City? up rents. to an equilibrium fall Greenwich and Jersey City. over in long-term demand can bid short-run, rents and is is a homogeneous product, then with supply however, run, long it as the office-space market is characterized by if monopolistic competition, the supply of office stock is the the to level of monopolistic for fixity in supply, Product differentiation gives a 34 scarce resource -- the prestige for as people Insofar of the product. then location, the prestigious rent. long time command a higher are scarce profits resources, that their If suits are unique, Brothers Greenwich are a different change, for a and reputation then can convince people increasing the supply of not necessarily lower the price of a suit. scarce command higher rents can seller Prestige Brooks Brothers other-make suits will Brooks the owners can earn long-term and their from them. to pay more are willing Prestigious resources, office and locations their owners in can in the long term because they provide product. Eventually, new prestigious it is true, locations emerge. fashions Market power to raise prices diminishes. Our model determination and of a examines only cannot prove or short-term disprove monopolistically competitive since amenities are the basis our amenity- oriented model of rent the hypothesis office market. product Yet, differentiation, is at least consistent with the theory of monopolistic competition. C. Amenities and Office Location Theory Cost models of firm geographers (1956), such as Weber primarily to Manufacturing firms location respect factors with location were developed by (1909), Losch explain are to thought to the plant and 35 and Isard location. industrial to markets of production on the other. materials (1954), processed choose on the an one optimal hand and Because shipping raw commodities from the plant is expensive, sensitive make as difficult sense to functions "office location be fairly since costs of sensitive not it is office argues Malamud that to costs 2 7 of any location locational tradition and offices, to be less activities." economic to models do locational perceived is intangible, case of the Since the costs and thought decision-making. such as than are most in the measure is these cost-oriented Yet to costs. much location decisions are often are typically small made by fashion. can weigh There is no process of accounting that the enhancement in quality of executive decisionmaking in a given locatio 8 against the costs of operating at that location. In addition, the greater mobility of offices in with manufacturing comparison of choosing a poor are smaller Surveys decisions location. are of another window on than location that who make costs locational the determinants of office of alternative about hard financial the costs to the trendiness proximity to with "executives 2 9 data". of the crowd. executive 36 ideas The alternative or "swarming," that they are minimizing the by staying sites, on vague and personal decisions on uncertainty feel the Since little quantitative evidence is available must base location contribute that means locat-ion. executives on the costs and benefits rather plants very sites may as executives risks of choosing a poor 3 0 Many surveys residences is often reveal a key influence on location in International surveys also influence decisions to di sameni t ies Sydney, London, reveal and New York. that push move to the suburbs. include congestion, expansion, and high rents. In 3 1 factors These urban lack of room for a survey of major English- speaking na tions, only American executives mentioned a poor overall u rban environment This probably decisions. urban life in American, as a reflects factor the British, in relocation relative quality and Australian Th ere have been no good studies of 3 2 cities. of the influence of prestige on location decisions, even though real estate pla ce agents Surveys with of to great executives respect swarm a to a financial deal of find prestige 3 4 relocation. fashionable emphasis The institutions. may Banks may be favor 3 3 prestige. menti )ned tendency location on frequently for offices to reinforced conventional, prestigious sites when