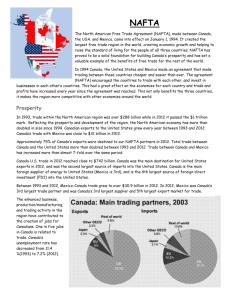

Lessons from NAFTA: The Case of Mexico's Agricultural Sector

advertisement