considering loans to developers. D. preference industrial widespread rather office-location than recognition cost decisions, calculation the like Malamud equilibrium models communication costs industrial evidence of the are endeavor for analogous personal characterizes of influential. create of Some neoclassical location to model. importance 37 to office location that equilibrium-cost models location theory remain highly researchers the 3 5 Offices and Household Location Theo ry Despite in by in which transportation costs Yet the subjective pervasive factors, in office-location the possibility of within the context of Given the centrality of personal preference in and prejudice, ignorance of alternatives throws decisions office-location model developing an industrial location theory. 3 6 office Traditional income industrial office location. theory assumed that moved the to the benefit of extra commuting.37 extra than a understanding location household households preferred context theoretical for theory location should offer location theory household location, satisfactory more on doubt considerable they because suburbs the costs of land more than by research recent But upper Wheaton indicates that extra land is actually valued less than the He concluded that the demand costs of commuting. does explain migration to not suggested that people are taxes and amenities, suburbs; the 3 8 quality. when tested local (i.e., received) services housing found location and evidence correlated with the local is by assuming taxes land and bidding up their that tax property net values the prices. are 3 9 quite similar Oates model to our model 38 fiscal and demand Oates positively expenditure and negatively rate. fiscal paid raising households, lower Oates then that between difference attract with local the location. residential hypothesis Tiebout's residuals for choosing he Tiebout was the first to argue that households examine advantages land instead, the suburbs by drawn to such as school for correlated of of office household location. Where he property residential found the same negative correlated with property value, we found correlation rents. with correlated significant findings with our The location. causal models and our office executives. offices to locate to VI. Not link What of office amenity model location model location household between is of these the consistency is office taxes 4 0 location. household for our purposes and theories and property found residential Reschovsky also negatively taxes property residential between negatively taxes is the preferences of surprisingly, corporate officials prefer like places where they reside or would in reside. Public Policy and Office A. Location A Role for Government? Before we implications of our turn to some of the public findings, we should examine the why should government intervene can be externalities. There is office issue: why not location, We believe that government let the market function freely? intervention in policy justified reason the on basis that to believe of although the costs to firms may not differ much across locations, the costs to society differ considerably. legitimate private costs locations. example. role in reducing and the Campus-style Built the social suburban divergence between the for costs office along major highways, 39 Government has a many sites these are office office a good parks of sewers, governments assume the costs local these and highway expansion to accomodate are major highway capacity is enormous -By the since costs firm, private The the to estimate costs transportation Manhattan, regional time to work is which throws cost travel much of of sites At rely the for is however, 1 use: disparity on auto use, while the 40 travel in reduction -- in energy energy relies use The the transportation double virtually is at achieved "The Manhattan in sites. executives Differences the subcenters, campus move to the suburbs. explain regional The at campus sites locations." 4 survey time (including most pronounced energy greater a locations suburban constant. time to work, Manhattan transport with relative magnitude of travel on why offices light energy use per employee that the to a campus site, but total remains time to work is reduced choose conducted office and subcenters, reduced, etc.) trips, travel A place. associated the among For firms moving from Manhattan lunch to incentive Plan Association Regional employees office as are not borne by the firm. campus site of in already costs the since subcenter regional no such fewer external creates is has increased subcenter, regional infrastructure however, Offices sites. and is borne by the public. and Bridgeport, Stamford, Newark, in a location contrast, utilities, cost of and the traffic generators, and state Typically, locations. very popular have become in the mode of use: on campus transit. per employee is halfway between the Manhattan Such dramatic contrasts social costs incurred encourage economic B. in energy low the campus energy use suggest by different office conservation, justification and some of the locations. government for regulating high. office To has a sound location. The Dilemmas of Office Development We can findings tell office now turn us about development in Our model to the do our to stimulate the outer boroughs? in the determination of what New York City's efforts indicated the assumed fixity question: that supply, rents. in costs the short run, had little About the due to bearing long-run on importance of costs, our model tells us nothing directly. Nonetheless, many geographers office location is be fashion and is monopolistically casts and development taxes in outer developers determining on other the in incentives boroughs of New there are implications enormous for differences 41 the long the office costs long-run of for would rents. run, tax York have a of abatements, Commercial for market All stimulating Westchester County, far prefer Westchester. grave if then efficacy The amenity orientation general, And even in to costs and seems to in the outer boroughs. are higher the amenity oriented. in even not very sensitive doubt subsidies, that competitive, secondary role this have concluded office property example, City, yet than office 4 2 of office location the outer boroughs. among within and has, in While boroughs, overall, the outer boroughs have socioeconomic profile --- executives Residential than in County.43 It Fairfield done about this. desirable say, of corporate Fairfield County. in the outer boroughs are York State, though lower higher than is not clear, however, what can be With the preponderance of apartments New York City, benefit does, property taxes New less from the perspective than suburban a much lowering landlords, residential property but not necessarily taxes in would tenants. Quite simply, the poverty, blight and crime of many parts and of the outer -- Brooklyn boroughs -- are a state the resources required New York City; afford both promise if and to create the federal the our cities. formidible Moreover, development. local to office governments government, and the Bronx obstacle a decent military budget The outer especially environment meanwhile, the lack in cannot reconstruction of boroughs would appear to have more costs were the key determinant of office location, for New York City is in a much better position to reduce development attractive costs than to make the outer places to live Our development findings in boroughs and work. pose a number of dilemmas for office the outer boroughs. First, if executives will tend to prefer the amenities of the suburbs, then back-office development may offer for routine the most functions promise involve 42 few the outer executives. boroughs, since Unfortunately, back-office functions technologies, growth. and are the most thus offer rapidly replaced by new little potential employment So the very office functions the boroughs are most likely to obtain, likely to local are the office functions that are least enhance employment opportunity and stimulate borough explicitly economies. 4 Swedish government back-office jobs to depressed regions precisely because it was thought these in The the 1960s not to relocate that decided 4 jobs would be replaced by automation. Instead, the Swedes chose to relocate headquarter functions to those 5 regions. 4 Second, if amenities are in fact crucial, then some boroughs have more promise than other locations in locations. income and Bronx. a given Staten a lower borough Island and more promise Queens unemployment Because of boroughs, rate this amenity have a and some than higher than Brooklyn comparative other median and the advantage, Queens and Staten Island may hold more potential for office location and likely variety the than Brooklyn or the Bronx. Bronx transit of potential Similarly, to locations the rest for office of the city; designated as an office park, in the very poor a itself transit access. from the least within boroughs there are development. the Fordham Road business district links it is Brooklyn that most need new jobs, and appear to get them. the Bronx, Yet physical If and 43 In has excellent Baychester Commons, northern Bronx has firm desires social a disamenities to isolate of a borough downtown, city is, in the firm may prefer fact, Of development. marketing course, an office park. these precisely office because The parks the office for parks are isolated from the disamenities of borough downtowns and lack transit facilities, lower-income borough they are all but residents. A key characteristic lower-income New Yorkers jobs created in office parks would suburban inaccessible to of is that they do not own cars, and almost certainly go to commuters. All of determinants, this such suggests as that executive market locational preferences, not will necessarily reduce employment disparities between Manhattan and the outer Yorkers. boroughs, Office preferable to first, the jobs in and city of second, for borough location in office parks infrastructure The provide development because downtown jobs income people; by or poor downtowns for two development must be provided fact that the city has good to low- the external in costs office parks -- -- borne where could be substantial. reasons to regulate office location, however, by no means implies that it will. so many alternative locations other jurisdictions, regulate office suburbs. If it available to With developers in the city fears that any attempt to location will is to reduce employment and income within be able exercise to is reasons: are more accessible because New land-use 44 only lose the growing offices the disparities of New York City, controls to to the city must divert office development from Manhattan Yet the exercise boroughs. is the dilemma -C. What Is in boroughs. for genuine attracted, the of those controls of public vexing attract offices policy As to the outer any, development. in the outer for will How be we saw, efforts boroughs hold office simply little promise The is office is not likely residents jobs jobs; and least economic in need development to provide of those jobs boroughs? of New York City to use land-use to divert to to developers are satisfactory New development low-growth back-office boroughs that the unemployed ability and here the suburbs. by office development. sites most attractive of -- must be to extricate dilemmas posed economic if of the outer To Be Done? York from the outer parts might only chase offices to The task the to distressed controls Yet the and taxes growth from Manhattan to the distressed downtowns of the outer boroughs is undermined by the myriad political boundaries. spans over portions of The New York metropolitan three states and a dozen suburban counties. income taxes; Firms that every town Each state levies economy includes more than levies different different property need access to Manhattan can locate outside taxes. of New York City, or even outside of New York State, and incur lower taxes and cheaper land. 4 and congested permanent office Manhattan gridlock), employment 6 becomes no matter becomes 45 (83 So no matter how overbuilt (east Midtown how unevenly percent of total is in near- distributed New York City office regulate space office is in 4 7 Manhattan location without ), the fearing city cannot the erosion of its tax base. What fewer fiscal office reason is there to believe, however, that jurisdictions would enable the growth to the outer boroughs? experiments are not possible meteorology or of astronomy, London approximates in Although controlled the social for that City to divert sciences matter), crowding such a control. Council, however, London: the has As new congestion. jurisdiction office Controls were construction 1964 and 1977 an estimated in least in Regional enable part, to the Council is revenue sharing fiscal tax base. disparities that development in does not London. Between to the jobs suburbs, of owing, 4 8 controls. a would location wtihout fear of Greater New York government, can help City through reduce encourage the suburbanization Only a reduction of metropolitan possible then, tax jurisdiction the federal and grants-in-aid, households and offices. balkanization While not imminent, metropolitan introduced in 1964 to imposition New York to regulate office its London 170,000 to 250,000 office government and a unified eroding Greater all central were dispersed from the center city at The over in New York, London with its suburbanization of offices, erode the tax base. limit and in New York will the distressed 46 in the experience office space expanded enormously in central concommitent (nor the of the political make business office districts of the outer boroughs. 47 TABLE 1: Data Matrix for Selected Variables # Town Name 1. 2. 3. Bridgeport Danbury Darien 4. 5. 6. 7. Westport Greenwich Stamford New Haven 8. 9. 1981 Mean Rent (per sq.ft) 1980 Pop. (in thousands) 1980 Median Income (in thousands) $16.168 18.045 20.500 142.546 60.470 18.892 $ 6.081 7.957 18.153 22.415 26.612 27.331 15.963 25.290 59.578 102.453 126.109 16.925 16.602 10.719 5.822 Englewood Cliffs 17.462 19.078 Fort Lee 5.698 32.449 14.535 13.295 10. Hackensack 11. Montvale 17.689 15.863 36.039 7.318 9.462 10.814 12. 13. 14. 15. 15.385 16.000 12.500 14.871 26.474 19.068 11.407 5.330 9.692 9.199 10.792 11.681 16. Newark 17. West Orange 14.511 15.202 329.248 39.510 4.525 10.837 18. Jersey City 19. Secaucus 14.146 15.000 223.532 13.719 5.812 9.495 20. Lawrenceville 21. Princeton 22. New Brunswick 10.000 14.810 12.591 2.109 12.035 41.442 12.479 9.502 5.782 23. Piscataway 24. Woodbridge 25. Freehold 14.090 16.987 10.000 45.555 13.762 10.020 7.143 10.483 6.957 26. Red Bank 11.222 12.031 8.344 27. 28. 29. 30. 31. 32. 33. 34. 35. 14.357 15.792 14.596 13.000 16.595 14.752 14.730 14.000 12.064 9.359 16.614 5.305 7.465 11.983 9.710 106.201 7.118 55.593 9.528 9.254 10.492 4.900 10.693 9.000 6.712 11.571 5.625 36. Garden City 37. Great Neck 15.241 14.288 22.927 9.168 13.602 13.209 38. 39. 40. 41. 42. 43. 44. 45. 46. Lake Success Hempstead Hauppauge Melville Elmsford Rye New Rochelle Scarsdale White Plains 18.459 10.500 11.839 13.897 10.631 19.500 22.000 14.961 17.153 2.396 40.404 20.960 8.139 3.361 15.083 70.794 17.650 46.999 22.495 7.236 8.149 9.843 9.603 14.756 10.343 22.956 10.876 47. Tarrytown 15.890 10.648 10.778 Paramus Rutherford West Caldwell Roseland Florham Park Morristown Parsippany Toms River Bridgewater Franklin Twp. Elizabeth Springfield Union 48 TABLE 1(cont.) # Town Name Mean Stories 1. Bridgeport Danbury 11.000 3.833 Darien Westport Greenwi.ch Stamford New Haven 3.000 3.000 3.100 5.852 10.333 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. Englewood Cliffs 2.667 Fort Lee Hackensack Montvale Paramus 6.636 6.000 1.750 3.571 Rutherford 12.000 15. 16. 17. West Caldwell Roseland Newark West Orange 2.000 3.714 16.788 3.500 18. Jersey City 12.500 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. Secaucus Lawrenceville Princeton New Brunswick 4.667 2.000 2.688 6.500 Piscataway Woodbridge Freehold 2.600 5.111 5.000 Red Bank Florham Park Morristown 3.500 2.400 5.286 Parsippany Toms River Bridgewater Franklin Twp. Elizabeth Springfield Union Garden City 3.000 3.000 3.500 3.500 6.000 3.000 2.667 4.333 Great Neck Lake Success Hempstead 3.545 3.000 7.000 Hauppauge Melville Elmsford 3.333 3.538 4.000 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 24. 25. 26. 27. 28. 29. 30. 31. 32. 33. 34. 35. 36. 37. 38. 39. 40. 41. 42. 43. 44. 45. 46. 47. Rye New Rochelle 2.000 17.000 Scarsdale 4.333 White Plains Tarrytown 6.882 6.000 49 Commercial Prop. Tax Resi- dential Prop. Tax $2.86 1.15 1.36 $2.06 2.29 1.39 .95 1.60 3.81 1.05 1.69 2.64 1.69 1.62 2.24 2.52 0.85 1.71 3.95 1.47 1.82 2.85 1.71 2.13 3.18 2.86 4.40 6.46 3.50 6.88 3.88 3.12 2.17 4.67 2.96 3.23 1.58 1.11 586 2501 1465 421 1560 915 707 237 4647 1.81 2.09 2.72 2.73 1.46 2.48 1.85 1.91 1.79 2.18 3.00 1.83 1.80 3.34 3.63 3.28 3.70 3.83 3.32 3.77 3.04 3.50 4.44 2.54 3.51 3.60 2.74 4.00 3.43 1.53 6.65 5.50 5.04 6.36 4.16 4.30 5.78 5.20 8.30 6.80 4.60 5.50 3104 3.56 3.07 4.25 1.70 1.86 1.73 2.59 1.99 3.71 2.25 3216 1564 1994 2551 4621 5513 3.12 2.28 2.90 2.50 # of Mgrs. 2117 4948 372 69 405 840 1310 708 337 473 446 624 246 279 505 255 2548 616 1187 2049 717 290 1322 480 320 172 1263 4294 2026 3165 501 Table l(cont.) *Sources: Mean Rent - Black's Guide 1982 Stories - Black's Guide 1982 Comm. Tax - Center for Local Tax Research Res. Tax - Center for Local Tax Research Income - U.S. Bureau of the Census 1983 Population - U.S. Bureau of the Census 1983 Managers - U.S. Bureau of the Census 1972 50 Table 2a: 1982 Utility Cost Differentials in the Region* KWHR STATE UTILITY 1,500 10,000 150,000 N.Y. Con Edison LILCO $ 299 170 $1,402 1,091 $19,540 14,527 N.J. Jersey Central Power & Light PSE&G 171 864 12,274 183 930 12,254 United Illuminating Conn. Light & Power 208 193 192 1,111 14,962 11,256 11,227 CONN. Hartford Electric Light *Source: Edison Electric TABLE 2b: (1) Corporate 1981 978 976 Institute Income Tax Differentials Income: State Flat Rate New York 10% No 9% No 10% No New Jersey Connecticut (2) Personal Federally Deductible? Income: New York: 2% up to $1,000 and New Jersey: Connecticut: *Source: in the Reqion* The Tax 14% 2% up to $20,000 and above $23,000 2.5% 7% on capital gains. above $20,000 Foundation, 51 Inc. above 20,000 1-9% on dividends TABLE 3: 1. 1980 Office Building Operating Expenditures* The components of office operating expenditures: Energy Cleaning Real Estate General Building Costs Administrative Costs Other 2. Downtown New York and other major downtown sites 1980, in Total New York Tulsa San Francisco Houston Washington, D.C. Atlanta Differentials suburbs for sq. ft): in selected operating regions Region Middle Atlantic Northern Midwest Southern Southwest Expense 985.6 760.3 543.2 533.9 506.0 491.6 423.1 Chicago *Source: (for cents per sq.ft): City 3. 22% 15% 22% 10% 6% 25% City 833.4 502 443 481 expenses in cities (for 1980, in cents Suburbs 605.3 516 406 487 Building Owners and Managers Association 52 vs. per TABLE 4: Correlation Matrix For Selected Variables* Mean Rent Distance Mean-Rent Distance 1.000 Stories -0.038 1.000 0.123 -0.141 1.000 Comm. Tax -0.223 -0.297 0.506 1.000 Electricity -0.036 -0.071 0.221 0.666 1.000 Res. Tax -0.338 -0.170 0.399 0.865 0.609 1.000 Income 0.450 -0.189 -0.365 0.023 0.212 -0.055 1.000 Population 0.120 -0.051 0.740 0.279 -0.066 0.280 -0.409 1.000 Managers 0.598 -0.068 0.624 0.176 0.053 0.117 -0.035 0.755 Clerical 0.114 -0.127 0.732 0.296 -0.069 Stories *Sources: Comm. Tax Electricity Res. Tax Income Population 0.303 -0.413 Managers Clerical 1.000 0.971 0.769 Mean Rent - Black's Guide 1982 Distance - Regional Plan Association, Map of Region Stories - Black's Guide 1932 Comn. Tax - Center for Local Tax Research Electricity - Edison Electric Institute Res. Tax - Center for Local Tax Research Income - U.S. Bureau of the Census 1983 Population - U.S. Bureau of the Census 1983 Managers - U.S. Bureau of the Census 1972 Clerical - U.S. Bureau of the Census 1972 53 1.000 TABLE 5: Derivation of Dependent Variable and Its Variance Derivation of weighted mean rent: Let ri = rent/sq.ft in building j, town i. Assume rij has a constant variance: ( )2 Now, mean rent in town i, is given by: ri= ni E rij Si j=l = total rent in i total sq.ft. in i ni =sij j=l where si- is the sq.ft for building ni = num er of buildings in town i. j in town i Derivation of variance of mean rents: nThen, variance (ri) 12 E si* j=1 n1 = var(rij) 2 n= ( G2) ,=12 Therefore, weighted least squares is the appropriate technique. Assuming rents have a constant variance across towns, observed mean rents will be heteroskedastic, as demonstrated in the derivation above. 54 Notes 1. An Urban and P.W. Daniels, Office Location: 1975), p. 1. Bell, Study (London: 2. on the New Samuel M. Ehrenhalt, "Some Perspectives York City Economy in a Time of Change," in New York City's Changing Economic Base ed. Benjamin J. Klebaner (New York: Pica Press, 1981), p. 13. 3. Ibid., 4. Regina B. Armstrong, "National Trends in Office Construction, Employment and Headquarter Location in Patterns of Office U.S. Metropolitan Areas" in Spatial John Growth and Location, ed. P.W. Daniels (New York: Wiley and Sons, 1979), p. 64. 5. Office Ian Alexander, York: Longman, Inc., 6. Armstrong, "National Trends in Office Construction, Headquarter Location in Employment and Metropolitan Areas," p. 86. Regional p. 18. Location and Public 1979), p. 40. Policy (New U.S. 88. 7. Ibid., p. 8. "New York City and the Jr., Thomas M. Stanback, Changing Services Transformation" in New York City's Economic Base ed. Benjamin J. Klebaner (New York: Pica Press, 1981), p. 53. 9. Ehrenhalt, Economy in 10. Elizabeth Dickson, "Changing Commuting Patterns to New York City," New York City Office of Economic Development, 1982. 11. Gail G. City, 1960-1975," on the New York City "Some Perspectives a Time of Change," p. 15. Schwartz,, "The Office Pattern in New York Spatial Patterns of Office Growth (New York: P .W. Daniels John Wiley in and Location, ed. and Sons, 1979), p. 229. 12. See, for example, Regina B. Armstrong, The Office Industry: Patterns of Growth and Location (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1972), p. 2. 13. Schwartz, "The Office 1975," pp. 224-227. 14. Cited p. in Alexander, Pattern Office 8. 55 in New Location York and City, 1960- Public Policy, 15. P.W. Daniels, on Office Location "Perspectives Research," in Spatial Patterns of Office Growth and Location ed. P.W. Daniels (New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1979), p. 23; and Alexander, Office Location Public Policy, p. 25. 16. Alexander, Office Location and Public 17. Such a tax was imposed in Paris, Policy, p. 54. see Alexander, pp. 76-78. 18. Ibid., p. 19. Schwartz, "The 1975," p. 226. 20. Ibid., p. 215. 21. Ibid., p. 221. 22. See "Black's Guide 82: Space Market," published Bank, New Jersey, 1982. 23. According to William C. Wheaton, this developers. thumb among office 24. William 25. James Heilbrun, Urban Economics and Public York: St. Martin's Press, 198 1), p. 461. 26. Ibid., 27. Cited in Daniels, Research," p. 4. 28. Ibid., 29. Alexander, Office Location and Public Policy, 30. Ibid., p. 52. 31. Ibid., p. 52. 32. Ibid., p. 48. 33. Daniels, p. 14. 34. Alexander, Office Location and Public 50. Office Pattern in New York City, 1960- Suburban Manhattan Office by James F. Black, Jr., Red is a rule of C. Wheaton,' "The Incidence of InterJurisdictional Differences in Commercial Property Taxes" (December 1981), p. 3. Policy (New p. 148. "Perspectives on Office Location p. 4. "Perspectives 56 on Office Location p 18. Research," Policy, p. 50. 35. Daniels, p. "Perspectives on Office Location Research," 15. p. 4. 36. Ibid., 37. "Impacts of the New Federalism on Michael Wasylenko, Location of Households and the Intra-Metropolitan A Review of the Evidence on Intra-Metropolitan Firms: TRED at presentation Location" (paper prepared for Conferences, 1982), p. 23. 38. An AnalyW.C. Wheaton, "Income and Urban Residence: Location," American Ecosis of Consumer Demand for pp. 620-631. nomic Review 67(1977), 39. Taxes and Local of Property W.E. Oates, "The Effects An Empirical Values: Spending on Property Public Tiebout and the Tax Capitalization of Study Economy 77 (1969), Hypothesis," Journal of Political pp. 957-970. 40. A. Reschovsky, "Residential Choice and the Local PubAn Alternative Test of the Tiebout Hypolic Sector: thesis," Journa L of Urban Economics 6 (1979), pp. 501- 520. 41. "Travel CCumella, Robert and Pushkarev Boris Office Building Settings," Requirements of Alternative Plan Association, Technical Report No. 2, Regional 1983. 42. Center for Local Tax Research, "Effective Real Property Tax Rates in the Metropolitan Area of New York," 1981, pp. 9-12. 43. Ibid., 44. Daniels, p. pp. 9-12. "Perspectives on Office Location Research," 16. Office 45. Alexander, 46. Schwartz, "The 1975," p. 216. p. 218. 47. Ibid., 48. Alexander, Location Office Office Pattern Location 57 and Public in Policy, New York and Public p. City, Policy, p. 78. 1960- 65. Bibliography Alexander, Ian. Office Location York: Longman Inc., 1979. and Policy, Public New Alonso, William. "Location Theory," in Regional Policy, The Cambridge, MA: eds. John Friedman and William Alonso. MIT Press, 1975. Armstrong, Regina B. "National Trends in Office Construction, Employmen t and Headquarter Location in U.S. Metropol itan Areas," in Spatial Patterns of Office Growth New York: and Location, ed. P.W. Daniels. John Wiley and Sons, 1979. Armstrong, Regina B. The Office Industry: Patterns of Growth and Location, Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1972. Black's Guide 82: Published by James Suburban Manhattan Office Space Market. F. Black, Jr., Red Bank, New Jersey, 1982. Owners and Building "Experience and Exchange Managers Association Report, 1981." (BOMA). Carlton, Dennis W. "Why Do Firms Locate Where They Do: An Economet ric Model," in Interregional Movements and Regional Growth, ed. Williaii C. Wheton. Washington, D.C.: The Urban Institute, 1979. "Effective Real Property Center For Local Tax Research. Tax Rates in the Metropolitan Area of New York," Nov. 1979, Nov. 1981. Commerce Clearing Taxes," 1982. Daniels, in Spatial Daniels. Daniels, Study. House, Inc. "1982 Guidebook to New York P.W. "Perspectives on Office Location Research," Patterns of Office Growth and Location, ed. P.W. New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1979. P.W. London: Office Location: Bell, An Urban and .Regional 1975. Edison Electric Institute. cial and Industrial Bills Winter 1982. Commer"Typical Residential, - Investor-Owned Utilities," Ehrenhalt, Samuel M. "Some Perspectives City Economy in a Time of Change," in Changing Economic Base, ed. Benjamin J. York: Pica Press, 1981. 58 on the New York New York City's Klebaner. New "Office Development and Urban and Regional Goddard, J.B. of Office Patterns Spatial in Development in Britain," John New York: Daniels. P.W. ed. Growth and Location, Wiley and Sons, 1979. Heilbrun, York: St. Urban Economics James. Martin's Press, 1981. and Public Policy. New Taxes and Local of Property "The Effects W.E. Oates, An Empirical Study of Public Spending on Property Values: Tax Capitalization and the Tiebout Hypothesis," Journal of Economy 77, 1969. Political Pushkarev, Alternative 2, Regional R, "Travel Requirements of B. and Cumella, Office Building Settings," Technical Report No. Plan Association, 1983. Choice and the Local Public "Residential Reschovsky, A. Test of the Tiebout Hypothesis," An Alternative Sector: Journal of Urban Economics 6, 1979. Schwartz, Gail. "The Office Pattern in New York City, 196075," in Spatial Patterns of Office Growth and Location, ed. John Wiley and Sons, 1979. New York: P.W. Daniels. "New York City and the Services Stanback, Thomas M., Jr. New York City's Changing Economic Base, Transformation," in Pica Press, 1981. New York: ed. Benjamin J. Klebaner. of New Jersey. State Taxation of the Dept. of 1981." The Tax Foundation, "Annual Report of the Division the Fiscal of the Treasury for Inc. of Year "Facts and Figures on Government Finance," 1981. 1980 Census of Population and of Commerce. U.S. Dept. Summary Characteristics for Governmental Units and Housing: New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, 1982. SMSAs: 1980 Census of Population, General of Commerce. Dept. U.S. New York, New Jersey, Population Characteristics: Connecticut, 1982. U.S. Dept. of Commerce. Population Characteristics: ticut, 1972. 1970 Census of Population, General New York, New Jersey, Connec- 1977 Census U.S. Dept. of Commerce. Compendium of Government Finances, 1979. 59 of Governments: "Impacts of the New Federalism on the Wasylenko, Michael. A Location of Households and Firms: Intra-Metropolitan Review of the Evidence on Intra-Metropolitan Location" at TRED Conferences, (Paper prepared for presentation 1982). "Income William C. Wheaton, Analysis of Consumer Demand Economic Review, 67, 1977. An and Urban Residence: for Location," American Wheaton, William C. "The Incidence of Inter-Jurisdictional Taxes" (unpublished in Commercial Property Differences working paper, Department of Economics, MIT), December 1981. 60